Dance Names: Making Dance Personal

A glance at any collection of dances from the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries reveals a wide variety of names associated with individual dances. Dance names drew on a plethora of topics, including: leisure pursuits (pleasure gardens, spas, races, archery); locations which paid tribute to domestic tourism (castles, palaces, stately homes and towns); cultural commodities (plays, operas, ballets, popular songs, literature, dancers and sometimes composers); military associations in times of war; evocations of exoticism, rusticity and national identity; and, of course, people (Goff 2016). Dance collections, therefore, can be viewed as social and cultural documents, which not only indicate the popularity of a given dance form, but through their individual titles can also act as a compendium of popular (often elite) preoccupations. In turn, both these preoccupations and the dance collections themselves tapped into practices such as patronage, consumerism and luxury, spreading tentacles across artforms and spaces. Sets of dances issued by publishers were clearly aimed at an audience that had the resources to purchase music, and also an understanding of the cultural references within.

John Preston’s Twenty four Country-Dances for the Year 1788 illustrates the diversity of dance names that occur within a single publication. After Worcester Races and Don Juan are references to Scottish culture (The Tartan Plaiddie), tropes of antiquity and pastorality in The Druids and The Peasant, and of otherness in The Arabian Prince. Preston’s use of The Grotto linked the ephemeral past with its more solid recreation in landscaped gardens on country estates. Such estates included Studley Park near Ripon in Yorkshire; Hazlewood Hall, possibly the seat of John Beighton in Derbyshire; and Fitzroy Farm, a ferme ornée (ornamental farm) in Highgate which was the seat of Charles FitzRoy, 1st Baron Southampton (Deason 2016). The collection also included Buxton Assembly, in a double nod to a spa town and the act of dancing itself.

John Preston’s Twenty four Country-Dances for the Year 1788 illustrates the diversity of dance names that occur within a single publication. After Worcester Races and Don Juan are references to Scottish culture (The Tartan Plaiddie), tropes of antiquity and pastorality in The Druids and The Peasant, and of otherness in The Arabian Prince. Preston’s use of The Grotto linked the ephemeral past with its more solid recreation in landscaped gardens on country estates. Such estates included Studley Park near Ripon in Yorkshire; Hazlewood Hall, possibly the seat of John Beighton in Derbyshire; and Fitzroy Farm, a ferme ornée (ornamental farm) in Highgate which was the seat of Charles FitzRoy, 1st Baron Southampton (Deason 2016). The collection also included Buxton Assembly, in a double nod to a spa town and the act of dancing itself.

The fact that many titles had no connection with the actual dances, except where the music was extracted from other works such as stage productions, was beside the point. The need to market something enticing and fresh was wryly observed by the dancing master Thomas Wilson in 1824:

Nothing’s too little or too mean to steal,

For want of genius, they’ll nick name a reel,

And give it some strange French, or mongrel name,

To make folks think it new and not the same (78)

What publishers were offering was a little imaginative conjuring, a kind of virtual journey in which the act of dancing was joined to the visual imagery of the titles through memory, and emotional and sensory associations. Their collections captured a way of life in a condensed form, expressive of their time.

