Harpsichords at Mottisfont Abbey

THE HOUSE

Mottisfont Abbey is a country estate set in the Test Valley in Hampshire. The historic property at its centre was founded as an Augustinian priory in 1200 but has sustained a great deal of remodelling in its long life. It was following the dissolution of the monasteries, when Henry VIII gave the abbey to William, 1st Lord Sandys, that the property became a country home. This project concentrates on the house’s final major restructure, beginning in 1934, when the Russell family moved in.

Maud and Gilbert Russell and their two sons, Martin and Raymond, were the last family to treat Mottisfont as home. Maud gifted the estate to the National Trust in 1957, finally moving out herself in 1972. As far as possible, it is through their eyes, most particularly Maud’s, that the National Trust visitor views the property today. Maud was a well-known patron and lover of the arts, and through her vision and drive Mottisfont became the home of a fashionable and influential artistic circle. Artists, musicians and writers came for long weekend parties and were inspired by Mottisfont’s past to make works for its future. Maud’s friend Derek Hill later left a significant collection of early 20th-century art to Mottisfont, including works by Degas, Seurat, Bonnard, Sutherland and Nicholson.

THE RUSSELL FAMILY AND MUSIC

Maud's children grew up with a firm sense of the value and importance of the arts, and it is from the activities of her youngest son Raymond that our project emerges. Raymond Russell (1922-1964) - a talented musician - was an avid collector and, despite his tragically short life, managed to amass one of the world’s most important and influential collections of historic keyboard instruments. Although much of his childhood and early adulthood was spent in education and military service away from home, Raymond kept keyboard instruments at Mottisfont: a Dolmetsch harpsichord and clavichord, and possibly a Pleyel harpsichord that he undoubtedly owned. Until recently there were few clues to this musical heritage at Mottisfont.

Maud's children grew up with a firm sense of the value and importance of the arts, and it is from the activities of her youngest son Raymond that our project emerges. Raymond Russell (1922-1964) - a talented musician - was an avid collector and, despite his tragically short life, managed to amass one of the world’s most important and influential collections of historic keyboard instruments. Although much of his childhood and early adulthood was spent in education and military service away from home, Raymond kept keyboard instruments at Mottisfont: a Dolmetsch harpsichord and clavichord, and possibly a Pleyel harpsichord that he undoubtedly owned. Until recently there were few clues to this musical heritage at Mottisfont.

One exception, however, is evident in the famous trompe l’oeil panels in the Whistler room. The trophy dedicated to music consists of an ornate group of historic musical instruments – including two types of keyboard. Rex Whistler undertook this work at a time when Raymond was being home tutored; as a budding historical keyboard instrument enthusiast, Raymond may have had some influence on what was being painted. After Raymond’s death, at the age of only 41, Maud donated his keyboard instrument collection to the University of Edinburgh (in continuation of a process that Raymond had initiated). She retained two of Raymond’s most prized harpsichords for some time, perhaps as a poignant memento of Raymond’s life. At least one of these instruments was housed at Mottisfont for several years, attracting the interest of some of the country's most notable keyboard instrument makers and restorers. Alongside his collecting, Raymond’s activities as an advocate for the harpsichord had far reaching effects on the 20th-century history of the instrument.

RESEARCH - THE MAKING OF THE MODERN HARPSICHORD

Althought Mottisfont has a fine art collection and a gallery that regularly hosts important visiting exhibitions, the musical history of the property had been little investigated before 2013 and was largely obscured in interpretation of the house. This gap in knowledge was identified during the house's project for reinterpretation of the site, Storyscape, a two-year consultation with volunteers and local communities that built on the property's narrative masterplan. The National Trust then initiated a collaboration to be steered by Professors Jeanice Brooks and Laurie Stras (University of Southampton), James Rothwell (Senior Curator, National Trust) and Louise Govier (General Manager at Mottisfont). The Making of the Modern Harpsichord project aims to document the development of the harpsichord in the 20th century, a period when it saw a great transformation both in popularity and building technique, with a particular focus on Raymond Russell’s role in its revival.

