JUPITER: Mozart in the Drawing Room

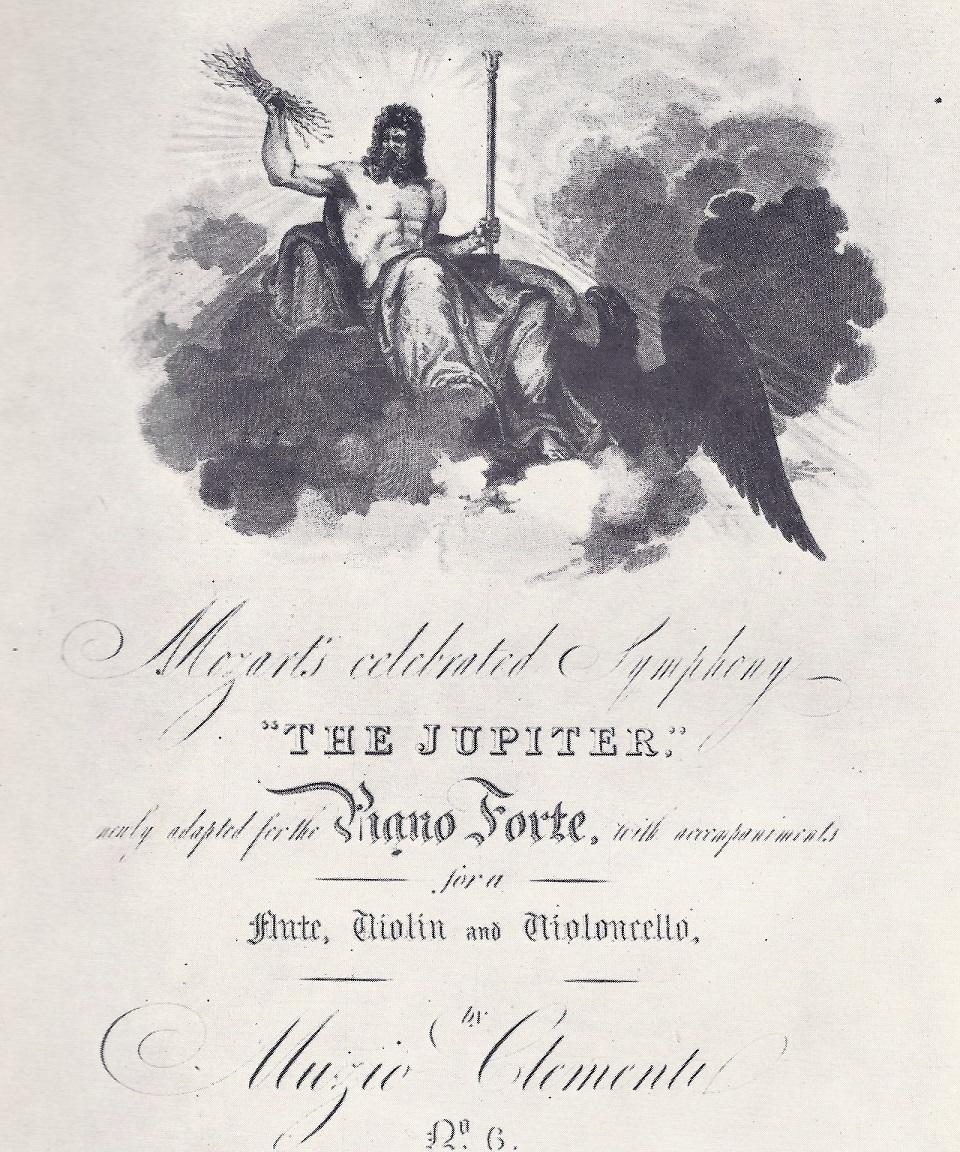

How did people hear Mozart's large-scale compositions for orchestra up to c1850? The very fortunate may have heard his late symphonies in large metropolitan centres, or have experienced his piano concertos in the hands of a renowned soloist. But there was a significant tradition - centred on London - of arranging Mozart's symphonies, concertos and overtures for an ensemble (the 'JUPITER' ensemble) consisting of fortepiano, flute, violin and cello. The JUPITER project examines the cultural role of the music of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and their contemporaries in the context of the early 19th-century British country house. It does this first by recovering the forms in which symphonies and concertos from the last third of the eighteenth and first third of the nineteenth centuries: in arrangements for fortepiano, flute, violin, and cello. The project reconstructed these versions of such well-known works as Mozart’s JUPITER Symphony on a recording for Hyperion Records, and investigated the context for these arrangement within early 19th-century drawing room and regency listening practices in a video made at Chawton House, Hampshire.

Research

The underpinning research for this project focuses on repertory, performance practice, textual editing and analysis, performing spaces and habits of listening. The project started with research designed to be published in Mark Everist’s Mozart’s Ghosts: Haunting the Halls of Musical Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), but for which there was ultimately no place in the volume.

It was however recognised that the JUPITER ensemble of fortepiano, flute, violin and cello (1) dominated the British reception of the so-called Viennese classics (Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven) from the 1820s onwards and (2) played a key role in the domestic spaces with which the Sound Heritage project occupies itself. The first step was the establishment of a handlist of publications for this repertory; while this work is ongoing, the handlist is downloadable here. The second step was an analysis of the existing modern editions of JUPITER arrangements and currently available recordings. This formed the basis for a grant application to the Arts and Humanities Research Council of Great Britain which was awarded in September 2017. The award permitted the generation of performance materials for three works by Mozart in JUPITER arrangements. This material and analysis of the techniques of adaptation served as the basis for public performances and workshops in the summers of 2017 and 2018, the recording for Hyperion Records, and the video exploring listening habits and practices (described below). The underpinning research was also presented at a conference ‘Rethinking Musical Transcription and Arrangement’, at the University of Cambridge in May 2018.