Patronage and Personal Connections

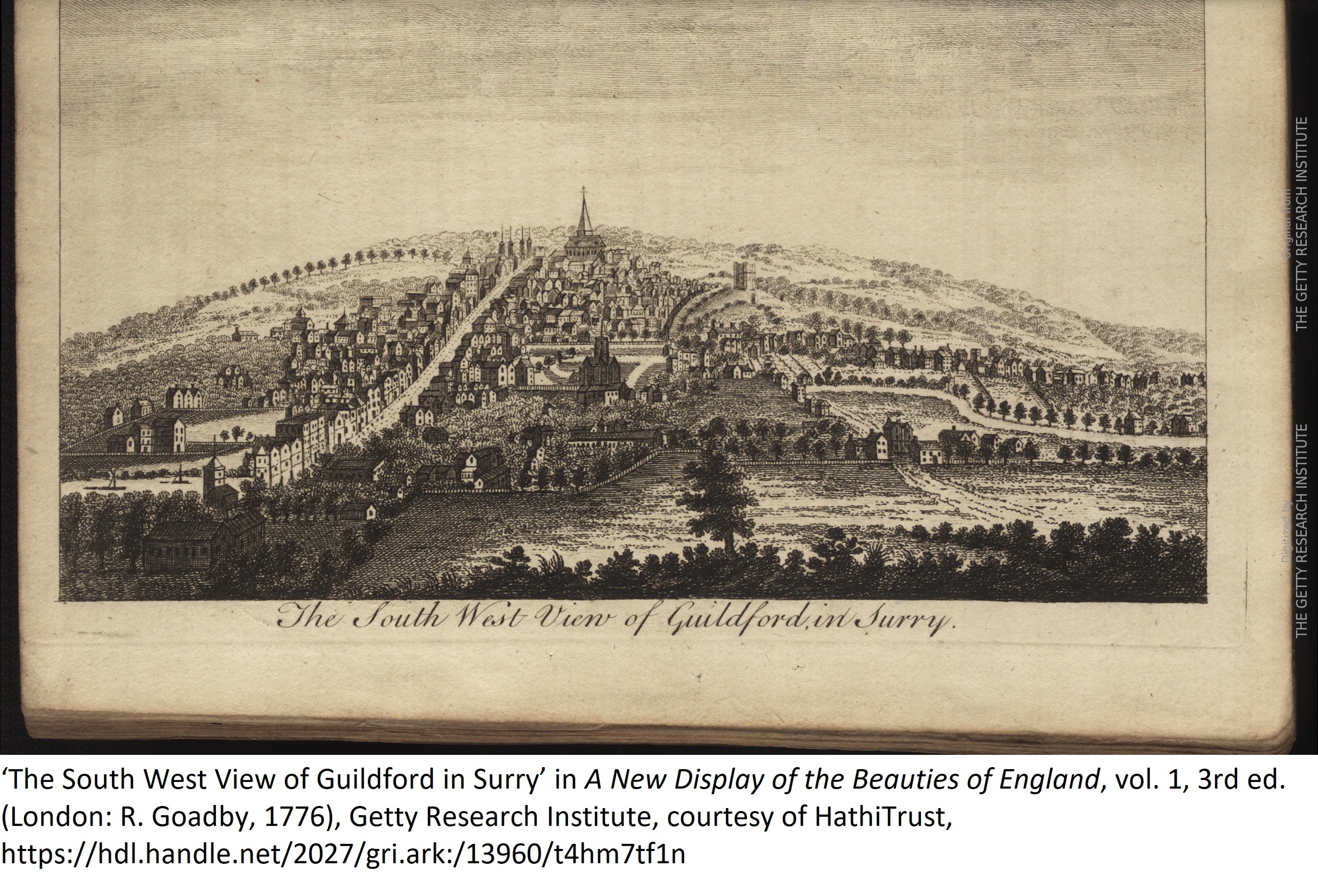

In addition to highlighting generic aspects of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century life, dance titles also reflected themes of patronage and personal connections. This was particularly evident for dancing masters and composers who produced their own dances. James Fishar’s Twelve New Country Dances, Six New Cotillons and Twelve New Minuets (1778) contains five dances named after members of the Lennox family, who make up six of the top seven subscribers in the attached subscription list. Fishar advertised himself as an experienced dancer and ballet master with the Covent Garden and King’s theatres, and may have taught some of the Lennox family. On 17 November 1777, the Morning Chronicle announced the intended publication of Fishar’s work, where he also advertised a forthcoming ball in Chichester. This was close to the Lennox seats of Goodwood and West Stoke, and appeared in his publication as the Chichester Minuet. The companion Guildford Minuet reflects the location of Fishar’s own home, while Miss Manessier’s Minuet may have been a tribute to his late wife or a family member (Highfill Jr., Burnim and Langhans 1978).

In addition to highlighting generic aspects of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century life, dance titles also reflected themes of patronage and personal connections. This was particularly evident for dancing masters and composers who produced their own dances. James Fishar’s Twelve New Country Dances, Six New Cotillons and Twelve New Minuets (1778) contains five dances named after members of the Lennox family, who make up six of the top seven subscribers in the attached subscription list. Fishar advertised himself as an experienced dancer and ballet master with the Covent Garden and King’s theatres, and may have taught some of the Lennox family. On 17 November 1777, the Morning Chronicle announced the intended publication of Fishar’s work, where he also advertised a forthcoming ball in Chichester. This was close to the Lennox seats of Goodwood and West Stoke, and appeared in his publication as the Chichester Minuet. The companion Guildford Minuet reflects the location of Fishar’s own home, while Miss Manessier’s Minuet may have been a tribute to his late wife or a family member (Highfill Jr., Burnim and Langhans 1978).

