Ignatius Sancho: A Black Dance Composer

“pray make my kindest respects to your good partner, and tell him, I think I have a right to trouble him with my musical nonsense”

(Ignatius Sancho to Mrs H---, 17 June 1779)

Eighteenth-century Britain was home to thousands of free and enslaved black people, who arrived from Africa and British colonies across the Atlantic as children, servants, merchants and military personnel. Amongst them were black musicians, who filled a variety of roles within British cultural life. Street entertainers like Joseph Johnson and Billy Waters, who had both served in the navy, were effectively reduced to employing their craft to beg. Black military bandsmen were often trumpeters and drummers, and were employed in particular to play Janissary instruments, a practice that highlighted British society’s view of them as exotic ornaments, similarly documented in the manner in which black servants were portrayed in aristocratic households (Pickering 1990; Wright 1986). Artists such as Joseph Emidy and George Polgreen Bridgetower made significant contributions to public concert life, the former being kidnapped to serve as a ship’s dance musician before settling in Cornwall as a violinist, composer, teacher of various instruments and tuner (Girdham 1996; McGrady 1986). Occasional references to female musicians indicate that some black women sang, including in their trade as prostitutes or on stage in productions such as John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (Fryer 2018). Visual representations of public music-making also incorporated black musicians: William Hogarth’s Southwark Fair, for instance, shows a black boy striding along with a trumpet; John June’s A View of Cheapside features a stand of musicians including a black horn player; and Charles Loraine Smith in The Country Concert depicts a black military musician (Dabydeen 1987). Each is conspicuous by being the only black musician amongst their surroundings.

Eighteenth-century Britain was home to thousands of free and enslaved black people, who arrived from Africa and British colonies across the Atlantic as children, servants, merchants and military personnel. Amongst them were black musicians, who filled a variety of roles within British cultural life. Street entertainers like Joseph Johnson and Billy Waters, who had both served in the navy, were effectively reduced to employing their craft to beg. Black military bandsmen were often trumpeters and drummers, and were employed in particular to play Janissary instruments, a practice that highlighted British society’s view of them as exotic ornaments, similarly documented in the manner in which black servants were portrayed in aristocratic households (Pickering 1990; Wright 1986). Artists such as Joseph Emidy and George Polgreen Bridgetower made significant contributions to public concert life, the former being kidnapped to serve as a ship’s dance musician before settling in Cornwall as a violinist, composer, teacher of various instruments and tuner (Girdham 1996; McGrady 1986). Occasional references to female musicians indicate that some black women sang, including in their trade as prostitutes or on stage in productions such as John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (Fryer 2018). Visual representations of public music-making also incorporated black musicians: William Hogarth’s Southwark Fair, for instance, shows a black boy striding along with a trumpet; John June’s A View of Cheapside features a stand of musicians including a black horn player; and Charles Loraine Smith in The Country Concert depicts a black military musician (Dabydeen 1987). Each is conspicuous by being the only black musician amongst their surroundings.