At the beginning of 2014, with a Collaborative Doctoral Award from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), two PhD students, Kate Hawnt and Christopher D. Lewis, joined the team to begin research, with Christopher focussing mainly on 20th-century repertoire for the harpsichord and Kate on Raymond Russell.

Their research has so far appeared in:

Berkeley, Lennox, Suite for Harpsichord, edited Christopher D. Lewis, 2017, Chester Music (Catalogue Number: CH84810)

Hawnt, Katharine, '"Strange Luggage": Raymond Russell, the Harpsichord and Early Music Culture in the Mid-Twentieth Century,' PhD thesis, University of Southampton (2021).

Lewis, Christopher D., 'Mr Berkeley’s Toye', Lennox Berkeley Society Journal, 2016, pp. 14 – 17

Lewis, Christopher D., British Music for Harpsichord, 2016, Naxos Records (Catalogue Number: Naxos 8.573668)

Lewis, Christopher D., 'The Harpsichord in Twentieth-Century Britain,' PhD thesis, University of Southampton (2017).

An event at the 2015 Cheltenham Music Festival, where the project team presented their work with talks, live performance and videos to the general public.

A talk at The Old Operating Theatre Museum & Herb Garret in London, the site of the oldest surviving operating theatre in Europe, where Kate spoke about the life and collecting habits of Raymond Russell (which extended to the history of medicine and surgery) to the general public.

INTERPRETATION

One of the key objectives of the project has been to keep staff, volunteers and the public at Mottisfont abreast of our research and effectively distribute information. First and foremost was to inform staff and volunteers of new details discovered about Raymond and the rest of his family. This has so far been achieved by giving regular talks as part of Mottisfont’s Knowledge Exchange Programme, which hosts events to inform staff and volunteers of the latest developments in research, conservation and interpretation related to the property, as well as some training.

In the Boys' Room at Mottisfont, we have installed a small single manual twentieth-century harpsichord (built by Goble & Sons) which is on long-term loan from the University of Southampton. Christopher ran several workshops to train volunteers on how to maintain the instrument and how best to demonstrate it to visitors. He additionally made a short instructional video and paper guide for future staff and volunteers to consult. The video also explains how this harpsichord differs from an historic instrument. Staff and volunteers alike have told us that there is a great deal of interest from the visiting public in both the instrument and the history of the harpsichord at Mottisfont.

In the Boys' Room at Mottisfont, we have installed a small single manual twentieth-century harpsichord (built by Goble & Sons) which is on long-term loan from the University of Southampton. Christopher ran several workshops to train volunteers on how to maintain the instrument and how best to demonstrate it to visitors. He additionally made a short instructional video and paper guide for future staff and volunteers to consult. The video also explains how this harpsichord differs from an historic instrument. Staff and volunteers alike have told us that there is a great deal of interest from the visiting public in both the instrument and the history of the harpsichord at Mottisfont.

Kate’s research revealed that the Goble harpsichord is in the exact spot where Maud Russell kept one of Raymond’s favourite instruments, the Goermans/Taskin harpsichord, after his death. It is featured on the cover of an HMV record (where it is referred to as Couchet/Taskin) made in 1967 by Raymond’s friend, Geraint Jones, photographed in the Boys' Room at Mottisfont where it was recorded to demonstrate the French Baroque section of the album. To have an historic recording made on such an important instrument is a unique musical feature for a heritage property.

In October 2016 Christopher gave a harpsichord recital at Mottisfont of modern British harpsichord music. The main focus was the première of the British composer Lennox Berkeley’s Suite For The Harpsichord (1930). This piece was rediscovered, edited and published by Christopher as part of his thesis research. Kate has unearthed evidence of Lennox Berkeley visiting Mottisfont on more than one occasion; he and Raymond shared a mutual friend in Vere Pilkington, dedicatee of the Suite for Harpsichord, which links the piece nicely to the history of Mottisfont. The evening was co-sponsored by the Lennox Berkeley Society, and included a lecture from Kate about the life of Raymond Russell and the musical links to Mottisfont.

