Dance at Boughton House

Boughton House (Northamptonshire), the seat of the Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch, is among the best-preserved Baroque stately homes in Britain. The house and gardens are open to public during part of the year through the Buccleuch Living Heritage Trust.

Boughton House was first built in the early 16th century, but as it stands today is largely the work of Ralph Montagu, later 1st Duke of Montagu, who inherited the estate in 1683. Montagu had been English ambassador to France, and embarked on an ambitious programme of expanding and rebuilding Boughton House in the French style, employing large numbers of Huguenot artists and craftsmen. The house was a centre of activity until the mid-18th century, when it passed through the female line to families who had residences elsewhere. Boughton remained little occupied until the early 20th century, when the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry, a descendent of the Montagus, began to return family collections to Boughton.

RESEARCH

The present Duke of Buccleuch inherited a large music collection amassed by the Montagus from the late 17th century onwards. Key collectors were John, 2nd Duke of Montagu (1690-1749), his granddaughter Elizabeth Montagu (1743-1827) who married the 3rd Duke of Buccleuch in 1767, and her daughters. During the 19th century a large amount of material (particularly with Scottish links) came to the family from the Edinburgh dealer and collector Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe (d. 1851). The music and dance collections are being brought together at Boughton from several Buccleuch houses in Scotland and England, with a long-term view to establishing a music research centre; meanwhile access of necessity is limited until a detailed catalogue is complete. Jennifer Thorp (Archivist, New College Oxford and part of the editorial advisory committee for Historical Dance) is cataloguing and researching the collection's dance items, in association with Paul Boucher (Music Advisor and Artistic Director with overall responsibility for the Montagu Music Collection [MMC]) and Crispin Powell (Archivist to the Buccleuch estates). These comprise c. 50 of the 463 volumes in the MMC that were roughly listed by Patrick and Rachel Cadell in 2009; and dance is also a significant component of many full scores of operas (by, for example, Lully, Handel, Gluck, and Grétry). Among other material, the collection includes rare 18th-century dance manuals and notated dances, mainly French; dance music for the violin, including manuscript material from the early 18th century; keyboard arrangements of dance music from stage works performed in London in the late 18th and early 19th centuries; and collections of Scottish dances and reels in both print and manuscript.

Jennifer Thorp's research on the collection has been presented in:

'He who pays the Piper: the Montagu family as patrons of dance in eighteenth-century London' (paper delivered at the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies conference, Oxford, January 2014).

'Celebrity Patrons: the Montagu family and dance throughout the eighteenth century' (paper delivered at the annual Oxford Dance Symposium, Oxford, March 2014).

'Mrs Elford, stage dancer and teacher in London, 1700-1730' (paper delivered at the Early Dance Circle conference, Bath, April 2014; published in Ballroom, Stage and Village Green: Contexts for Early Dance, ed. Barbara Segal and William Tuck, EDC Publications, 2015).

Jennifer can also be seen talking about dance at Boughton House here.