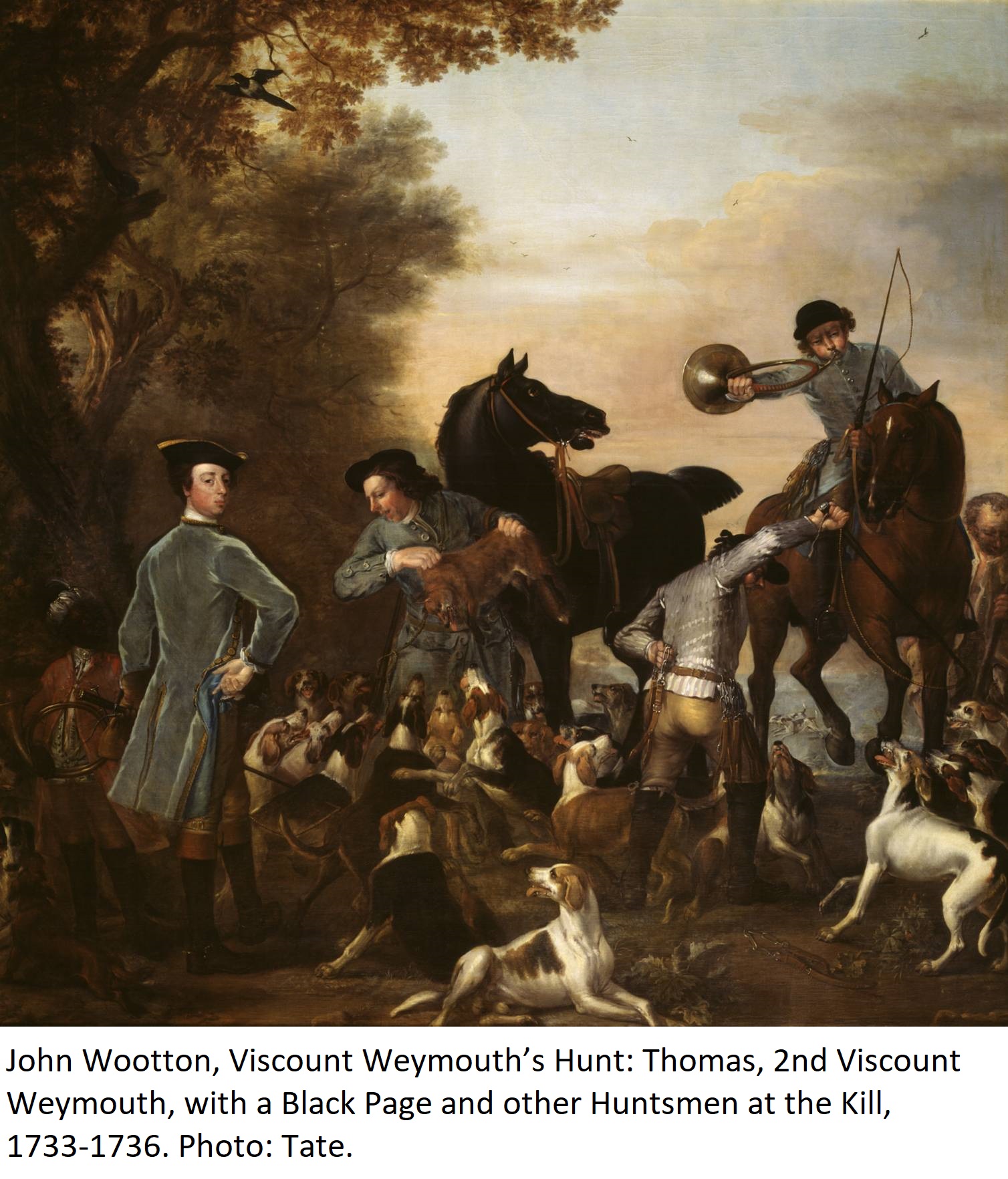

Numerous newspaper notices for enslaved runaways in Britain and America – “wanted” notices to all intents and purposes – attest to their musical ability as a feature that marked them out and made them publicly visible, as they would have been inclined to use their skill to make a living. Musical abilities, then, were a blessing and a curse. The instruments featured in the notices included violin, French horn, tabor & pipe, trumpet, drum, flute and fife (Winans 2018). In some cases it is clear that musical education was provided by masters and mistresses, used at times to prove that black people could acquire refined skills: William Franklin’s slave, King, ran away from London and was taken in by a lady who provided him with tuition on the French horn and violin, which appeared in a later runaway notice; Julius Soubise, protégé of Catherine Douglas, Duchess of Queensberry, played the violin, “composed several musical pieces in the Italian style, and sang them with a comic humour that would have fitted him for a primo buffo at the Opera-house” (Angelo 1830, 449); and the oboist William Parke taught a black servant to General Charles O’Hara at the latter’s instigation (Parke 1830). The abolitionist Olaudah Equiano, however, eventually learned how to play the horn from a neighbour in London, taking “great delight in blowing on this instrument” after it was first mooted during his naval service (Equiano 1794, 241). Such musical skill would have been virtually obligatory in the case of huntsmen, and perhaps also coachmen. Charles Cato, a black footman who was passed on as a present to the Prince of Wales in 1738 and who was apparently depicted in a hunting scene by John Wootton, was “reckon’d to blow the best French Horn and Trumpet in England” (Hore 1895; Talbot 2017, 254). Sometimes the value of such servants was more cultural than pragmatic: Richard Barry, 7th Earl of Barrymore, appeared with a hunting retinue which included “four Africans, superbly mounted, and superbly