It was however recognised that the JUPITER ensemble of fortepiano, flute, violin and cello (1) dominated the British reception of the so-called Viennese classics (Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven) from the 1820s onwards and (2) played a key role in the domestic spaces with which the Sound Heritage project occupies itself. The first step was the establishment of a handlist of publications for this repertory; while this work is ongoing, the handlist is downloadable here. The second step was an analysis of the existing modern editions of JUPITER arrangements and currently available recordings. This formed the basis for a grant application to the Arts and Humanities Research Council of Great Britain which was awarded in September 2017. The award permitted the generation of performance materials for three works by Mozart in JUPITER arrangements. This material and analysis of the techniques of adaptation served as the basis for public performances and workshops in the summers of 2017 and 2018, the recording for Hyperion Records, and the video exploring listening habits and practices (described below). The underpinning research was also presented at a conference ‘Rethinking Musical Transcription and Arrangement’, at the University of Cambridge in May 2018.

Performing

The recording includes the 1836 Munich version of the Piano Concerto in C major, K. 467, arranged by Johann Baptist Cramer; the Symphony No. 41, K. 551, arranged by Muzio Clementi; and the Overtures to Le nozze di Figaro (K. 492) and Die Zauberflöte (K. 620) arranged by Johann Nepomuk Hummel. Cramer’s earlier London JUPITER arrangement of the Mozart piano concerto is also recorded as part of the project and is available for download on the Hyperion Records website.

The team for the recording (and the instruments on which they played) included:

The team for the recording (and the instruments on which they played) included:

- David Owen Norris (fortepiano, copy of 1826 Broadwood by Christopher Barlow)

- Caroline Balding (violin, c. 1690 Steiner School; bow c.1780 Dodd)

- Katy Bircher (8 keyed flute after Heinrich Grenser, made by Rudolf Tutz)

- Andrew Skidmore (cello by Mathias Thir, Vienna, c. 1770; bow by Dodd, London, late 18th century)

- Philip Hobbs (sound engineer and producer)

- Christopher Barlow (fortepiano maker, engineer and tuner)

- Mark Everist (project director)

‘The JUPITER Project: Mozart in the Nineteenth-Century Drawing Room’ was released by Hyperion in August 2019. CDA68234. David Owen Norris was interviewed by the New York Times about the recording for publication on 19 July 2019: ‘Who Played Mozart When He was New?’

