The Harp-lute at Erddig: Music, Fashion and Technology

The harp-lute at Erddig tells the story of the nineteenth-century interest in technological development and new instruments, and the desire to show education and social class while relishing small yet telling luxuries. Highly fashionable among the upper middle classes of Regency England, it was eventually superseded by other musical inventions, and until recently remained a silent witness to Erddig’s past. With the assistance of the Erddig house staff, several instrument conservators and one of the few modern-day players of the instrument, we have recorded the instrument in situ. This project forms part of the attempt to bring the sounds of Erddig back to life and to explore the house through its sounding history.

The music room at Erddig near Wrexham in North Wales offers a spectacular sight: the East wall features a fine organ by Bevington & Sons; by its side stands a baby grand piano, and across the room each item of furniture serves as a pedestal for a different musical instrument or playback device. These range from an ostentatious gramophone to a miniature automaton piano player - a little figurine dressed in tail coat and trousers of felt, sat at an upright piano no higher than 13.5 centimetres. Among this curious collection of mechanical marvels, the visitor may spot an instrument that cannot quite decide whether it is a lute or a harp, with its vaulted back and fingerboard extending upwards into an Orphic shape from which the strings are suspended.

Amid piles of sheet music in another room are two volumes that bind together four books of music for this strange and fascinating hybrid instrument, along with pencil annotations showing that someone put the scores to use.

Erddig is among only four National Trust properties that own one of these once hugely popular instruments. It is unique in holding not only a harp-lute but also its original case, along with contemporary musical publications. While it is not entirely clear how and when the instrument came to Erddig, its presence is perhaps no surprise: over the years, members of the Yorke family played and enjoyed a large collection of musical instruments, some of which are lost today. These instruments share a common feature: they combine a predilection for technological mastery and gadgetry with a love for comfortable domestic luxury. None of them is ostentatious, yet they are precious, intricate and often quirky.

We explored this fascinating collection as part of the research project “Music, Home and Heritage: Sounding the Domestic in Georgian Britain,” funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council of Great Britain and led by Jeanice Brooks (University of Southampton) and Wiebke Thormählen (Royal College of Music). The musical past of Erddig has been a key focus of this project.

Erddig has been home to the Yorke family since 1733, when Simon Yorke I (1696-1767) inherited it from his uncle John Meller. The house’s history is well documented in the many artefacts amassed during the family’s continuous habitation until 1973, when Erddig and its contents were given to the National Trust by Philip Yorke III (1905-1978). Yet this story has often been narrated along the line of male heritage, in this case four Simons interspersed with three Philips, following conventions of country house history. Looking at the house through its musical life has allowed us to rediscover – and, crucially, to hear – some of its female inhabitants.

The harp-lute likely came to Erddig through Victoria Maria Louisa Cust (1823-1895) who married Simon Yorke III in 1846. Victoria’s father, General Sir Edward Cust, was the sixth son of Sir Brownlow Cust, 1st Baron of Belton Hall in Lincolnshire, while her mother, Mary Ann Cust, née Boode, was Woman of the Bedchamber to the Duchess of Kent. As a result, the five-year-old Princess Victoria became godmother to Victoria Mary Louisa, a bond that was honoured through various gifts. A family connection to the maker of Erddig’s harp-lute, Edward Light, who enjoyed royal patronage, may have been made around this time. As she grew up, Victoria Yorke was clearly interested in music: five binder’s volumes at Erddig include her signatures and annotations and two further volumes are likely to have been hers. In many instances she signed with her married name, indicating that she continued to pursue her musical activities throughout her married life and motherhood. A photo album from the 1860s shows the harp-lute posed in the Chinese Room at Erddig; the album also includes photographs of Leasow Castle, Victoria’s childhood home, suggesting that both album and instrument were hers by this time.

