Dance and Luxury: Showing off the House

Newspaper descriptions of balls in the early nineteenth century show close links between dance and narratives of splendour and luxury. They are heavy with the weight of social rank, and riddled with references to costly fabrics and jewels. Lengthier descriptions frequently emphasise two aspects: the luminosity of the decorations and the space in which a ball takes place; and the delicacy and richness of the food supplied. In this sensuous and multi-sensory experience, at least as it is depicted through print, dance emerges as a conduit, or perhaps even a ruse, for the display of luxurious consumerism.

Personal descriptions offer more detailed insights into the practicalities of ball organisation, the choices to be made, and the strategic invocation of luxury. In December 1791 Frances Bankes wrote to her mother-in-law meticulously outlining the arrangements for a ball she held at Kingston Lacy after recent alterations to the house. Recounting how the various rooms were used, Frances’s comments also indicate the importance of material display. The “red Damask Bed with the Satin wood Bedposts” was moved to “the Apartment the most seen”, and she remarked gratifiedly “you cannot imagine how well it looked that night”. The use of candles in the home to provide artificial lighting was a luxury only the well-off could afford (Stobart and Rothery 2016). Frances employed twenty in each supper room, again with an eye for presentation: “I am persuaded the money bestowed upon Lamps and Candles at an Entertainment of this kind makes infinitely more show than if you spend the same sum in any other way” (Cleminson 1991, 406-407).

Personal descriptions offer more detailed insights into the practicalities of ball organisation, the choices to be made, and the strategic invocation of luxury. In December 1791 Frances Bankes wrote to her mother-in-law meticulously outlining the arrangements for a ball she held at Kingston Lacy after recent alterations to the house. Recounting how the various rooms were used, Frances’s comments also indicate the importance of material display. The “red Damask Bed with the Satin wood Bedposts” was moved to “the Apartment the most seen”, and she remarked gratifiedly “you cannot imagine how well it looked that night”. The use of candles in the home to provide artificial lighting was a luxury only the well-off could afford (Stobart and Rothery 2016). Frances employed twenty in each supper room, again with an eye for presentation: “I am persuaded the money bestowed upon Lamps and Candles at an Entertainment of this kind makes infinitely more show than if you spend the same sum in any other way” (Cleminson 1991, 406-407).