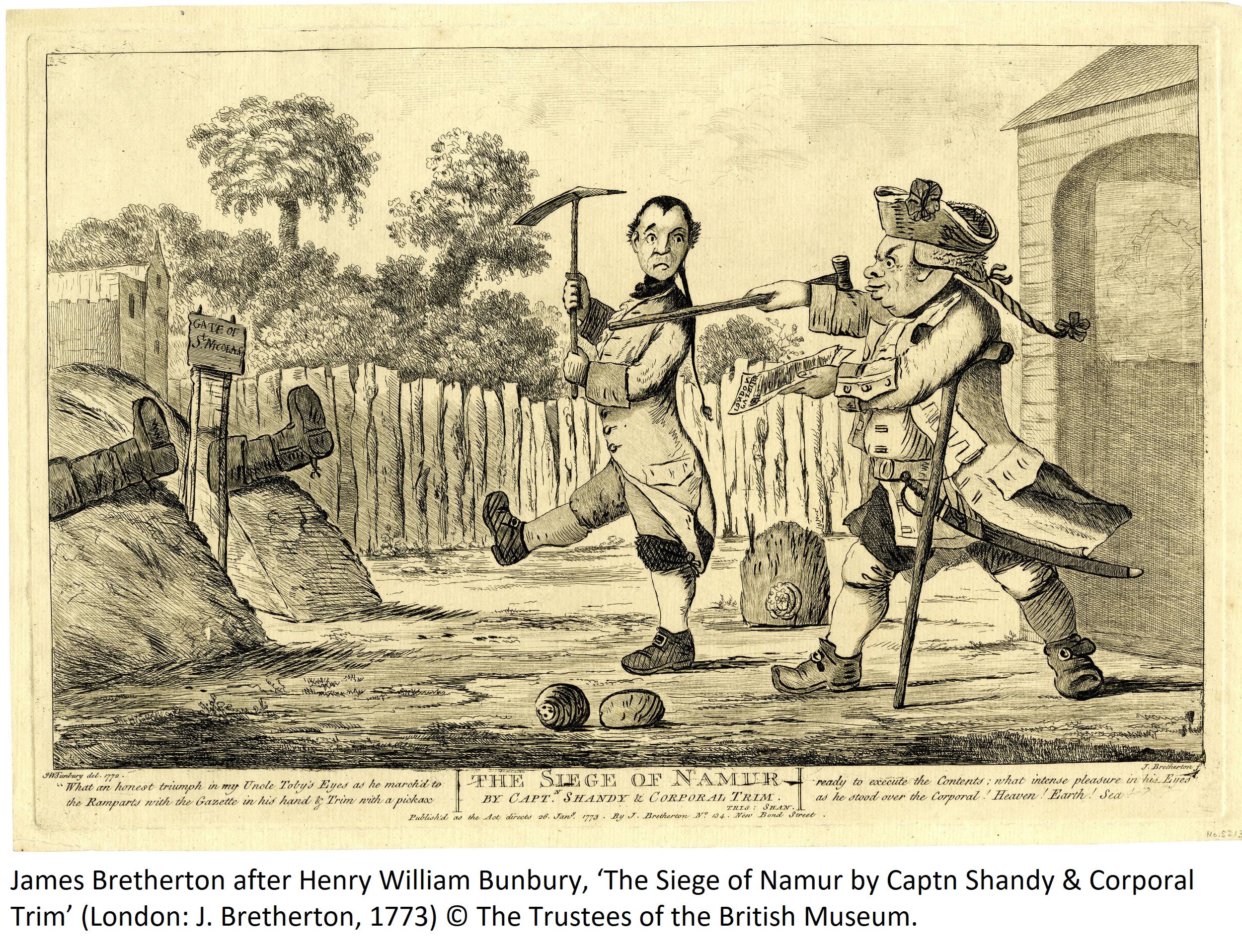

Social and occupational spheres were deeply intertwined in the music of Ignatius Sancho, who served as a butler under Lady Mary Churchill, Duchess of Montagu, and later as a valet to her son-in-law, George Brudenell, 4th Earl of Cardigan. Two of his extant dance collections are dedicated to members of the Brudenell family: Henry Scott, 3rd Duke of Buccleuch, who married George Brudenell’s daughter, Lady Elizabeth Montagu; and Elizabeth’s brother John, Marquis of Monthermer (Wright 1981). Sancho’s individual dance titles also reflect this relationship – Lady Mary Montagus Reel and Lord Dalkeiths Reel refer to Elizabeth's and Henry’s eldest daughter and son, while La Loge de Richmont, Richmond Hill and Dalkeith Palace denote Montagu property in Richmond and one of the Buccleuch estates in Scotland, which Sancho visited in 1770. It is notable that some of these dances were published several years after he had left the Brudenells’ employ. Sancho’s titles also  highlight sociable interactions and his enthusiasm for literature and theatre. His friendship with the caricaturist Henry William Bunbury and author Laurence Sterne plays out respectively in dances such as Trip to Barton, and Shandy Hall and Corporal Trim (Petchey [2019]). Sancho’s inclusion of multiple references to Sterne within his 1776 Cotillions &c. may have been an attempt to capitalise on the recent publication of their correspondence (Carretta 2015). Mungos Delight possibly serves as a double allusion to the character of Mungo from Charles Dibdin’s opera, The Padlock, and Sancho himself as a black man (Girdham 1997; Wright 1981).

highlight sociable interactions and his enthusiasm for literature and theatre. His friendship with the caricaturist Henry William Bunbury and author Laurence Sterne plays out respectively in dances such as Trip to Barton, and Shandy Hall and Corporal Trim (Petchey [2019]). Sancho’s inclusion of multiple references to Sterne within his 1776 Cotillions &c. may have been an attempt to capitalise on the recent publication of their correspondence (Carretta 2015). Mungos Delight possibly serves as a double allusion to the character of Mungo from Charles Dibdin’s opera, The Padlock, and Sancho himself as a black man (Girdham 1997; Wright 1981).

