Erddig's Harmonium from Church to Home

Erddig is a treasure trove of keyboard instruments: the house boasts two grand pianos, a sizeable pipe organ in the Entrance Hall, an American organ in the chapel, musical curiosities such as the portable Crane and Sons harmonium and - slightly hidden from the main path in the Tribes Room - a fine example of a French harmonium. This instrument tells stories of family life in the late nineteenth century, of acts of domestic piety, and of Sunday evenings whiled away to the sounds of music. Recovering its tones and its music forms part of a project that seeks to rediscover Erddig in new ways through its sounds.

Country houses of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries often have their own chapels, providing a dedicated space for worship within the home. At the same time, domestic devotional activities also took place in other rooms; spiritual life was not confined to formal worship in chapels. And many country houses maintained close relationships with local religious establishments — from grand cathedrals to small parish churches — where families might regularly worship or which were sites for family graves.

The National Trust property of Erddig in North Wales is a good example: it possesses its own chapel, but the Yorke family was also heavily involved with the church of St Deiniol and St Marcella in nearby Marchwiel. They regularly contributed funds for its upkeep and embellishment, while maintaining their status as a leading local family through visible contributions to the church fabric. A stained glass window depicting the Yorke family tree overlooks the family vault outside the window; inside the church are further memorials to various family members, including an especially beautiful monument to the teenage musician Anne Jemima Yorke that was donated by her mother in 1770.

Musical practices flowed between these domestic and public spaces, and included both formal worship and informal devotion. Throughout this period, organs were increasingly installed in country houses in a variety of locations – including entrance halls, libraries, and music rooms as well as chapels. House organs were often used for devotional purposes, such as playing religious music or accompanying hymns, particularly on Sundays. When the Earl of Exeter died in 1797, for example, the obituary for the Gentleman’s Magazine commented that his house at Burghley featured a fine organ in the parlour near the North entrance hall, “which when played of a Sunday, attracts a great concourse of strangers to the park gate.” But they were also used for dancing and more general music making. Erddig again provides a striking example: in 1865, 15-year-old Philip Yorke II acquired a fine Bevington organ, which was installed in the house’s Entrance Hall that sits between chapel and drawing room. Extant scores at Erddig include both sacred and secular music for organ, and the instrument was also furnished with a “dumb organist,” a device fitted to the keyboard, which plays opera and dance tunes using a barrel mechanism driven by turning a handle.

In the nineteenth century, a new instrument arrived to occupy a similarly fluid physical and musical space: the harmonium. This was a form of reed organ, which produces sound by blowing air over reed tongues rather than through pipes. Experimentation with reed organ manufacture exploded in Europe and the United States, and new patents proliferated: these encompassed a wide variety of designs, using either suction or pressure to generate the air flow, and ranging from simple single-manual examples to elaborate double- and triple-manual instruments with multiple sets of reeds and ingenious mechanisms for shaping tone colour and volume. Compact and robust, the reed organ became enormously popular in the mid- to late nineteenth century, both as a parlour instrument at home and in churches and chapels as a versatile and practical alternative to the pipe organ. Huge numbers were shipped to European colonies, where they were used in missions, churches and homes.

The French harmonium or orgue expressif was among the most successful and popular forms of reed organ, and the harmonium at Erddig was almost certainly made by the Parisian manufacturers H. Christophe and Etienne. The instrument is very similar to a harmonium at Ightham Mote produced by the same manufacturers, and a stamp on the side of the lowest key-lever names the supplier: MONTI & FILS AINÉ / 127 RUE OBERKAMPF PARIS (trading under this name from 1868-1878).

According to the memoirs of Louisa Yorke (née Scott), the harmonium was first used in the parish church at Marchwiel before coming to Erddig. It is likely that the instrument was installed there shortly after it was manufactured, at a moment when the harmonium presented an attractive prospect for churches that had lost or never possessed an organ, and it probably represents a gift from the Yorke family. Further research in local archives may confirm this hypothesis, which is supported by the later history of the instrument. In 1888, St Deiniol and St Marcella did in fact acquire a new pipe organ, donated by the widow of Benjamin Piercy at Marchwiel Hall in memory of her husband. As Louisa Yorke remembered,

The large Harmonium was used for many years in the church at Marchweil and came to Erthig when a new Organ was built in the church about 1888 or 89, about the time that old Mr Sturkey [vicar of Marchwiel church] died. For many years it lived in the present Drawing-room and was much played on by Victoria Yorke. In 1902 it was brought down to the Tribes-room to make room for other furniture. (Louisa Yorke, Facts & Fancies at Erthig on the Dyke, MS c.1924, North East Wales Archive D/E/303).

Victoria Yorke, Louisa’s mother-in-law, was an accomplished keyboard player whose abundant collection of sheet music for piano still survives at Erddig. She seems to have relished the opportunity to expand her musical palette and experiment with the novel sounds of the harmonium.