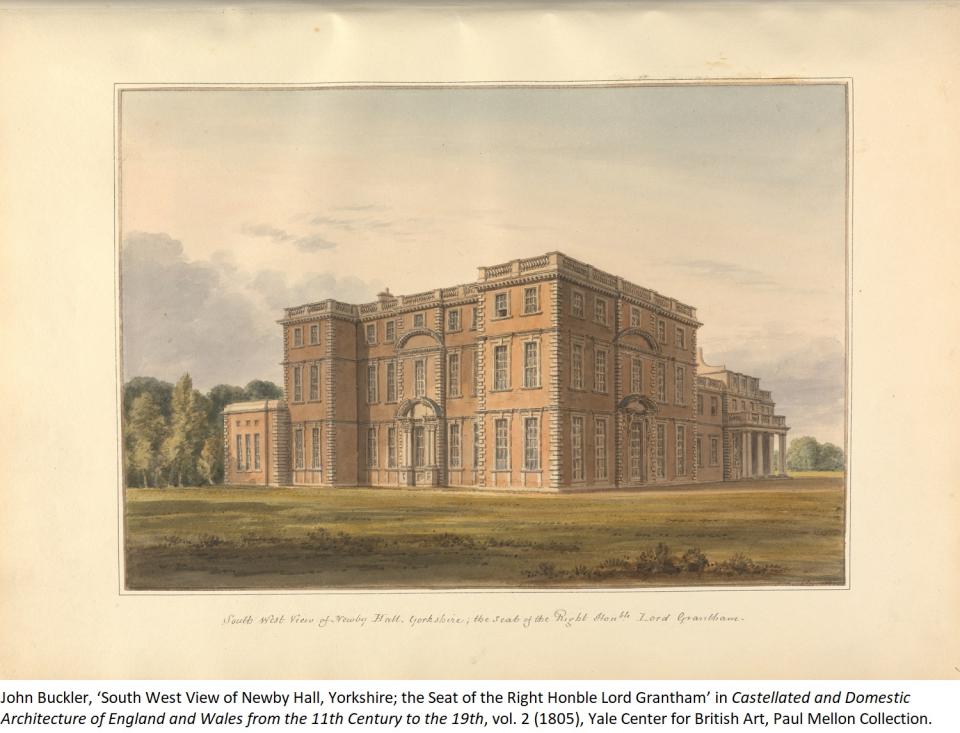

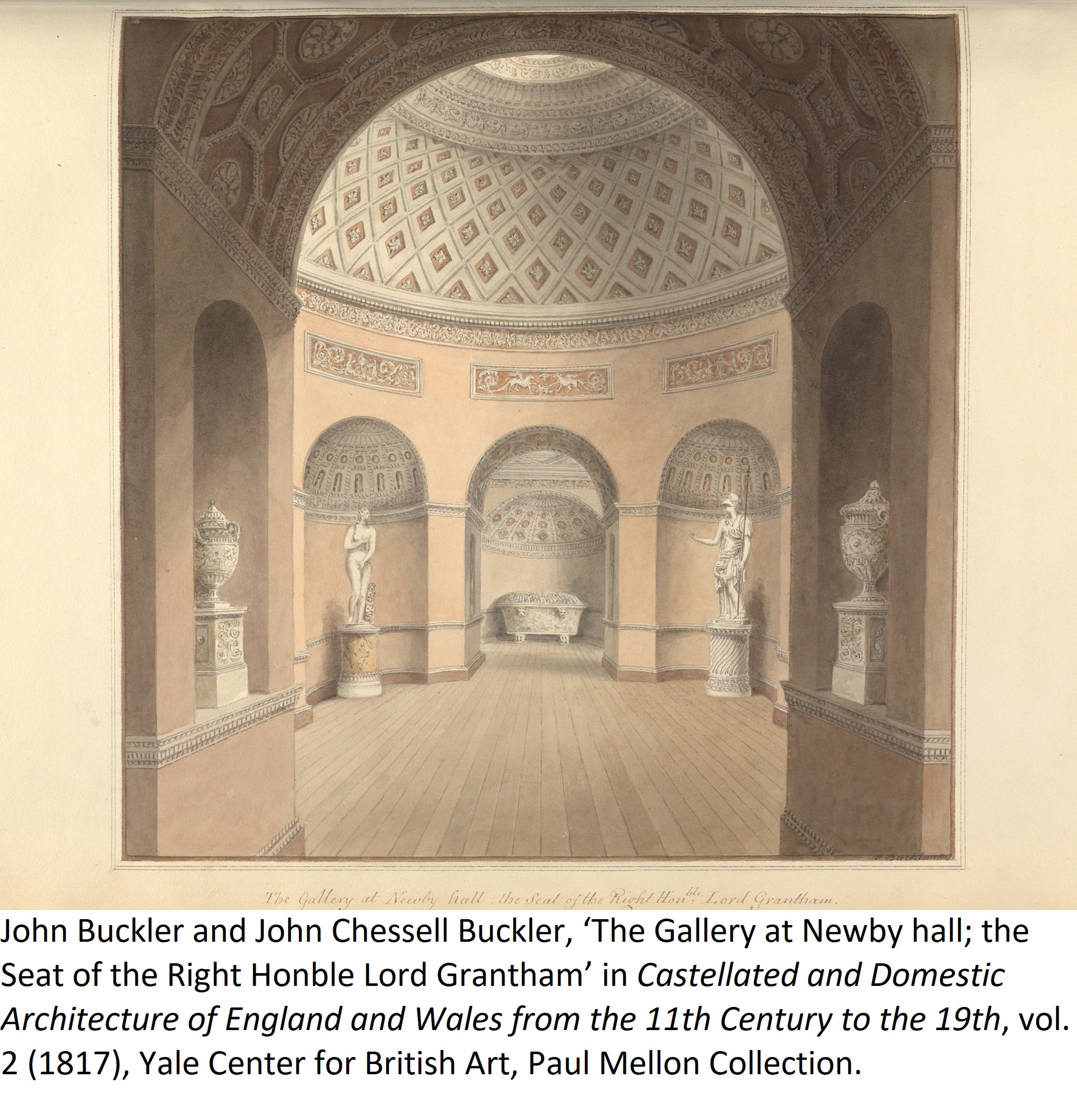

Two balls hosted by Thomas Philip Robinson, 3rd Baron Grantham and his wife, Henrietta Frances Cole, illustrate the various means through which wealth and luxury were exhibited. In October 1818, Lord Grantham held a ball at his country seat of Newby Hall. Although less extravagant than London’s most resplendent balls – a modest 180 guests or so, including the Yorkshire Hussars regiment – it nevertheless gave him the chance to show off Newby’s gems. The house was remodelled by his predecessor, William Weddell, in the 1760s and featured the neo-classical work of Robert Adam, Joseph Rose and Antonio Zucchi. Lord Grantham related the ball in a letter to his mother, giving her almost a virtual tour of the house. The exterior was “brilliantly illuminated with colored lamps forming Stars & festoons” so that the “architectural Lines of the House” were accentuated. Guests were received in the library, the ceiling of which was covered with Rose’s handiwork, and a vestibule contained “two temporary Conservatories… fitted with what the newspapers woud [sic] call choice Exotics”. But the star of the splendour was Adam’s statue gallery, designed to house Weddell’s superb collection of Roman antiquities. Repurposed as a supper room, the gallery was “as light as lamps could make it, & with the Gold Plate arranged on the large Sarcophagus at the end looked very singular & striking” (Bedfordshire Archives L30/13/22/13).