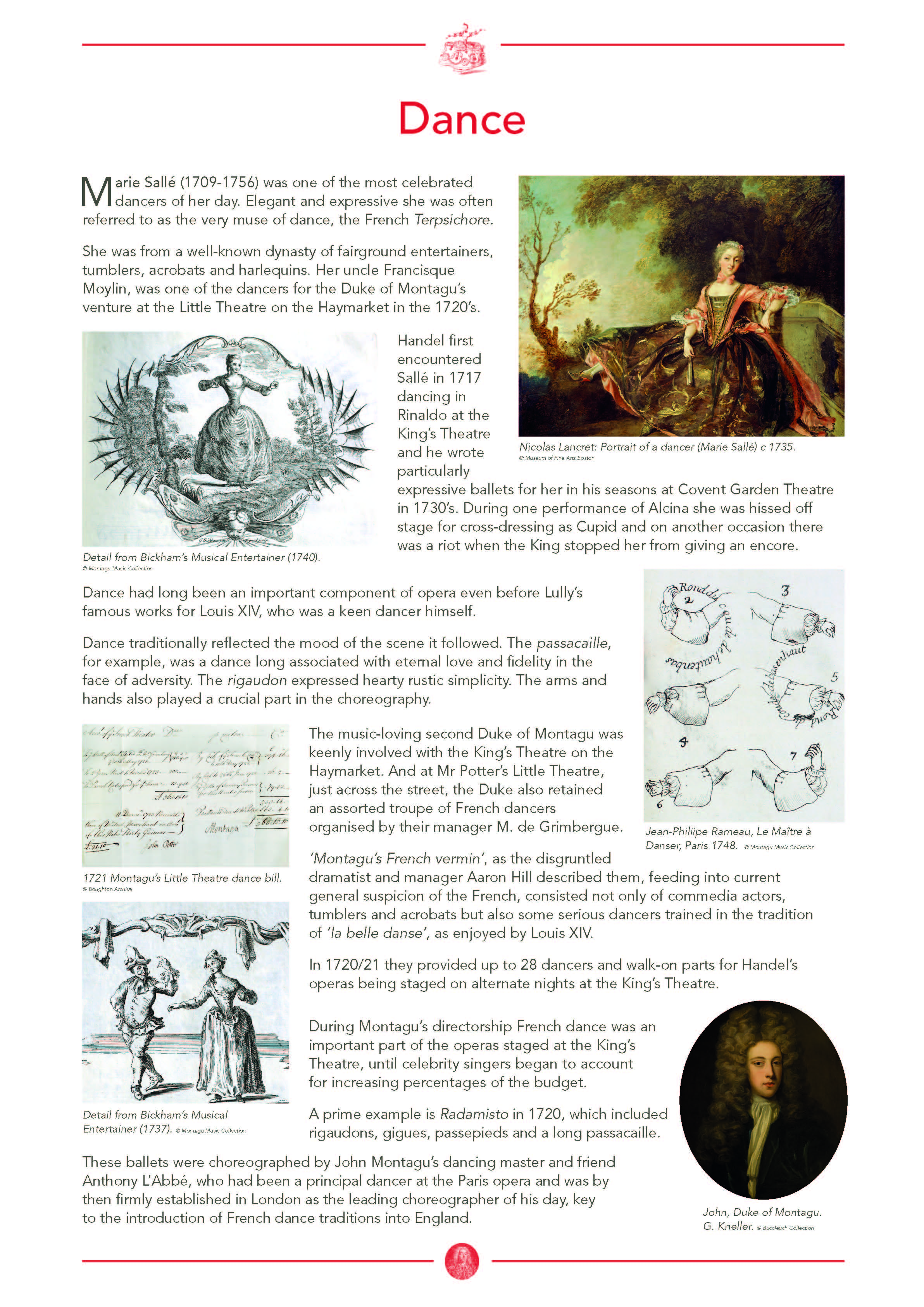

INTERPRETATION

The Calligraphy of Dance (2014)

