![James Caldwall and Charles Grignion after Robert Adam, ‘Inside view of the Supper-room & part of the Ball-room in a Pavilion erected for a Fête Champêtre in the Garden of the Earl of Derby at the Oaks in Surry [sic], the 9th of June, 1774’, 1780 © The Trustees of the British Museum. James Caldwall and Charles Grignion after Robert Adam, ‘Inside view of the Supper-room & part of the Ball-room in a Pavilion erected for a Fête Champêtre in the Garden of the Earl of Derby at the Oaks in Surry [sic], the 9th of June, 1774’, 1780 © The Trustees of the British Museum.](https://sound-heritage.ac.uk/sites/sound-heritage.soton.ac.uk/files/styles/fix_width_1100/public/james_caldwall_charles_grignion_-_inside_view_of_the_supper_room_the_oaks_1780_british_museum_-_main_image.wc_.jpg?itok=PoBN-tHF)

Dance and Luxury: Staging Spectacle

On 9 June 1774, a stunning fête champêtre was staged at The Oaks in Surrey ahead of the impending marriage between Edward Smith Stanley, future 12th Earl of Derby and Lady Elizabeth (Betty) Hamilton, daughter of the 6th Duke of Hamilton and the subsequent Duchess of Argyll. Carefully curated by General John Burgoyne, uncle to Lord Stanley by marriage, it was a highly complex piece of political and social theatre, drawing on history, nationalism, allegory and disguise (O’Quinn 2011). It was also considerably expensive, reportedly costing thousands of pounds (Nelson 1999), a lavish display of luxury and extravagance which prompted Mary Granville to exclaim that “nothing at least in modern days has been exhibited so perfectly magnificent” (Hall Llanover 1862, 1).

Through a series of alternating masques and balls, the fête champêtre also flexed some serious artistic muscle: the music was directed and composed by François-Hippolyte Barthélemon, one of London’s leading violinists; the dancers were overseen by Monsieur Lépy, ballet master at the King’s Theatre; and vocal solos were performed by Joseph Vernon and Maria Barthélemon, who maintained active theatrical careers. In what was perhaps a nod to Lady Elizabeth’s Scottish heritage, it also featured the work of two of Scotland’s finest eighteenth-century exports: the composer, Thomas Alexander Erskine, 6th Earl of Kelly, and the renowned architect, Robert Adam. Indeed, Adam’s temporary pavilion housing much of the entertainment was perhaps one of the most extraordinary aspects of the occasion. With a ballroom at its core, surrounded by columns and supper rooms, it shaped the performance of the final masque and the balls that flanked it (Doderer-Winkler 2013; Nelson 1999).

Through a series of alternating masques and balls, the fête champêtre also flexed some serious artistic muscle: the music was directed and composed by François-Hippolyte Barthélemon, one of London’s leading violinists; the dancers were overseen by Monsieur Lépy, ballet master at the King’s Theatre; and vocal solos were performed by Joseph Vernon and Maria Barthélemon, who maintained active theatrical careers. In what was perhaps a nod to Lady Elizabeth’s Scottish heritage, it also featured the work of two of Scotland’s finest eighteenth-century exports: the composer, Thomas Alexander Erskine, 6th Earl of Kelly, and the renowned architect, Robert Adam. Indeed, Adam’s temporary pavilion housing much of the entertainment was perhaps one of the most extraordinary aspects of the occasion. With a ballroom at its core, surrounded by columns and supper rooms, it shaped the performance of the final masque and the balls that flanked it (Doderer-Winkler 2013; Nelson 1999).

Throughout the spectacle Burgoyne indulged in the art of surprise and disguise, a fitting theatrical ploy given that the guests themselves were in masquerade dress (Lewis 1967). Musicians were deliberately concealed from their audience: as guests arrived on the lawn they were greeted by the sound of hidden French horns, while at the orangerie for the first masque, they were surprised by the sounds of Barthélemon’s band emanating from the shrubbery. In a less than subtle manoeuvre, Burgoyne interrupted the performance of minuets and cotillions between the masques with an explosion which signalled the sudden appearance of supper, startling his guests before enticing them with “the most costly dainties, all hot and tempting” (General Evening Post 14-16 June 1774; O’Quinn 2011).

![James Caldwall after Robert Adam, ‘Inside view of the Ball-room in a Pavilion erected for a Fête Champêtre in the Garden of the Earl of Derby at the Oaks in Surry [sic], the 9th of June, 1774’, 1780 © The Trustees of the British Museum. James Caldwall after Robert Adam, ‘Inside view of the Ball-room in a Pavilion erected for a Fête Champêtre in the Garden of the Earl of Derby at the Oaks in Surry [sic], the 9th of June, 1774’, 1780 © The Trustees of the British Museum.](/sites/sound-heritage.soton.ac.uk/files/adam_fete_champetre_ballroom_-_british_museum.wc_.jpg)

This spirit of concealment extended beyond the life of the entertainment. The final ball of the fête champêtre had begun with Lord Stanley and Lady Hamilton dancing minuets by Kelly, an apt finale given the minuet was both a theatrical dance and a court dance par excellence which presented a stylised exhibition of refined courtship. A few months later, Kelly’s minuets were published by William Napier as The Favourite Minuets Perform’d at the Fetè Champêtre. Although newspaper accounts of the event claimed they were “composed on the occasion” by Kelly, they are actually pre-existing compositions, some of which were given new titles to reflect the principal personages in the event (Johnson 2005). The masking effect of such deliberate retitling mimicked the theatrical nature of the spectacle, honouring Burgoyne’s efforts at disguise, and was presumably also an effective marketing technique.