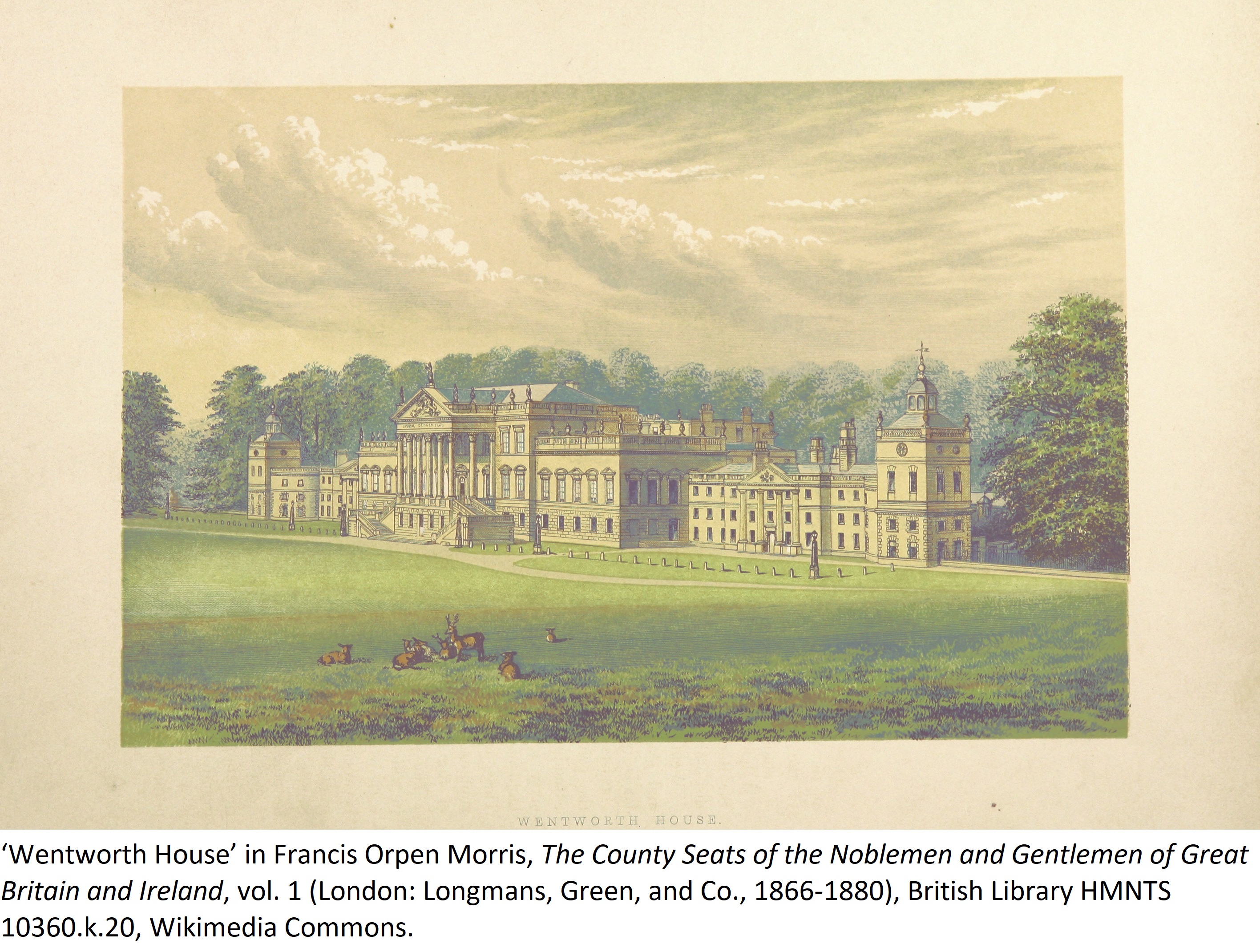

Lord Grantham’s account mirrors the manner in which newspapers glorified the brilliance of ball décor, for there is nothing unostentatious about supping in a gleaming statue gallery. However, as his letter makes clear, the luxury of dance itself was also a focal point. After describing the remainder of the arrangements, he noted that he had “erected a scaffold outside the Dancing room to enable the Ladies maids to have a peep at their mistresses”. Due to overcrowding, the scaffolding soon collapsed, but its inclusion points towards the stark realities of class. For servants, elite balls were an untouchable luxury, something heard of or commented upon, or participated in only through service. Lord Grantham’s arrangements allowed them to peer at the dancing ladies and gentlemen, but active engagement in dancing was off-limits. A similar voyeuristic structure was in place at Wentworth Woodhouse, where the gallery encircling the saloon was continually refilled with people, including “the more respectable of the tenantry” (Morning Chronicle 3 October 1834). Such structures turned both dance and luxury into a spectacle to be behold from a distance by the lower classes.