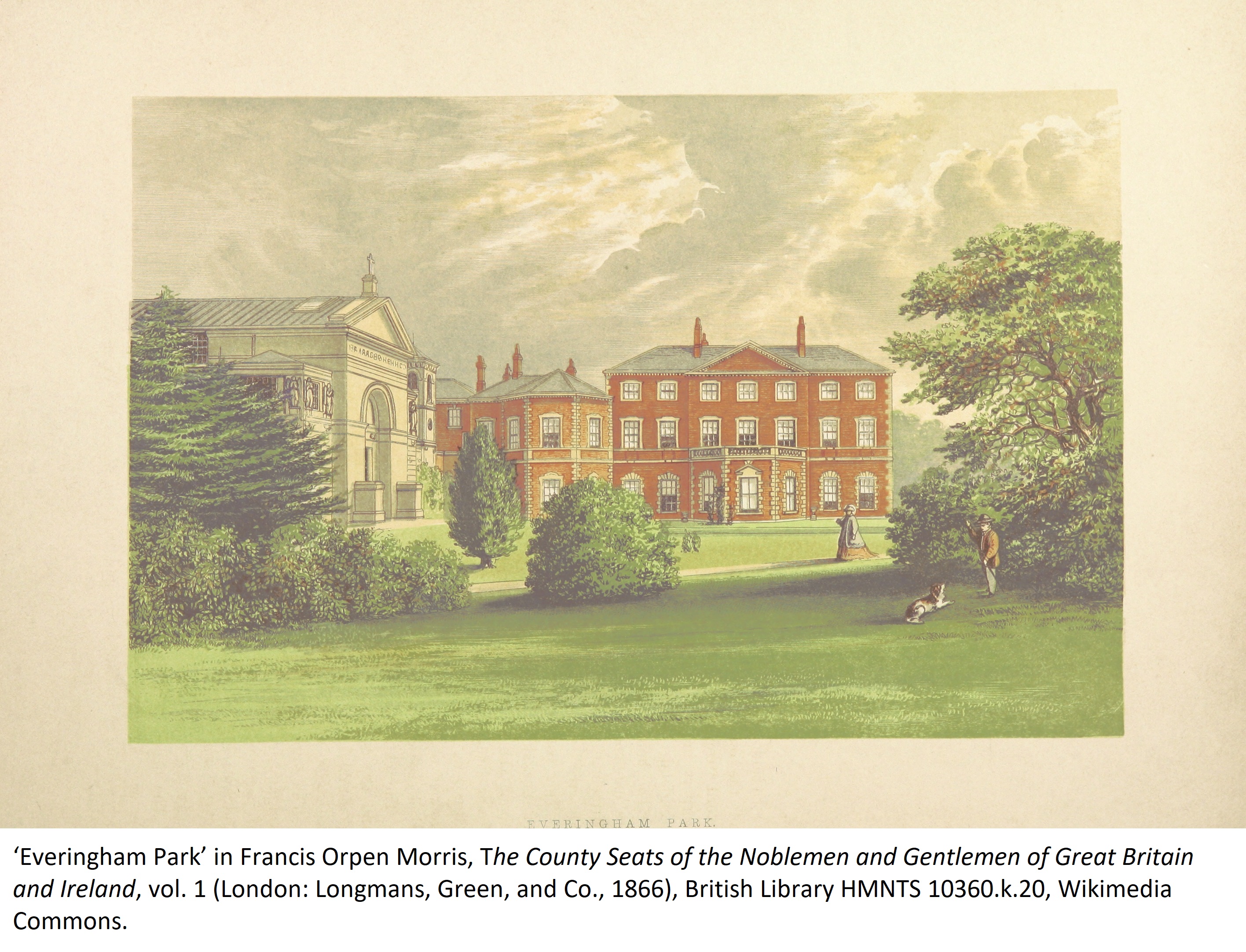

Sometimes, the inclusion of locations in dance titles points to a direct musical working relationship, a practice which went well into the nineteenth century. William Hardman’s A Collection of Three Waltzes, and Three Country Dances (1819) includes dances titled The York Winter Assemblies, Newby Hall and Woolley Park. Hardman was leader of the band at the York Winter Assemblies, but the ensemble was also engaged by Thomas Philip Robinson, 3rd Baron Grantham, to perform at a fete held at Newby Hall in October 1818. A month earlier a ball was held at Woolley Hall to celebrate the coming-of-age of Godfrey Wentworth and although none of the newspaper accounts mention the band, there is a distinct possibility that Hardman’s outfit was involved. It is highly likely that the Newby Hall and Woolley Park dances were composed for and performed in both houses. That Hardman specifically composed music for a particular event in a particular house is clear from an account of a ball at Everingham Park for which he expressly wrote the opening dance, titled Everingham Hall.  Hardman’s Collection was clearly published in response to the 1818-1819 Winter Assembly season in York, indicating not only that these dances were performed at the assemblies but illustrating how they migrated from one setting to another.

Hardman’s Collection was clearly published in response to the 1818-1819 Winter Assembly season in York, indicating not only that these dances were performed at the assemblies but illustrating how they migrated from one setting to another.