The next phase opened in March 2018, and used Raymond and his collection as the subject for a larger-scale interpretation on the first floor of the house. Through Kate's research findings and interpretation ideas, the story of Raymond's developing collecting interests was told in parallel with his personal story and the difficulties he encountered in his short life, with each room reflecting a different stage.

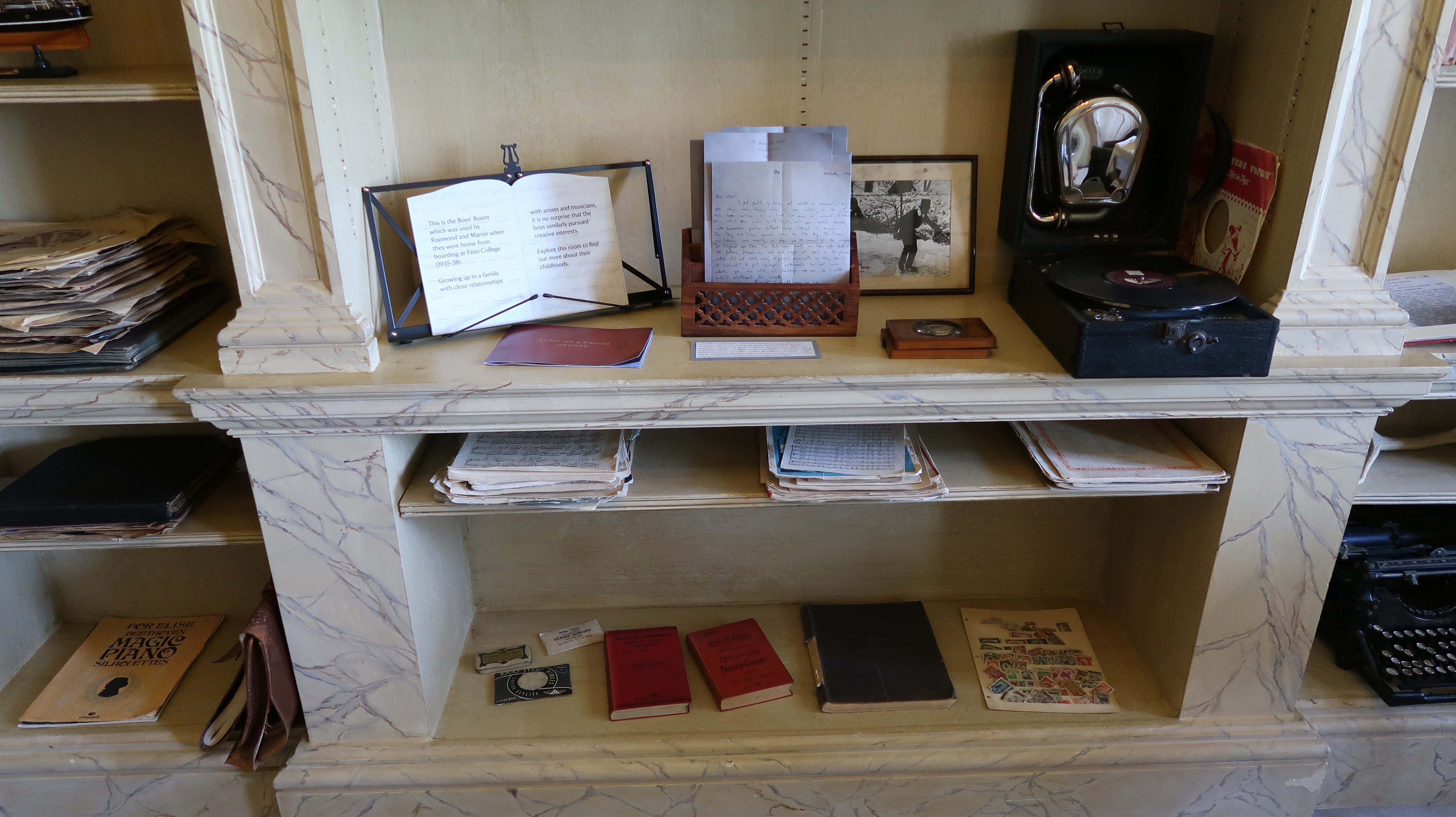

In the Boys' Room visitors were introduced to the young Raymond and his family through copies of his letters from Eton, mock ups of family photo albums, and piles of records and music, in addition to the Goble harpsichord. A quote from Maud’s diary was used to highlight the Russell boys’ early introduction to harpsichords, indicating that they attended a concert given by Violet Gordon Woodhouse in 1934. The sound of the instrument was introduced to the room via a hidden speaker that emitted a recording of someone tuning the strings, something that Raymond did regularly when at home.