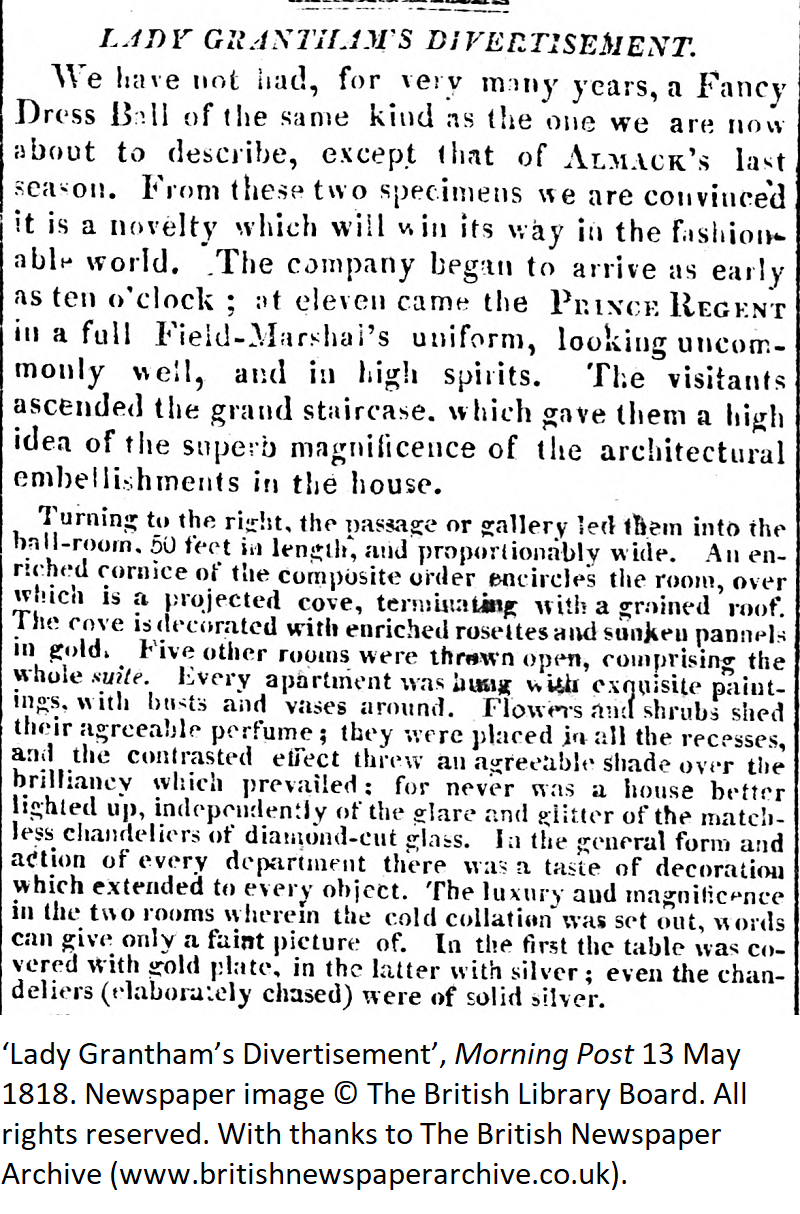

Five months prior to the ball at Newby Hall, Lady Grantham hosted a fancy dress ball at the home of her husband’s aunt in St James’s Square in London. The Morning Post’s description of the event reads as an essay in opulence: the decorative qualities of the interiors were extolled (“never was a house better lighted up, independently of the glare and glitter of the matchless chandeliers of diamond-cut glass”); the gold and silver plate used for supper were breathlessly hinted at (“The luxury and magnificence in the two rooms wherein the cold collation was set out, words can give only a faint picture of”); and the costumes and their wearers were blindingly praised (“The Ladies’ dresses, formed of gold or silver lame [sic], enriched with diamonds and pearls, and plumes of ostrich feathers towering in the full plenitude of beauty, exhibited the most dazzling richness, elegance, and taste”). This deliberate and ostentatious depiction of luxury was reinforced by a comparison with Almack’s Assembly Rooms and the presence of dignitaries such as the Prince Regent. Such “inflationary tendencies” were common in newspaper coverage, which at times poured forth the language of excess, but in this case at least there was some truth behind the descriptions (Russell 2007, 31).