Numerous newspaper notices for enslaved runaways in Britain and America – “wanted” notices to all intents and purposes – attest to their musical ability as a feature that marked them out and made them publicly visible, as they would have been inclined to use their skill to make a living. Musical abilities, then, were a blessing and a curse. The instruments featured in the notices included violin, French horn, tabor & pipe, trumpet, drum, flute and fife (Winans 2018). In some cases it is clear that musical education was provided by masters and mistresses, used at times to prove that black people could acquire refined skills: William Franklin’s slave, King, ran away from London and was taken in by a lady who provided him with tuition on the French horn and violin, which appeared in a later runaway notice; Julius Soubise, protégé of Catherine Douglas, Duchess of Queensberry, played the violin, “composed several musical pieces in the Italian style, and sang them with a comic humour that would have fitted him for a primo buffo at the Opera-house” (Angelo 1830, 449); and the oboist William Parke taught a black servant to General Charles O’Hara at the latter’s instigation (Parke 1830). The abolitionist Olaudah Equiano, however, eventually learned how to play the horn from a neighbour in London, taking “great delight in blowing on this instrument” after it was first mooted during his naval service (Equiano 1794, 241). Such musical skill would have been virtually obligatory in the case of huntsmen, and perhaps also coachmen. Charles Cato, a black footman who was passed on as a present to the Prince of Wales in 1738 and who was apparently depicted in a hunting scene by John Wootton, was “reckon’d to blow the best French Horn and Trumpet in England” (Hore 1895; Talbot 2017, 254). Sometimes the value of such servants was more cultural than pragmatic: Richard Barry, 7th Earl of Barrymore, appeared with a hunting retinue which included “four Africans, superbly mounted, and superbly  dressed in scarlet and silver, who were correct performers on the French horn; and who occasionally, in the woods and the vallies [sic], gladdened Diana with Handel’s harmony” (Pasquin 1793, 102).

dressed in scarlet and silver, who were correct performers on the French horn; and who occasionally, in the woods and the vallies [sic], gladdened Diana with Handel’s harmony” (Pasquin 1793, 102).