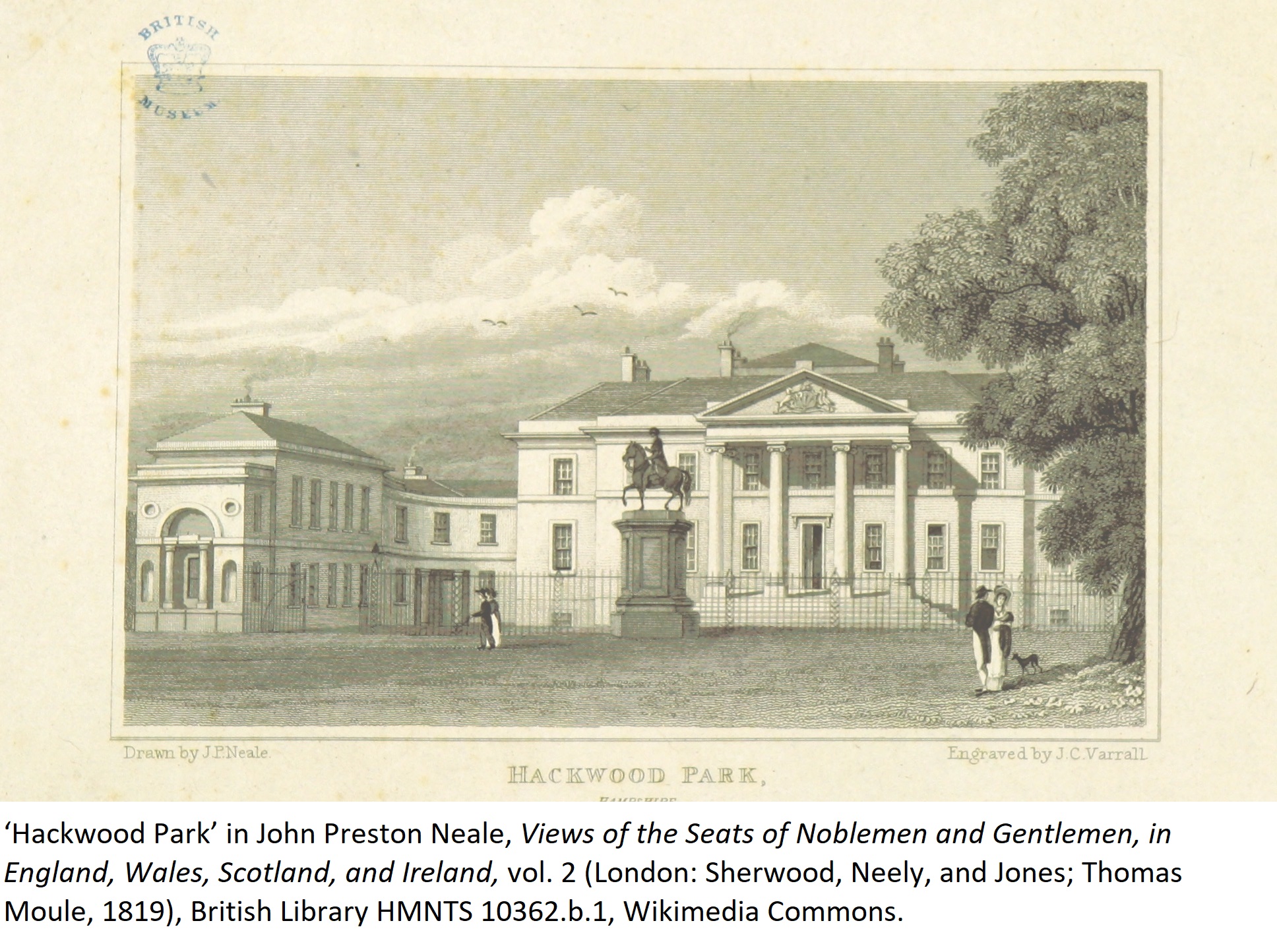

Naming dances after locations was also a way to attract business and reflect broader music-making activities at a local level. On 17 March 1849 the Reading Mercury inserted a short announcement regarding the publication of Henry Mills Powell’s The Hackwood Polka. After stating that it was “received with such marked enthusiasm at the two last Concerts given by the members of an Amateur Music Class at the Town-hall”, the paper also observed that “there is no doubt its local title, as well as its intrinsic excellence as a composition, will attract general interest in this neighbourhood, and insure [sic] for it an extensive and ready sale”. Powell was a violinist and later music seller who was engaged to direct a music class attached to the Basingstoke Mechanics Institute, on whose committee he served during the 1860s (Butler  2020; Sims 2010). Like the classes of other Institutes, the Basingstoke class was designed to “raise the musical character of the town…and increase the taste and excite a desire for the cultivation of that pleasing and useful science” (Hampshire Chronicle 21 February 1846). On 11 January 1849 the class gave a concert at the town hall as part of their series of public performances, which on this occasion was under the patronage of the Right Honourable Lady Bolton of Hackwood Park. The Hackwood Polka was dedicated to Lady Bolton and is an obvious response to her patronage of the entertainment. A copy of the score in the British Library indicates that one of the selling outlets was based in Basingstoke, thereby ensuring local coverage. Powell’s own activities collectively as teacher, composer, performer, music seller and sometime agent surely contributed much to the Institute’s endeavours (Sims 2010).