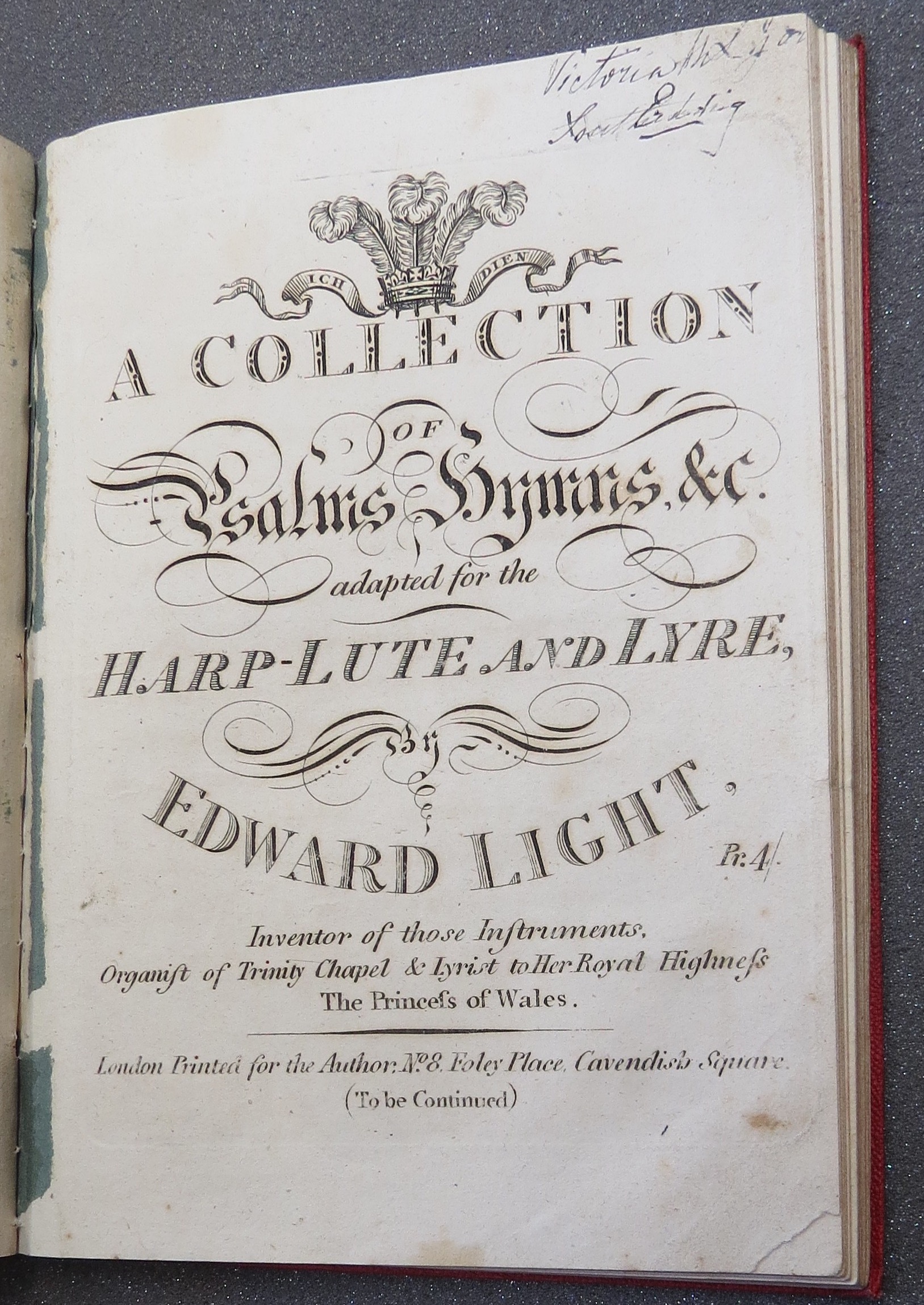

The Erddig harp-lute is especially precious as it remains in good condition and can still be played on occasion today. Unusually, it is complete with its fitted case and ribbon just as its maker, Edward Light, sold it. What’s more, it has been kept together with four volumes of harp-lute music: a rare copy of Edward Light’s Introduction to the Art of Playing on the Harp-Lute and Apollo-Lyre points to the interest in a range of new instruments offered for the domestic market. It takes the player from the basics of clef reading and rhythmic notation to learning popular songs in easy arrangements. A Collection of Songs properly adapted for the Harp-lute, Lyre and Guitar similarly attempts to reach a broad market through its title, while the Preludes, Exercises and Recreations for the Harp-lute and Apollo-lyre extends into a more advanced level of exercises before offering famous opera arias in arrangement. A final volume, A Collection of Psalms & Hymns adapted for the Harp-lute and Lyre, suggests that the instrument could be used to accompany the sacred as well as secular songs. Victoria signed some of these books with her married name, and added the inscription “Erddig” over the top of what may have been a previous ownership mark or, perhaps, a previous location. The musical annotations in pencil to some of the books may also be hers; whether or not this is the case, they indicate that someone in the Cust or Yorke families was an active player.

When Edward Light patented the instrument in 1818 he appealed to the domestic market: the instrument was portable, comparatively easy to learn and much more affordable than the piano. The music collections he masterminded alongside the instruments consisted of a range of popular song and opera tunes, familiar dances, well known highlights from recent orchestral repertoire, and simple sacred music designed to be played in the parlour. But in his design, he also appealed to desires for technological ingenuities and for little luxuries. The tuning key, for instance, was simple enough to operate, thereby cutting the costs of bringing in the tuner that the harp proper demanded, and operating this little device gives one the sensation of winding up an intricate clock or musical automaton. Light’s gilded adornment of the black wood similarly invites the hands to caress an instrument inscribed with preciousness.