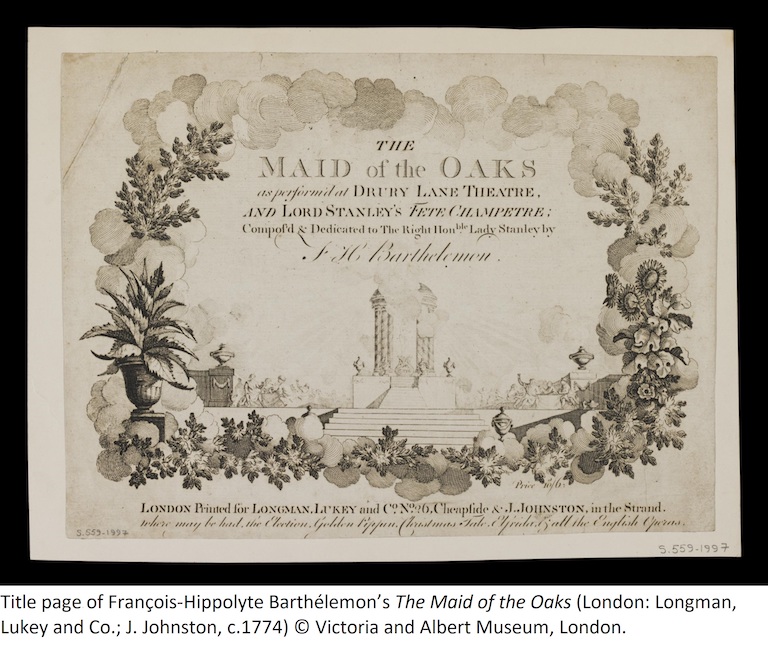

Another musical legacy of the fête champêtre was The Maid of the Oaks, a “dramatic entertainment” penned by Burgoyne with musical numbers largely by Barthélemon (Burden 1995; Nelson 1999). Originally conceived in two acts and written for the fête, it was subsequently enlarged seemingly at David Garrick’s instigation and premiered at Drury Lane in November 1774 (Maid of the Oaks 1774; Fiske 1973). It incorporated a fête champêtre in celebration of the wedding of the female protagonist (the Maid of the Oaks) and contains various references to the real event; the final act opens with a minuet danced inside a representation of Adam’s pavilion and concludes with a grand dance. The production mirrored (or at least suggested) elements of excess from the original gala: press accounts reported scenery by Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg cost the “prodigious Sum” of £1500; Garrick’s prologue equated the show with the goldsmith James Cox’s luxury ornamented jewellery and automata (Russell 2007b); and the King Street theatre in Bristol advertised the use of nearly a thousand lamps in its staging in 1775. Whilst Garrick could get away with aristocratic luxury on the English opera stage, the dancers could not – although one newspaper described The Maid of the Oaks as “a Dish of the choicest Kind, drest by the best Stage Cook in the Kingdom…suited to the Eye, the Ear, and the Understanding”, it also noted that pit audiences “have no Taste for Dances made up of fine Attitudes and stately studied Measures”, relegating minuets to the Italian opera house instead (St. James’s Chronicle 5-8 November 1774).