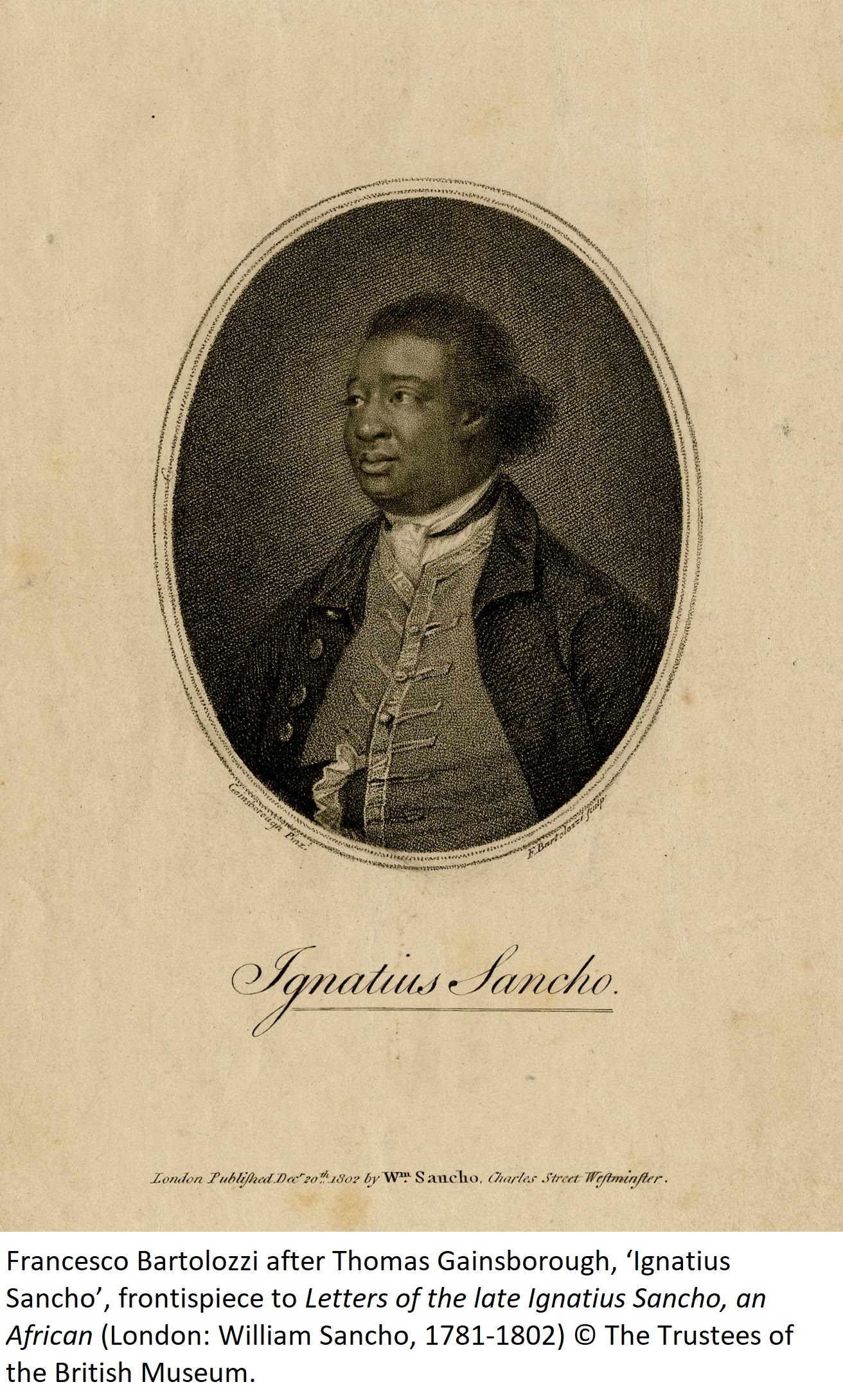

One black servant who emerged with musical skill was Ignatius Sancho (1729?-1780), who by the late eighteenth century would become one of London’s best-known black residents. His early history, based largely on Joseph Jekyll's The Life of Ignatius Sancho, is sketchy and difficult to verify, but he was seemingly born into slavery and brought to England as a small child (Carey 2003). His education was supported by John, 2nd Duke of Montagu and after the Duke’s death in 1749, Sancho served as a butler in the Montagu household and later became valet to the Duke’s son-in-law, George Brudenell, 4th Earl of Cardigan (Carretta 2015). The details of Sancho’s musical education remain unknown, but it almost certainly took place via the Montagu household: John Montagu supported French and Italian comedians and dancers at the Haymarket Theatre; he was one of the early directors of the Royal Academy of Music, founded in 1719 to support Italian opera in London; and he was responsible for the preparations for staging Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks in celebration of the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1749 (Deutsch 1955; Scott 2016). Handel was also a guest for lunch at Montagu House in 1747. Documents in the Montagu family archives reveal glimpses of the musical education afforded to other servants under John Montagu’s aegis. The violinist Pietro Castrucci, who was leader of the Royal Academy orchestra, was hired to teach “ye Black Boy” in the 1720s while two decades later a Joseph Abington was employed to teach music and the violin to two members of the household who were likely to be black (Boucher 2019).