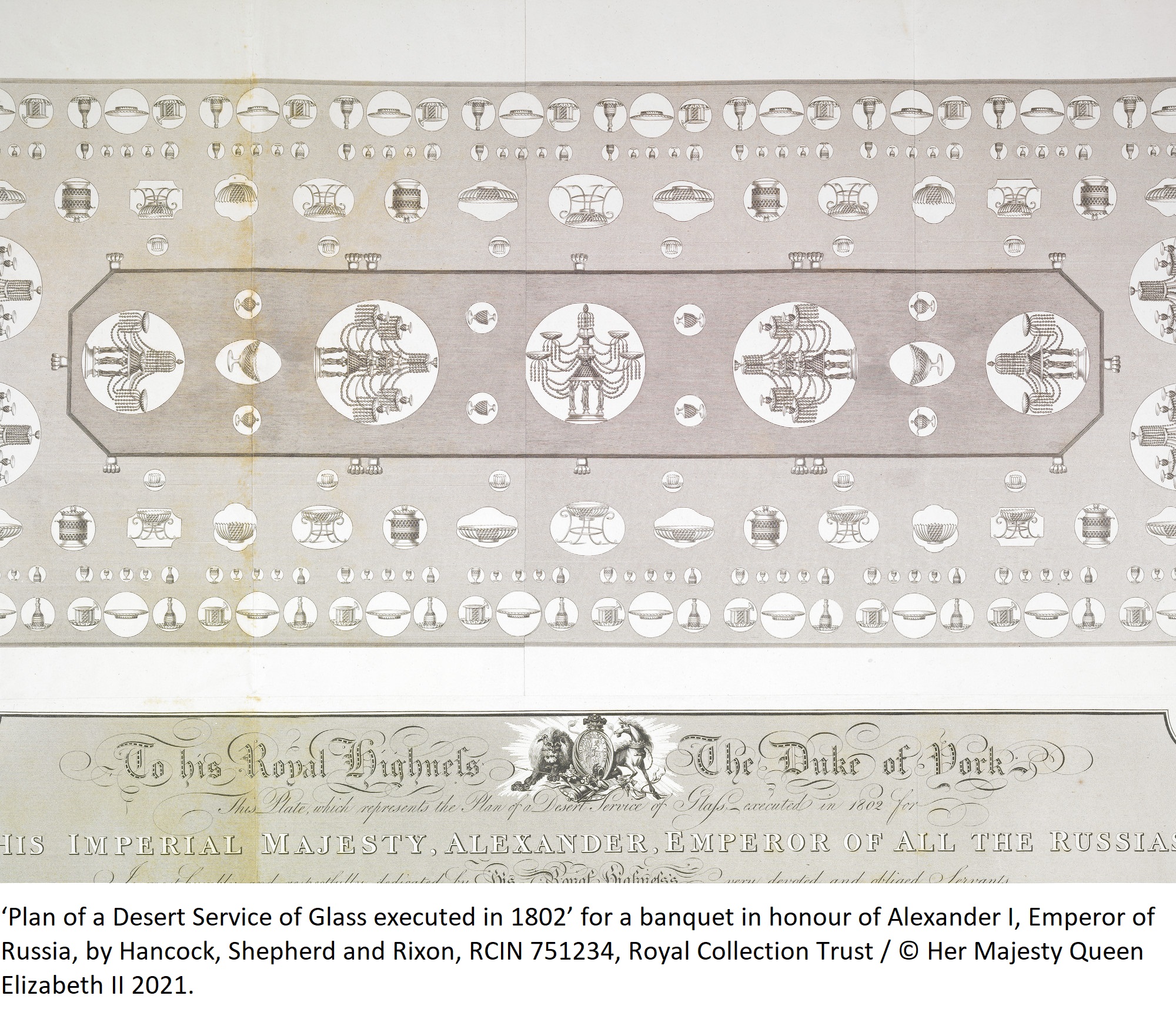

Invoices and receipts for the ball provide solid evidence of the event’s opulence. The majority of the documents refer to the purchase of food and drink, and the hire of lighting, tables and chairs. Two of the most extensive and expensive listings concern lamps and confectionery. Both tableware and confectionery were luxury purchases, the latter sometimes comprising elaborate decorative features and sculptures, allowing hosts to exhibit taste and wealth whilst at the same time catering for pleasure and comfort (Stobart and Rothery 2016; Avery and Calaresu 2019). The glass manufacturers Hancock, Shepherd and Rixon loaned a wealth of lamps, lights and drinking glasses, including Grecian lamps, Gothic feet lamps, gold coloured pedestals and more than a hundred each of lemonade glasses and goblets. In the confectionery line were jams, jellies, fruits, wafers, macaroons and various kinds of cakes. Other food-related purchases comprised wines, bread, meats (including calves’ feet), tea, sugar, anchovies and almonds (Bedfordshire Archives L31/376/1-23). Given the weight of emphasis, even if the survival of documents is incomplete, it is easy to see why newspapers lavished attention on portraying choice delicacies and arresting lighting.

The objects that impart this sense of luxury are visual, aromatic, and to a certain extent, tactile. Any sense of aural opulence is rather muted, if indeed it appears at all; the Morning Post’s account of the ball makes no mention of the music, a curious if not unfamiliar omission given the nature of the entertainment. Amongst the receipts and invoices, though, is a payment of £12 12s to James Paine for providing ten musicians for the ball. Paine was the leader of one of the most prominent dance bands in London, regularly playing at Almack’s and other fashionable balls. The employment of his band, like the various payments for other goods, represents a luxury in its own right: the luxury to choose the most fashionable sound. A good band was a vital ingredient in determining the quality of the dance experience and to match the glittering event, the band also needed to sparkle.