In the Boys' Room visitors were introduced to the young Raymond and his family through copies of his letters from Eton, mock ups of family photo albums, and piles of records and music, in addition to the Goble harpsichord. A quote from Maud’s diary was used to highlight the Russell boys’ early introduction to harpsichords, indicating that they attended a concert given by Violet Gordon Woodhouse in 1934. The sound of the instrument was introduced to the room via a hidden speaker that emitted a recording of someone tuning the strings, something that Raymond did regularly when at home.

The Red Room was used to exhibit Raymond’s career as a harpsichordist, as Kate’s research identified it as the location for two more of his harpsichords after his death. The esteemed builder, Michael Johnson, loaned Mottisfont a single manual harpsichord, which was surrounded by chairs set out as if an audience might appear, each with copies of original concert programmes from Raymond’s recitals. Music stands additionally presented large publicity photos of Raymond sitting at different instruments. Johnson visited Mottisfont during Maud’s residence to maintain some of the instruments Raymond left behind after he died; one of these – the Goermans/Taskin harpsichord – was influential in Johnson’s instrument building business, so it is fitting that one of his instruments should be highlighted in the interpretation.

The Red Room was used to exhibit Raymond’s career as a harpsichordist, as Kate’s research identified it as the location for two more of his harpsichords after his death. The esteemed builder, Michael Johnson, loaned Mottisfont a single manual harpsichord, which was surrounded by chairs set out as if an audience might appear, each with copies of original concert programmes from Raymond’s recitals. Music stands additionally presented large publicity photos of Raymond sitting at different instruments. Johnson visited Mottisfont during Maud’s residence to maintain some of the instruments Raymond left behind after he died; one of these – the Goermans/Taskin harpsichord – was influential in Johnson’s instrument building business, so it is fitting that one of his instruments should be highlighted in the interpretation.