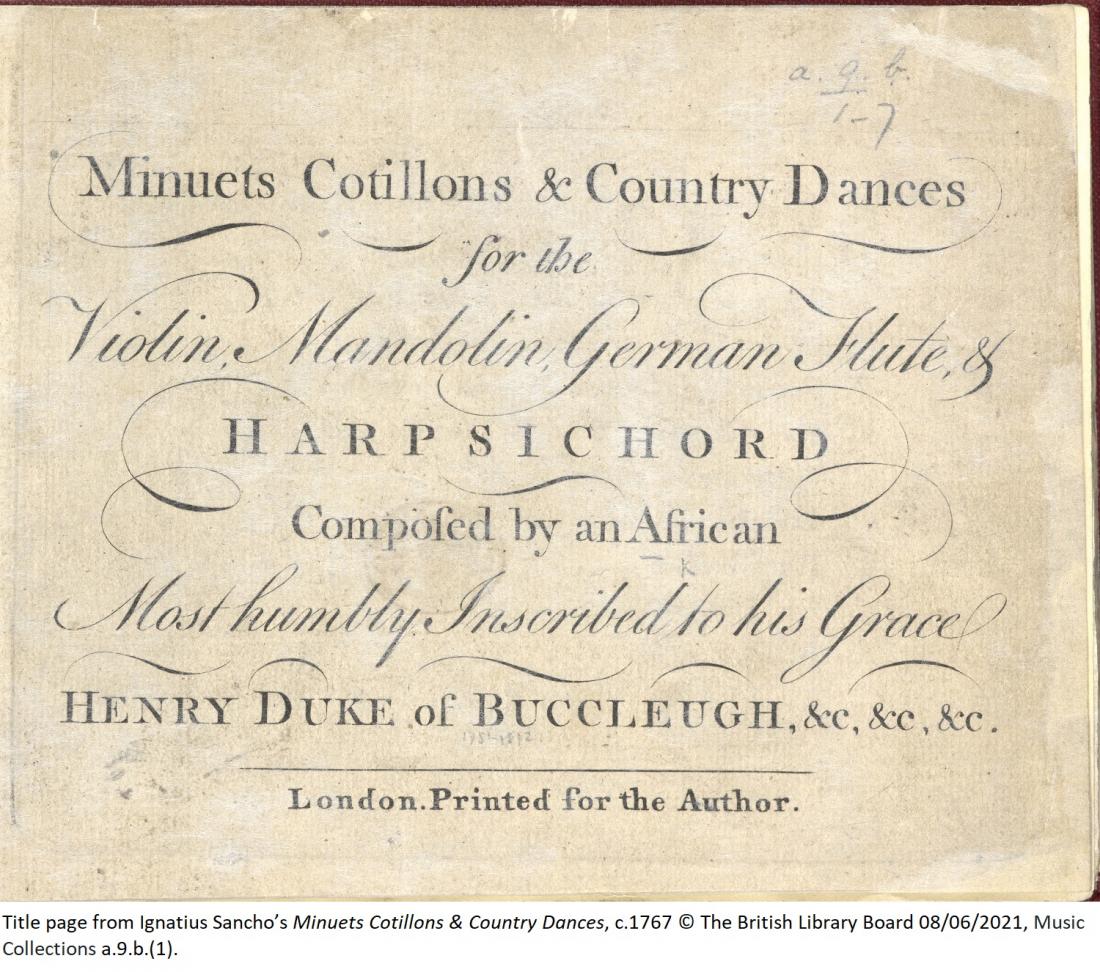

Sancho stands out from several of the black musicians already mentioned as his employment wasn’t obviously contingent on his musical abilities and he was also a composer who published for a white genteel market. He produced at least four volumes of dances and a collection of songs. In the earlier publications he appeared on the title page simply as “an African”, a term he used often when referring to himself in his letters; this drew on the exoticisation of black people and the unfamiliarity of a black composer for marketing purposes, whilst simultaneously erasing his own name. Two of his dance volumes, both containing minuets, are dedicated to members of his employer’s family: George Brudenell’s son, John, Marquis of Monthermer; and George’s son-in-law, Henry Scott, 3rd Duke of Buccleuch. Several of Sancho’s dances refer to other family members and properties, as well as Sancho’s own acquaintances (Petchey [2019]; Wright 1981). His use of the mandolin on the title pages of the minuets is rooted in familiarity with the Montagu-Brudenell family’s music-making. The Neapolitan mandolin became fashionable in Britain in the 1760s and was played in concert performances, operas and within miscellaneous variety entertainments. With four courses of strings, it shared the same tuning as the violin, which facilitated both writing for the instrument by composers familiar with the latter and the marketability of the music. Lord Monthermer travelled to Naples in the mid-to-late 1750s as part of his Grand Tour and his 1758 portrait by Pompeo Batoni shows him with a Neapolitan mandolin tucked under his arm and a copy of one of Arcangelo Corelli’s sonatas (Scott 2016; Sparks 2018). This may have been the same mandolin that Sancho was selling from his grocery shop in Westminster some years after Lord Monthermer’s death (Public Advertiser 16 April 1776) – the instrument was made by Donatus Filano, one of the finest exponents of Neapolitan mandolin craft. Given his service role within the Montagu family, it is highly likely that Sancho was aware of preparations for balls such as that given at Montagu House in 1764, which may have included exposure to the band engaged for the occasion (Brooks 2019). Such events may have reinforced his formal musical education by providing opportunities for incidental listening, but they may also have featured his own compositions.