The objects that impart this sense of luxury are visual, aromatic, and to a certain extent, tactile. Any sense of aural opulence is rather muted, if indeed it appears at all; the Morning Post’s account of the ball makes no mention of the music, a curious if not unfamiliar omission given the nature of the entertainment. Amongst the receipts and invoices, though, is a payment of £12 12s to James Paine for providing ten musicians for the ball. Paine was the leader of one of the most prominent dance bands in London, regularly playing at Almack’s and other fashionable balls. The employment of his band, like the various payments for other goods, represents a luxury in its own right: the luxury to choose the most fashionable sound. A good band was a vital ingredient in determining the quality of the dance experience and to match the glittering event, the band also needed to sparkle.

Despite the differences in location and the huge disparity in numbers between the two balls – Lady Grantham’s ball reportedly accommodated near a thousand guests – the approaches to luxury were similar. Both showcased luxury goods, whether these were permanent fixtures of the house or on temporary loan, in an effort to place the focus of the ball on the building and its contents. Certainly the considerable investment in lighting was common to both, which accentuated interior and exterior architectural features, and enabled any gilded surface to gleam. And although no musicians from London were employed for the ball at Newby Hall, Lord Grantham hired a local equivalent: the band that played for the York Winter Assemblies under the direction of William Hardman, which two months after the ball was described as “one of the first out of London” (York Herald 19 December 1818). Dance, although a key part of these entertainments, essentially offered an opportunity to display consumer taste and purchasing power to a sometimes astonishing degree.

Further Reading:

Avery, Victoria and Melissa Calaresu, eds. 2019. Feast & Fast: The Art of Food in Europe 1500-1800. London: Philip Wilson Publishers.

Cleminson, Antony. 1991. “Christmas at Kingston Lacy: Frances Bankes’s Ball of 1791.” Apollo: The International Magazine of the Arts (December): 405-409.

Russell, Gillian. 2007. Women, Sociability and Theatre in Georgian London. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stobart, Jon, and Mark Rothery. 2016. Consumption and the Country House. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Newspaper References:

Newby Hall: Leeds Intelligencer 19 October 1818; York Herald 24 October 1818.

Wentworth Woodhouse: Morning Post 4 October 1834.

Grantham London ball: Morning Post 23 April 1818.