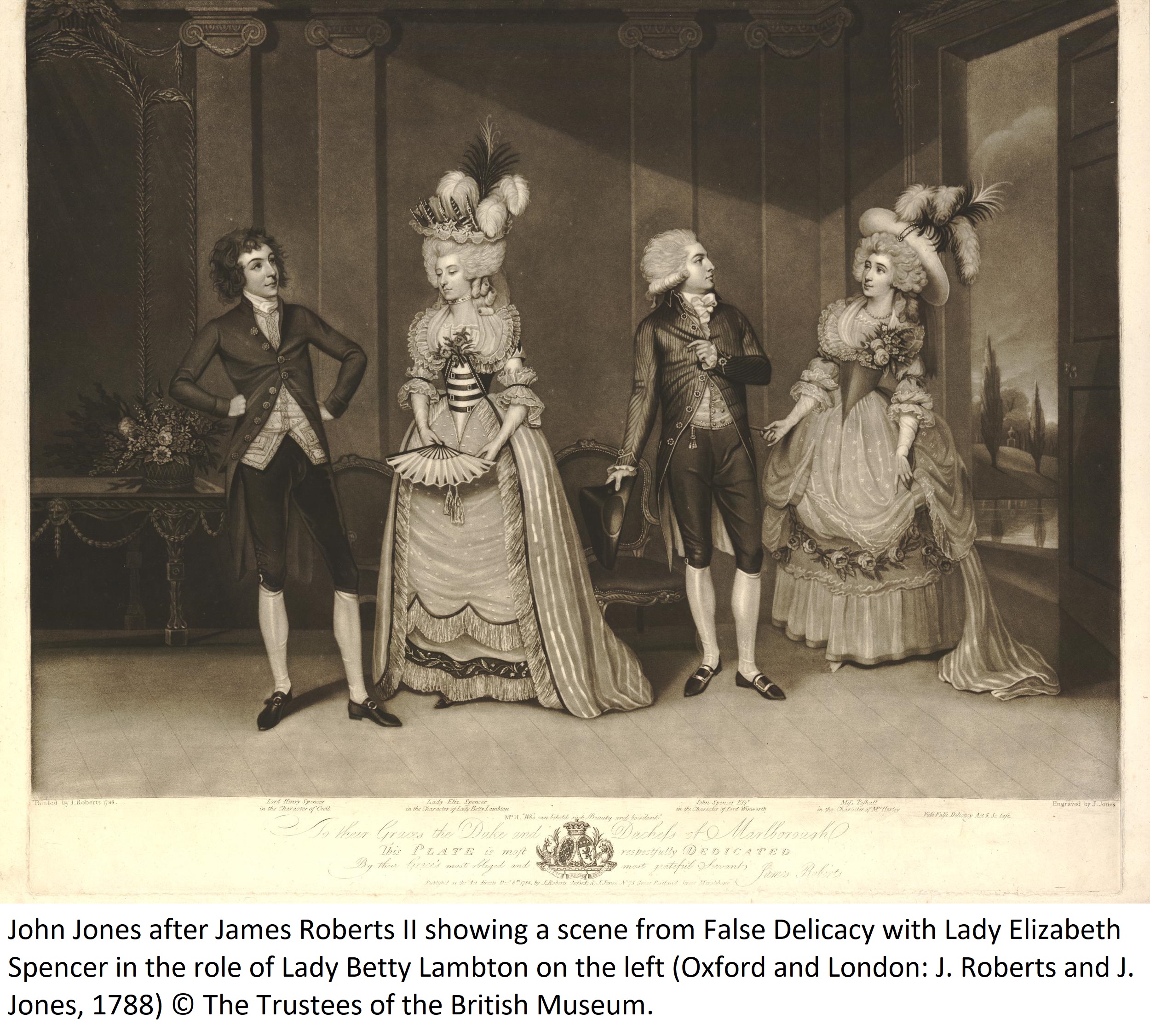

Fourteen years later, The Maid of the Oaks was staged in a private theatrical performance at Blenheim Palace, home of the Duke of Marlborough, in a move which fittingly closed a social circle. At the top end of the scale, private theatricals were lavish affairs comprising purpose-built theatres, specially designed tickets and playbills, and the employment of theatre professionals (Russell 2007a); the Blenheim theatre was created out of the existing greenhouse and featured scenery by Michael Angelo Rooker, scene-painter at the Haymarket theatre. Performances of The Maid of the Oaks were accompanied by the Duke’s band and concluded with a ballet which counted the Marlborough daughters, Ladies Caroline and Elizabeth Spencer, amongst the dancers (Rosenfeld 1978). Included in the ballet was Lady Elizabeth Spencer’s Minuet, composed by Philip Hayes and dedicated to the Duchess of Marlborough, for which an autograph manuscript survives dating from early in the production’s run. Both the Duke and Duchess were present at Lord Stanley’s fête champêtre and thus would have borne first-hand witness to the original production of Burgoyne’s work and the performance of minuets, including those by Kelly; Burgoyne returned the favour by attending The Maid of the Oaks at Blenheim when it was revived in 1789 (Rosenfeld 1978). The performance was thus a kind of recreation of their own experience, but on their own turf, and on their own terms.

Fourteen years later, The Maid of the Oaks was staged in a private theatrical performance at Blenheim Palace, home of the Duke of Marlborough, in a move which fittingly closed a social circle. At the top end of the scale, private theatricals were lavish affairs comprising purpose-built theatres, specially designed tickets and playbills, and the employment of theatre professionals (Russell 2007a); the Blenheim theatre was created out of the existing greenhouse and featured scenery by Michael Angelo Rooker, scene-painter at the Haymarket theatre. Performances of The Maid of the Oaks were accompanied by the Duke’s band and concluded with a ballet which counted the Marlborough daughters, Ladies Caroline and Elizabeth Spencer, amongst the dancers (Rosenfeld 1978). Included in the ballet was Lady Elizabeth Spencer’s Minuet, composed by Philip Hayes and dedicated to the Duchess of Marlborough, for which an autograph manuscript survives dating from early in the production’s run. Both the Duke and Duchess were present at Lord Stanley’s fête champêtre and thus would have borne first-hand witness to the original production of Burgoyne’s work and the performance of minuets, including those by Kelly; Burgoyne returned the favour by attending The Maid of the Oaks at Blenheim when it was revived in 1789 (Rosenfeld 1978). The performance was thus a kind of recreation of their own experience, but on their own turf, and on their own terms.