Sancho stands out from several of the black musicians already mentioned as his employment wasn’t obviously contingent on his musical abilities and he was also a composer who published for a white genteel market. He produced at least four volumes of dances and a collection of songs. In the earlier publications he appeared on the title page simply as “an African”, a term he used often when referring to himself in his letters; this drew on the exoticisation of black people and the unfamiliarity of a black composer for marketing purposes, whilst simultaneously erasing his own name. Two of his dance volumes, both containing minuets, are dedicated to members of his employer’s family: George Brudenell’s son, John, Marquis of Monthermer; and George’s son-in-law, Henry Scott, 3rd Duke of Buccleuch. Several of Sancho’s dances refer to other family members and properties, as well as Sancho’s own acquaintances (Petchey [2019]; Wright 1981). His use of the mandolin on the title pages of the minuets is rooted in familiarity with the Montagu-Brudenell family’s music-making. The Neapolitan mandolin became fashionable in Britain in the 1760s and was played in concert performances, operas and within miscellaneous variety entertainments. With four courses of strings, it shared the same tuning as the violin, which facilitated both writing for the instrument by composers familiar with the latter and the marketability of the music. Lord Monthermer travelled to Naples in the mid-to-late 1750s as part of his Grand Tour and his 1758 portrait by Pompeo Batoni shows him with a Neapolitan mandolin tucked under his arm and a copy of one of Arcangelo Corelli’s sonatas (Scott 2016; Sparks 2018). This may have been the same mandolin that Sancho was selling from his grocery shop in Westminster some years after Lord Monthermer’s death (Public Advertiser 16 April 1776) – the instrument was made by Donatus Filano, one of the finest exponents of Neapolitan mandolin craft. Given his service role within the Montagu family, it is highly likely that Sancho was aware of preparations for balls such as that given at Montagu House in 1764, which may have included exposure to the band engaged for the occasion (Brooks 2019). Such events may have reinforced his formal musical education by providing opportunities for incidental listening, but they may also have featured his own compositions.

Despite Sancho’s dances being firmly rooted in the traditions of the white aristocratic class, it is important to consider them within the context of black dance and his own connections with black musicians. References to black balls in late eighteenth-century London are scant but a description in the London Chronicle on 16-18 February 1764 is revealing:

Among the sundry fashionable routs or clubs, that are held in town, that of the Blacks or Negro servants is not the least. On Wednesday night last, no less than fifty-seven of them, men and women, supped, drank, and entertained themselves with dancing and music, consisting of violins, French horns, and other instruments, at a public-house in Fleet-street, till four in the morning. No Whites were allowed to be present, for all the performers were Blacks.

This was repeated almost verbatim in the London Evening Post on 12-15 June 1773, with minor alterations to the text. It is clear that various social options were available for black people to engage with dance: Jack Beef, servant to John Baker (former Solicitor-General for the Leeward Islands) attended black balls; Francis Barber, servant to Samuel Johnson, went with his white wife to an annual “little dance and supper, to divert our servants and their friends” held by Hester Piozzi in celebration of Johnson’s birthday (Gerzina 1995, 49), while “Miss Sarah S – dd – ns”, a prostitute advertised in Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies in 1788 partook of  “black hops” (Fryer 2018, 81).