Listening

The JUPITER video, filmed at Chawton House, recreates a fragment of a musical event,

The JUPITER video, filmed at Chawton House, recreates a fragment of a musical event, based on the arrangements that are formally presented on the Hyperion recording. Objectives were to recreate an appropriate physical space, perform appropriate versions of the music (the JUPITER arrangements), and to display early nineteenth-century habits of attentive, inattentive and engaged listening.

based on the arrangements that are formally presented on the Hyperion recording. Objectives were to recreate an appropriate physical space, perform appropriate versions of the music (the JUPITER arrangements), and to display early nineteenth-century habits of attentive, inattentive and engaged listening.

Johann-Baptist Cramer dedicated his JUPITER arrangement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto in C major K. 467 to Sophia Greatreed of Landford Lodge, Wiltshire in May 1827. Almost certainly a 21st birthday present for the woman who might have been his pupil, the arrangement gives pointers to the type of space for which the arrangement might have been envisaged. A Grade II-listed building since 1960, Landford Lodge was built in the late eighteenth century, and most of the early nineteenth -century interior was assembled by the Greatheed family just before and during Sophia’s youth. Although it boasts four reception rooms and ten bedrooms, the reception rooms are modest, and give an intriguing context to Cramer’s arrangement. The largest room in the building is what is today called the drawing room and measures 8.04m x 5.88m; this would seat between eight or ten in addition to the four musicians and the instrument, bearing in mind that the room would not be set up with an audience in rows, but as a conventional drawing room of the period, with attendees grouped around tables, and other pieces of furniture.

Johann-Baptist Cramer dedicated his JUPITER arrangement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto in C major K. 467 to Sophia Greatreed of Landford Lodge, Wiltshire in May 1827. Almost certainly a 21st birthday present for the woman who might have been his pupil, the arrangement gives pointers to the type of space for which the arrangement might have been envisaged. A Grade II-listed building since 1960, Landford Lodge was built in the late eighteenth century, and most of the early nineteenth -century interior was assembled by the Greatheed family just before and during Sophia’s youth. Although it boasts four reception rooms and ten bedrooms, the reception rooms are modest, and give an intriguing context to Cramer’s arrangement. The largest room in the building is what is today called the drawing room and measures 8.04m x 5.88m; this would seat between eight or ten in addition to the four musicians and the instrument, bearing in mind that the room would not be set up with an audience in rows, but as a conventional drawing room of the period, with attendees grouped around tables, and other pieces of furniture.

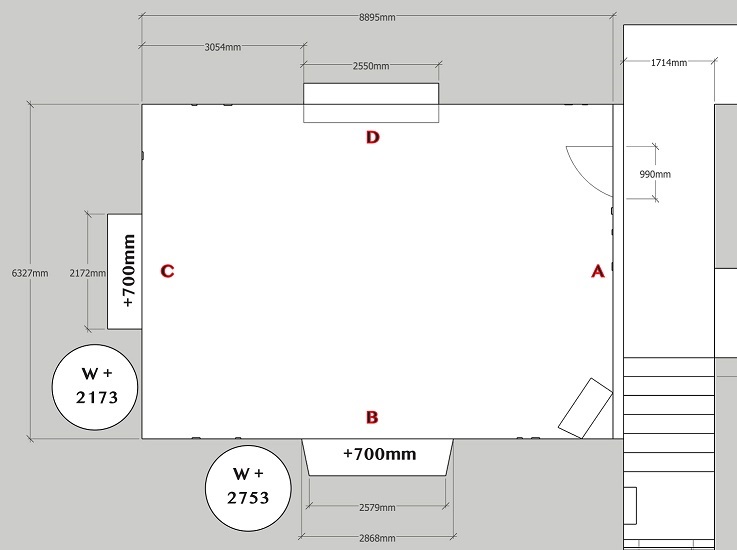

This reconstruction of Landford Lodge was the basis for the selection of the current dining room at Chawton House for the video setting. The relevant parts of the ground plans shows that the Chawton space is 8.80m x 6.20m (10% longer than Landford, and 5% broader).