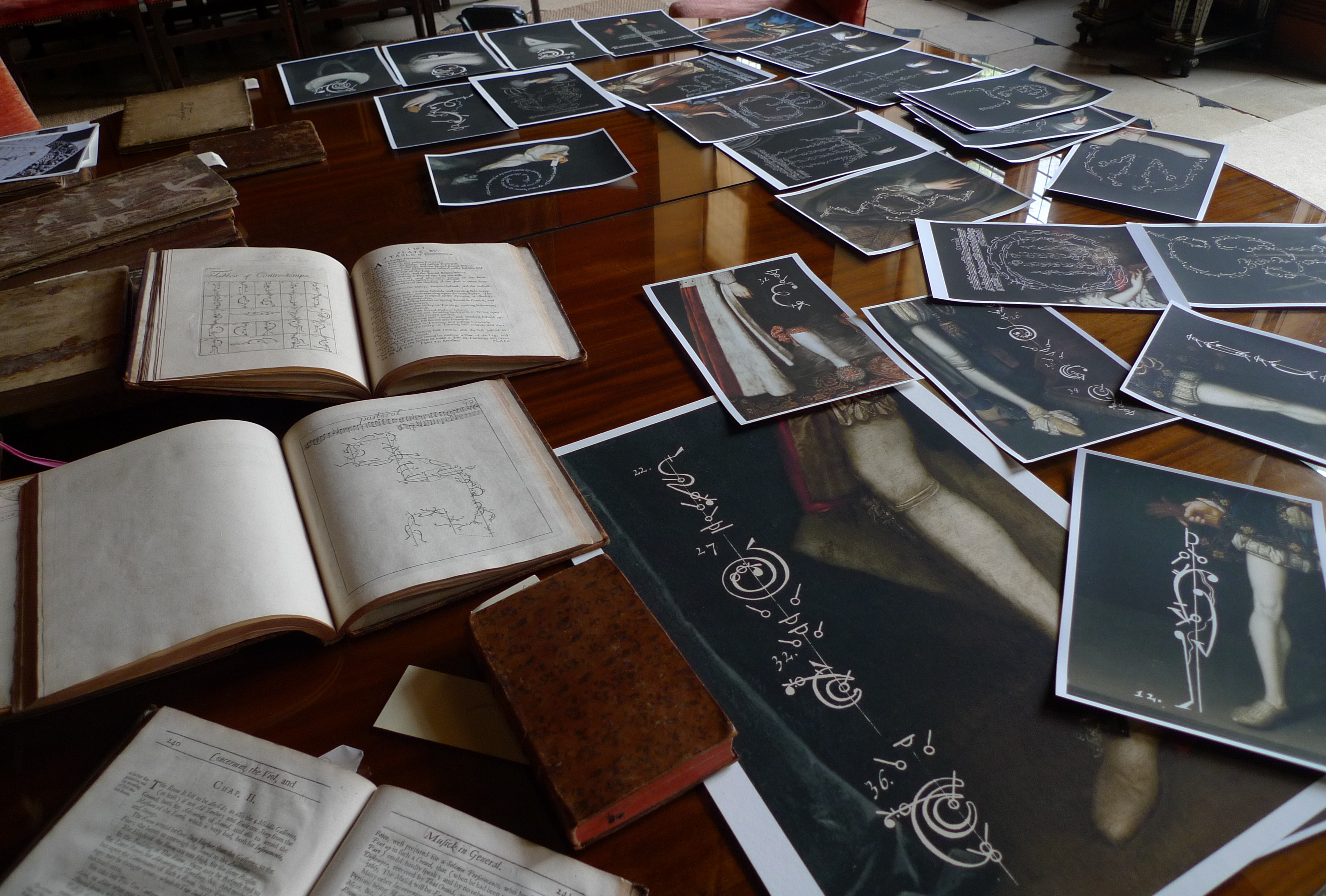

The brief for interpretive work, at Boughton and elsewhere, on this collection has been that concerts and performances should reflect holdings of dance and music materials in the MMC, and thereby bring the collections to life; and that events at Boughton should occur in conjunction with special exhibitions in the house. Paul Boucher organised the first such exhibition after realising that, apart from their role in preserving dance forms and traditions by their detailed choreographic information, early dance notations are also visually intriguing, with their strange, abstract graphics. Boucher approached the award-winning photographic artist Tessa Traeger, who spent an initial day consulting the dance material and visiting the house to imagine how to bring the musical sources into dialogue with the setting. She followed up with several days of shooting the dance material and the many early family portraits that line Boughton’s walls in great detail, to produce a series of 48 original artworks under the title The Calligraphy of Dance.

The images deploy fragments of Beauchamp-Feuillet dance notation as purely graphic embellishments to details of costumes and limbs taken from the portraits. The works were shown in an event at Boughton in September 2014 before moving to the Purdy Hicks Gallery, London. Images from the catalogue can be seen here.

The event included an introduction to Traeger’s photographic exhibition by the artist, combined with tours of the house and gardens in two groups of 30. As the culmination of the tour, each group experienced a concert of dance and music in the Great Hall (so that the performance was given twice, with close coordination of timing between the tours and the concerts). The costumed concert, which concentrated on dances known to John, 2nd Duke of Montagu, featured Baroque flautist Jed Wentz (Amsterdam) and harpsichordist Silas Wollston (Cambridge), and dancers Irène Fest and Hubert Hazebroucq (from the Paris-based group Les Corps Eloquents) in addition to Jennifer Thorp. Speaking between the dances, Thorp explained their link with the Montagu family, the aesthetic of early 18th-century dances, and the way they were recorded in calligraphic notation.