“black hops” (Fryer 2018, 81).

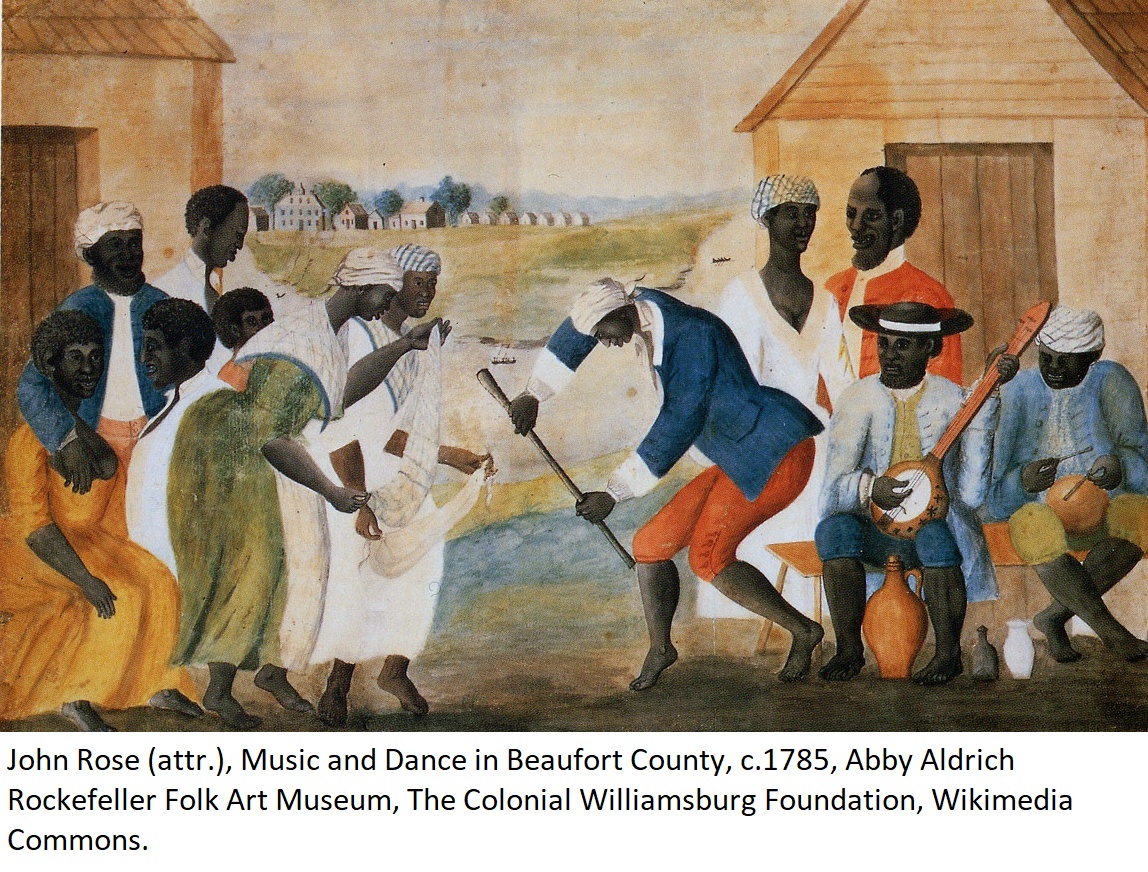

Given the trade routes between the Caribbean, America and England, it is possible that black dance musicians in London were influenced by the experience of dance across the Atlantic. It is clear that black musicians there played both for white balls and for their own dances. Descriptions of dancing indicate the coexistence of European and African instruments in providing accompaniment, some of which may have been transported on slave ships (Epstein 1977; Jamison 2003). Overwhelmingly, the fiddle was the primary instrument adopted by black musicians, but the banjo was also described by a number of writers (Southern 1997; Wells 2003). John Ferdinand Dalziel Smyth observed a banjo and quaqua (a percussion instrument) played at a black dance in Virginia; subscribers to his publication, A Tour in the United States of America (1784), included Henry Scott and George Brudenell. The banjo and quaqua were just two of eighteen musical instruments listed by John Gabriel Stedman in Surinam in the 1770s, the former of which he described as “like a mandoline or guitar” (Stedman 1796, 287). Many of the instruments Stedman described are percussive, although he also included flutes. In Antigua in 1788 John Luffman wrote of the toombah which was “similar to the tabor, and has gingles of tin or shells”. Three years later, Sir William Young described Christmas festivities on the island of St Vincent in which he opened a ball with “black Phillis” by dancing a minuet to the sound of two fiddles and a “tamborin” (Epstein 1977, 36, 83).