When Edward Light patented the instrument in 1818 he appealed to the domestic market: the instrument was portable, comparatively easy to learn and much more affordable than the piano. The music collections he masterminded alongside the instruments consisted of a range of popular song and opera tunes, familiar dances, well known highlights from recent orchestral repertoire, and simple sacred music designed to be played in the parlour. But in his design, he also appealed to desires for technological ingenuities and for little luxuries. The tuning key, for instance, was simple enough to operate, thereby cutting the costs of bringing in the tuner that the harp proper demanded, and operating this little device gives one the sensation of winding up an intricate clock or musical automaton. Light’s gilded adornment of the black wood similarly invites the hands to caress an instrument inscribed with preciousness.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, harp-lutes accrued an association with antiquity: the Pre-Raphaelite painter Arthur Hughes, for instance, uses the harp-lute as an emblem of feminine learned yet domesticated intimacy in his A Music Party (1864). Whether Victoria played the harp-lute remains unclear, but she clearly harboured an antiquarian interest in the instrument. In 1874 she loaned it to the temporary museum in Wrexham as a display item; and an 1876 letter from the notable Welsh composer Brinley Richards confirms her interest in musical instruments and suggests she showed the harp-lute to him on a visit to Erddig (Flintshire Record Office, D/E/1542/438). In 1896, the books were bound together into two volumes by Victoria’s cousin Robert Henry Hobart Cust, a scholar and Renaissance historian who inherited some of Victoria’s valuable antique possessions. By this time the harp-lute was no longer a fashionable parlour instrument, but a historical curiosity.

The Erddig harp-lute tells tales of female ownership and collectorship and a woman’s mark on the house and its contents. It conjures the ripples of the early nineteenth-century interest in musical accomplishments as they broadened across society, and shows how the ingenuity of contemporary technology was applied to products for the domestic music market.

In the mini documentary below you can hear the Erddig harp-lute played by Taro Takeuchi, one of the few performers today who have taken up the instrument again. We follow conservator Michael Parfett through preparing the instrument for recording, and see its idiosyncratic combination of luxury and technology close up. Researcher Wiebke Thormählen tries her hand at the harp-lute, experimenting with the amateur learning of the instrument and reimagining the twined threads of 19th-century musical fashion and technology. In addition to the mini-documentary, three further short films that show both the variety and simplicity of music arranged for the harp-lute are available on the Video Galleries Page.