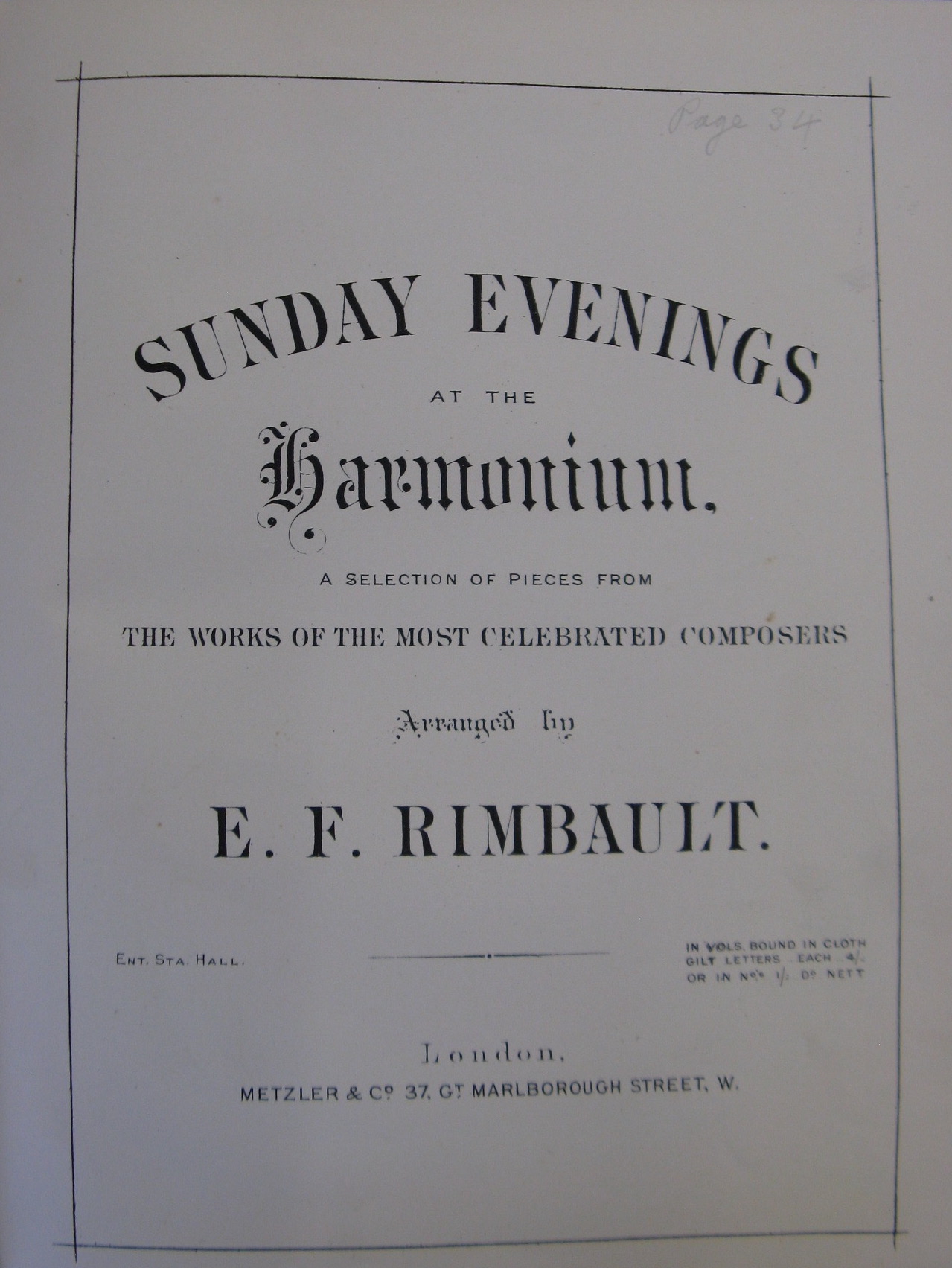

Erddig’s extensive sheet music collection includes repertoire that is specifically designated for harmonium, or for either harmonium or organ, which gives a good idea of the very broad range of music that was considered appropriate for the instrument. The pieces in Sunday Evenings at the Harmonium, a collection of arrangements by Edward Francis Rimbault, first appeared in 1868 separately as installments in a monthly magazine, Exeter Hall, and were advertised as “especially adapted for Sunday evening in the family circle” Illustrated London News, 28 December 1867). As a separately-published volume, Sunday Evenings at the Harmonium offered a compendium of extracts from works by prominent composers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries such as Couperin, Handel and Mozart; though all of the repertoire features sacred titles, some of it was in fact adapted from secular sources such keyboard suites and opera extracts. It is not known who owned or used the copy at Erddig; the book may have been used to play on Erddig’s organ before the harmonium was installed at Erddig c. 1888.

Erddig’s extensive sheet music collection includes repertoire that is specifically designated for harmonium, or for either harmonium or organ, which gives a good idea of the very broad range of music that was considered appropriate for the instrument. The pieces in Sunday Evenings at the Harmonium, a collection of arrangements by Edward Francis Rimbault, first appeared in 1868 separately as installments in a monthly magazine, Exeter Hall, and were advertised as “especially adapted for Sunday evening in the family circle” Illustrated London News, 28 December 1867). As a separately-published volume, Sunday Evenings at the Harmonium offered a compendium of extracts from works by prominent composers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries such as Couperin, Handel and Mozart; though all of the repertoire features sacred titles, some of it was in fact adapted from secular sources such keyboard suites and opera extracts. It is not known who owned or used the copy at Erddig; the book may have been used to play on Erddig’s organ before the harmonium was installed at Erddig c. 1888.

In the video below, harmonium specialist Jonathan Scott provides an introduction to Erddig’s harmonium and its construction. Our harmonium video gallery features more videos of Jonathan Scott’s performances of complete pieces from Erddig’s sheet music collections. To hear more harmonium recordings, visit Sounding Erddig - a free online repository of sound and music from Erddig’s instruments, music collections, and spaces – where you can find further information as well as music for harp-lute, organ, piano, voice and more. While the harmonium is enjoying a revival at present, its sounds are still unfamiliar to many visitors to historic houses today. But through the sounds, the harmonium can help us imagine a small family group assembled in the dark yet cosy space of the Tribes Room on a Sunday evening, listening to and perhaps singing along to some of this music.