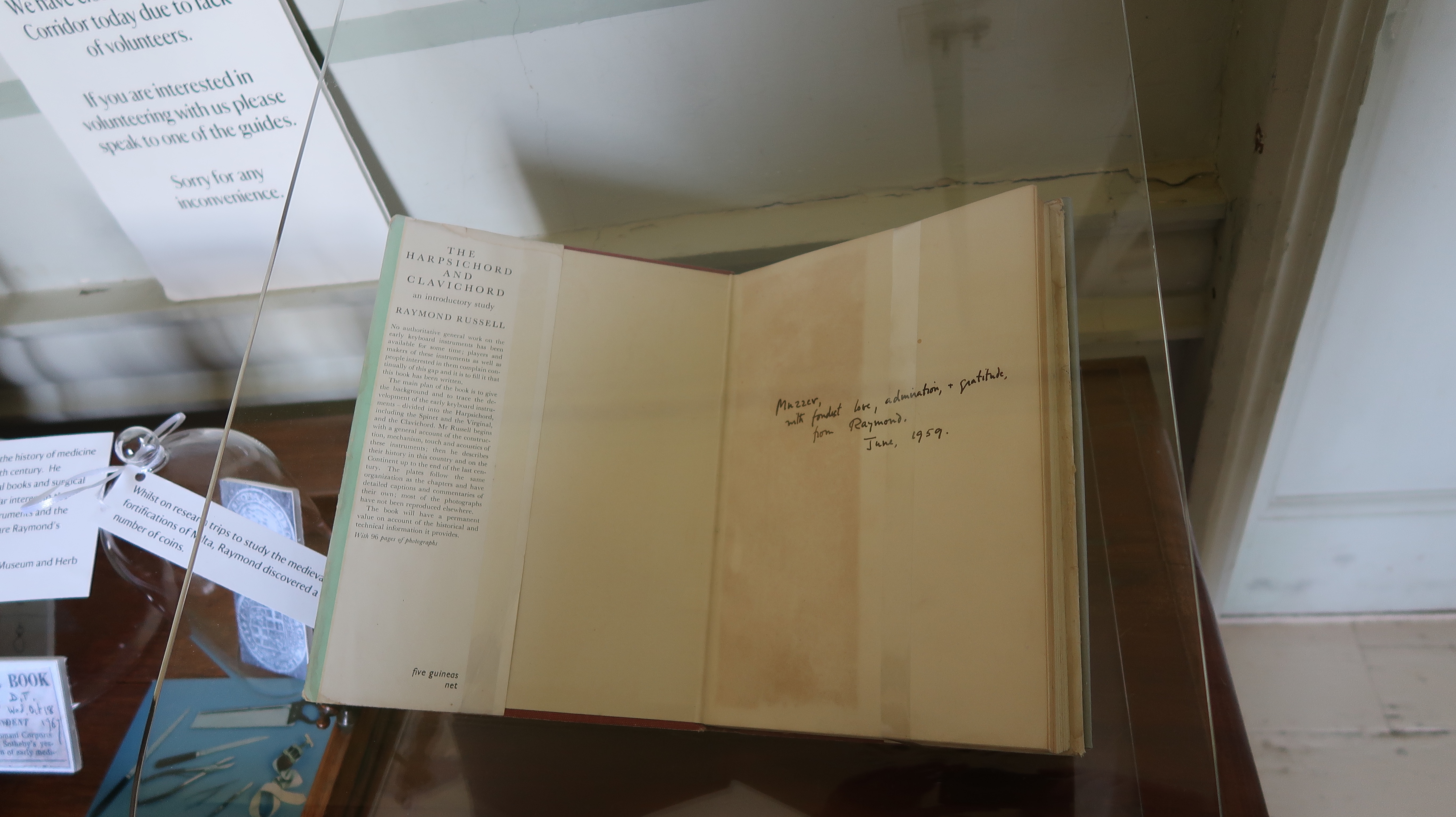

Visitors would then pass through a small Ante Room which was turned into a Cabinet of Curiosities representing Raymond’s collecting career. Bell jars were filled with examples of items that Raymond collected, including Maltese coins, surgical instruments and, of course, pictures of his harpsichords. A copy of his book The Harpsichord and Clavichord: An Introductory Study was also displayed.

Visitors would then pass through a small Ante Room which was turned into a Cabinet of Curiosities representing Raymond’s collecting career. Bell jars were filled with examples of items that Raymond collected, including Maltese coins, surgical instruments and, of course, pictures of his harpsichords. A copy of his book The Harpsichord and Clavichord: An Introductory Study was also displayed.

The final room dedicated to Raymond’s narrative was the Dining Room. This was presented as an homage to Raymond’s life and his mother’s efforts to ensure his work was remembered. A radio and headset gave visitors the opportunity to listen to Raymond’s opinions on 20th century harpsichord building, through a reproduction of a BBC Third Programme broadcast he gave. The table was set for dinner with each place setting representing a different friend or relative of Raymond’s. Snippets of conversations about completing the posthumous donation of Raymond’s keyboard collection to the University of Edinburgh were printed on napkins, placed on their relevant person’s plate.

The table was set for dinner with each place setting representing a different friend or relative of Raymond’s. Snippets of conversations about completing the posthumous donation of Raymond’s keyboard collection to the University of Edinburgh were printed on napkins, placed on their relevant person’s plate.

Feedback from National Trust staff and visitors was very positive. Many had expected an exhibition based on a harpsichord collector to be dry and uninteresting, but found themselves drawn in by the details of Raymond’s colourful, short life. The availability of a high quality, well-maintained harpsichord enabled live musical events, attracting further attention to Raymond and his harpsichords. These events attracted visitors of all ages to new sounds, instruments, and the possibility of a musical heritage associated with an historic property.