The position of the fireplace is identical. While the position of the windows (a result of the Landford space having a single exterior wall and the Chawton one having two) is different, for the purposes of the musical event on video, this mattered little since the event was considered to have happened after dark, and enhanced by firelight (identically placed in both rooms). The ensemble were placed in the top right corner of the plan for the Chawton arrangement, and this might also have worked well for the Landford one as well, although the presence of the second door might also have suggested placing the ensemble top or bottom.

The position of the fireplace is identical. While the position of the windows (a result of the Landford space having a single exterior wall and the Chawton one having two) is different, for the purposes of the musical event on video, this mattered little since the event was considered to have happened after dark, and enhanced by firelight (identically placed in both rooms). The ensemble were placed in the top right corner of the plan for the Chawton arrangement, and this might also have worked well for the Landford one as well, although the presence of the second door might also have suggested placing the ensemble top or bottom.

While the arrangements of the music are the same as those recorded on the Hyperion CD, the circumstances of its performance and reception were depicted on the video in radically different ways. The space was furnished with items from the Chawton collection so as to created six different spaces: a reading table, a game of chess, a tea table, a game of cards, a sofa, and the space for the ensemble. These spaces were populated by members of the Hampshire Regency Dancers (HRD), an organisation that has worked on dance and other scenes for BBC and other costume dramas. A preliminary seminar was held at the University of Southampton in November 2018 when the project was explained to the HRD, examples of the music were performed, and differences between attentive, inattentive and engaged listening were presented.

The video consists of extracts from the first two movements of Cramer’s arrangement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto in C major K. 467 and the overture to Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte K. 620. Superimposed on these three extracts are activities that constitute attentive listening (the same way in which audiences are now encouraged to listen, although in the JUPITER context, this allows for gentle bodily movement that would be frowned upon today), inattentive listening and engaged listening. Inattentive listening or hearing is in evidence throughout the video: the audience engages in other activities while hearing the music. The video also gives two moments of engaged listening, where the audience contributes to the sonic world of the event. In the first, one of the participants leaps up at the end of David Owen Norris’ Eingang (a short cadenza) at the beginning of his first solo in the concerto, and asks him to play it again. Norris obliges with an extended cadenza which results in smiles and some eye-rolling from his colleagues, as well as the obvious delight from his listener who interrupted. And at the end of the video, the participants cannot wait for the reverential silence at the end of the Mozart Zauberflöte overture and cover the final cadences with applause.

The video consists of extracts from the first two movements of Cramer’s arrangement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto in C major K. 467 and the overture to Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte K. 620. Superimposed on these three extracts are activities that constitute attentive listening (the same way in which audiences are now encouraged to listen, although in the JUPITER context, this allows for gentle bodily movement that would be frowned upon today), inattentive listening and engaged listening. Inattentive listening or hearing is in evidence throughout the video: the audience engages in other activities while hearing the music. The video also gives two moments of engaged listening, where the audience contributes to the sonic world of the event. In the first, one of the participants leaps up at the end of David Owen Norris’ Eingang (a short cadenza) at the beginning of his first solo in the concerto, and asks him to play it again. Norris obliges with an extended cadenza which results in smiles and some eye-rolling from his colleagues, as well as the obvious delight from his listener who interrupted. And at the end of the video, the participants cannot wait for the reverential silence at the end of the Mozart Zauberflöte overture and cover the final cadences with applause.