2020; Sims 2010). Like the classes of other Institutes, the Basingstoke class was designed to “raise the musical character of the town…and increase the taste and excite a desire for the cultivation of that pleasing and useful science” (Hampshire Chronicle 21 February 1846). On 11 January 1849 the class gave a concert at the town hall as part of their series of public performances, which on this occasion was under the patronage of the Right Honourable Lady Bolton of Hackwood Park. The Hackwood Polka was dedicated to Lady Bolton and is an obvious response to her patronage of the entertainment. A copy of the score in the British Library indicates that one of the selling outlets was based in Basingstoke, thereby ensuring local coverage. Powell’s own activities collectively as teacher, composer, performer, music seller and sometime agent surely contributed much to the Institute’s endeavours (Sims 2010).

Changing Identities

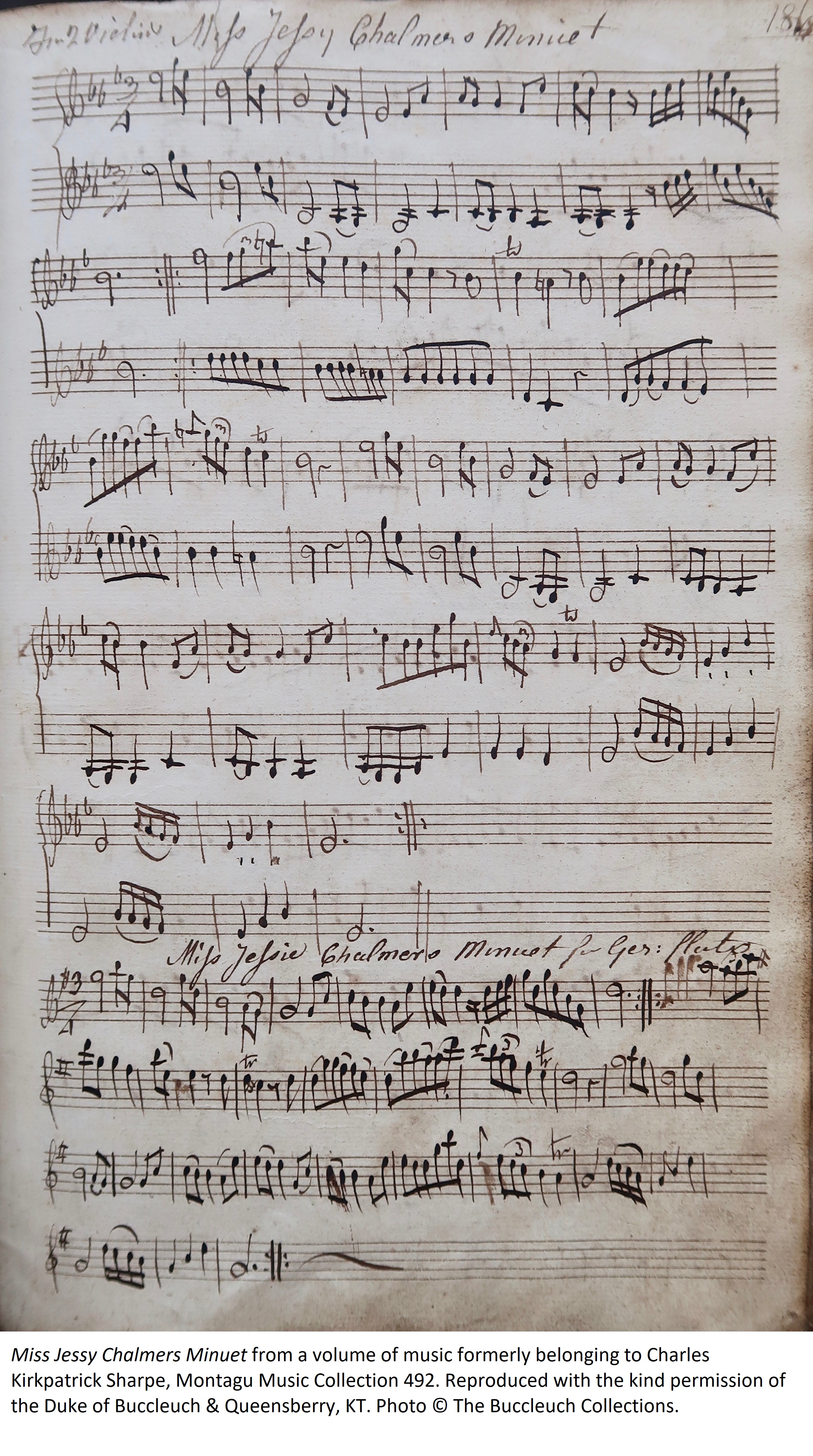

Amongst published collections of dances, it wasn’t unusual for a given dance tune to be known by more than one name. Dances bearing the names of girls were often changed after they married. In the preface to his 1836 edition of Minuets &c by Thomas Alexander Erskine, 6th Earl of Kelly, the antiquary Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe articulated this practice. Listing brief genealogical descriptions of the ladies after whom many of the minuets were named, he noted where the dances were presented before their marriage or bore their maiden names in the original manuscript material from which his publication was derived. Examples include Miss Jessy Chalmers Minuet which became Mrs Cumming’s Minuet, and The Duchess of Gordon’s Minuet, which was previously titled Miss Jeanie Maxwell’s Minuet, both of which are present in Sharpe’s own music collection (Johnson 2005).

Alterations in dance titles also occurred in relation to theatrical works. The New Dance Fan for 1797 featured a country dance called Little Peggy’s Love after a ballet of the same name produced at the King’s Theatre in 1796. The role of Peggy was danced by Madame Hilligsberg, at whose benefit performance the ballet premiered, leading to the same tune being published as Mad.m Hillisberg’s Reel in Cahusac & Sons’s Twenty Four Country Dances for the Year 1798. Another ballet staged the same year, this time at Drury Lane, was The Scotch Ghost, or Little Fanny’s Love, starring Signora Bossi del Caro in the role of Fanny. The ballet incorporated the tune of Lady Baird’s Fancy, which had already been published by Preston & Son (1792) and Thomas Cahusac (1794) in their respective collections of twenty-four and twelve country dances. In Thompson’s Twenty four Country Dances for 1799 the tune was reproduced as Madam Bossi’s Fancy.