Sancho was too young when he arrived in England to have consciously learned this heritage, but London was home to many black people who knew their African roots and/or who grew up on plantations with its associated culture. In recounting the music of his homeland, Olaudah Equiano mentioned “drums of different kinds, a piece of music which resembles a guitar, and another much like a stickado”, knowledge that went alongside his ability on the French horn (Equiano 1794, 8). Sancho knew Julius Soubise and Charles Lincoln, who was part of a band of music on board the ship that took Soubise out to India in the face of rape allegations (Carretta 2015). It is difficult to imagine that he wasn’t further acquainted with other military musicians, either those stationed in England or those who had served abroad. All of this raises questions about whether any of Sancho’s music was ever performed by black musicians and how much black dance music in Britain was influenced by African culture. Certainly, whilst Sancho’s inclusion of violins and French horn parts in some of his minuets followed conventional scoring, it also makes it possible that both black and white musicians could have played his music. Did the “other instruments” at the 1764 black ball in Fleet street include anything like a guitar or mandolin, or the drums, fifes and percussion instruments that were the preserve of black military bandsmen? A runaway notice in the General Advertiser on 31 May 1751 for “an old Negro Fellow” by the name of Quao, who “plays upon an Instrument call’d in his Country, The Banger [banjo]” seems to indicate that some version of the instrument was known in England and therefore may also have been included in dance music. And what of Sancho’s own musical abilities – was he a horn player, a violinist, or even a mandolinist?

While it is rather telling that we have little information on these questions, Sancho’s musical legacy nonetheless lived on through his family. After his death, Elkanah Watson paid a visit to his widow and heard one of Sancho’s daughters on the harpsichord, accompanied by a white man “singing with her in concert”. He spent “a pleasant hour in conversation, interspersed with singing and music”, as perhaps happened often in the Sancho household (Watson 1856, 233).

Compositions by Ignatius Sancho

Minuets Cotillons & Country Dances for the Violin, Mandolin, German Flute, & Harpsichord Composed by an African Most humbly Inscribed to his Grace Henry Duke of Buccleugh. c.1767. London: Printed for the Author. British Library Music Collections a.9.b.(1.). https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/minuets-cotillons-and-country-dances-by-ignatius-sancho

A Collection New Songs Composed by An African Humbly Inscribed to the Honble Mrs James Brudenell. c.1769. [London?]: The Author. British Library Music Collections H.1652.f.(31.).

Minuets &c. &c. for the Violin Mandolin German-Flute and Harpsichord. Compos’d by an African. Book 2d. Humbly Inscribed to the Right Honble John Lord Montagu of Boughton. c.1770. London: Printed for the Author, sold by Richard Duke. British Library Music Collections b.53.b.(1.). Copy available https://imslp.org/wiki/Minuets%2C_etc._(Sancho%2C_Ignatius)

Cotillions &c. Humbly Dedicated (with Permission) To The Princess Royal. By Her Royal Highness’s Most Obedient Servant Ignatius Sancho. 1776. London: C & S. Thompson. Houghton Library, Harvard University, Theatre Collection GEN TS 552.15.14.21. https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:489989698$1i

Twelve Country Dances for the Year 1779. Set for the Harpsichord By Permission Humbly Dedicated to the Right Honourable Miss North, by her most obedient Servant Ignatius Sancho. 1779. London: S and A Thompson. Library of Congress M30 .S25 (Case). Copy available https://imslp.org/wiki/12_Country_Dances_(Sancho%2C_Ignatius)

Further references to black dance and dance music can be found under Further Resources.