Minuet and Masquerade: Dances and the Dukes of Montagu (2015)

Research on Boughton's collections underpinned events for the Utrecht Oude Muziek Festival (28 August - 6 September 2015), which was themed 'England, My England'. The festival featured several ‘From the Duke’s Library’ concerts of music and dance based on examples from the MMC. A documentary film produced for the festival featured material on Boughton House and its early owners and collections (the segment appears in English at approximately 3.12, after the introduction in Dutch). Jennifer Thorp and Paul Boucher presented papers on the MMC at the concurrent Zomerschool workshops. The two dance performances took up the themes of the Montagu family’s dynastic marriages, masquerades at the London house and at court, Duke John’s patronage of the Little Theatre in the Haymarket during the 1720s and his apparent involvement in the Bottle Conjuror’s hoax there in 1749. The dances came from MMC sources, supplemented by other suitable notated dances, and used new choreographies by Hubert Hazebroucq to music from the collection. Thorp provided a script, which was translated into Dutch for delivery by music director Jed Wentz, and she was joined for the dances by three dancers from Les Corps Eloquents. The musicians were Wentz's Festival Consort, two of whom quit their instruments at one point to don masks for the masquerade’s country dances.

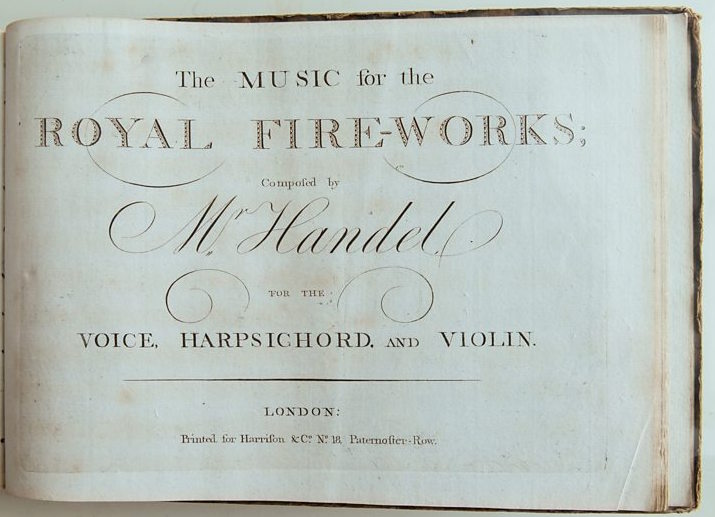

Handel at Boughton (2016)

In 2016 Paul Boucher, in consultation with Jennifer Thorp, built on this work by incorporating the story of dance into an exhibition on Handel for Boughton House. Handel was keenly aware of the French dance tradition and used dance extensively in his earlier operas. Rather than attempt a full biographical retrospective, the exhibition thus presented selected facets of Handel’s life, focusing partly on the history of dance, which was refracted through the story of the Montagu family and the King’s Theatre, Haymarket. The public were able to experience Handel through a series of informative panels as well as a varied series of objects in the exhibition cases. The panels were hung in a section of the house that remained unfinished, adjacent to the room housing the exhibits.

Among the items on display were instruments used by Handel in Music for the Royal Fireworks (on loan from the Bate Collection, University of Oxford), a 1750’s Chelsea porcelain orchestra, a harpsichord from 1720 thought to have belonged to Handel, a bust of Handel after Louis François Roubillac, several first edition Handel scores from the MMC and a glimpse of the lunch menu when Handel visited Montagu House in 1747.

The format of the event was similar to that of The Calligraphy of Dance. Joining the 4 dancers of Les Corps Eloquents and the French instrumental ensemble Concordia was countertenor James Laing, who drew together effectively an act of Handel opera using material (both choreographic and vocal) from the collection, including the only two surviving contemporary choreographies to Handel’s music.

The production was inspired by Terpsichore, the new prologue Handel wrote for his 1712 opera, Il Pastor Fido, in which Apollo was sung by the castrato Giovanni Carestini and Terpsichore was danced by Marie Sallé.

To bring the event fully into the 21st century, composer Luke Styles and choreographer Hubert Hazebroucq were commissioned to create the final scene. Passacaille is a re-imagining of the passacaille that appears in three of Handel’s dramatic works - Radamisto, Parnasso in Festa and Il Pastor Fido - set to a poem by Mark Turbyfill. The increasing fragmentation of Baroque musical idioms is mirrored by the fragmentation of Baroque dance figures.

Reports on the exhibition and event featured in Gramophone and in BBC Radio 3's In Tune.