Alterations in dance titles also occurred in relation to theatrical works. The New Dance Fan for 1797 featured a country dance called Little Peggy’s Love after a ballet of the same name produced at the King’s Theatre in 1796. The role of Peggy was danced by Madame Hilligsberg, at whose benefit performance the ballet premiered, leading to the same tune being published as Mad.m Hillisberg’s Reel in Cahusac & Sons’s Twenty Four Country Dances for the Year 1798. Another ballet staged the same year, this time at Drury Lane, was The Scotch Ghost, or Little Fanny’s Love, starring Signora Bossi del Caro in the role of Fanny. The ballet incorporated the tune of Lady Baird’s Fancy, which had already been published by Preston & Son (1792) and Thomas Cahusac (1794) in their respective collections of twenty-four and twelve country dances. In Thompson’s Twenty four Country Dances for 1799 the tune was reproduced as Madam Bossi’s Fancy.

A more daring exchange took place with William Napier’s publication of The Favourite Minuets Perform’d at the Fetè Champêtre in 1774. The event in question was held to celebrate the approaching nuptials of Edward Smith Stanley, future 12th Earl of Derby and Lady Elizabeth (Betty) Hamilton, daughter of the 6th Duke of Hamilton and the subsequent Duchess of Argyll. The minuets were ostensibly “composed on the occasion” by Kelly; however, they are in fact a recycling of his previous compositions, some of which appear under different names. Many of the minuets appear in Neil Stewart’s A Collection of the Newest and Best Minuets, which went through several editions in the 1760s and 1770s. While some of Kelly’s minuets retained the same or similar names across both publications, others were crucially altered to reflect the fête champêtre: Mrs Grant of Arndilly’s Minuet became Genl Burgoine’s Minuet; Mrs Cuming’s Minuet morphed into Lord Stanley’s Minuet; and The Dutches of Beuccleugh’s Minuet appeared as The Fete Champetre Minuet (Johnson 2005). Lady Wallace of Craigie’s Minuet from Sharpe’s publication was titled the Dutchess of Gordon’s Minuet in Napier’s version; Lady Wallace was the sister of the Duchess of Gordon, a connection more apparent in Stewart’s collection where the minuet was called Miss Eglington Maxwell’s Minuet. The deliberate retitling of Kelly’s minuets not only got him out of having to do much work, the masking effect matched the theatrical nature of the occasion. As shown by such interchangeability, the names of dances were often a way of identifying tunes and describing context, rather than defining anything specific about the music itself.