Networks - 4th Earl of Abingdon: Dedicating to Family and Friends

Willoughby Bertie, 4th Earl of Abingdon (1740-1799) liked to reflect his familial and social networks in his choice of dance titles. He published two substantial collections: Twelve Country Dances and Three Capricios…with three Minuets (1787) and Nine Country Dances and Three Minuets for the Year 1789. The country dances in the former collection are on the whole given rather generic names, such as Fops Alley, April Showers and All in the wrong. One exception to this is La Bachelli, which may refer to the artist and singer, Alice Bacchelli. She appeared in concert in 1775 at the Hanover Square Rooms, one of London’s most exclusive music venues. Bacchelli’s inclusion in Abingdon’s publication has its counterpart in the third capriccio, titled The Siddons, an obvious reference to the acclaimed actress, Sarah Siddons (McCulloch 2000).

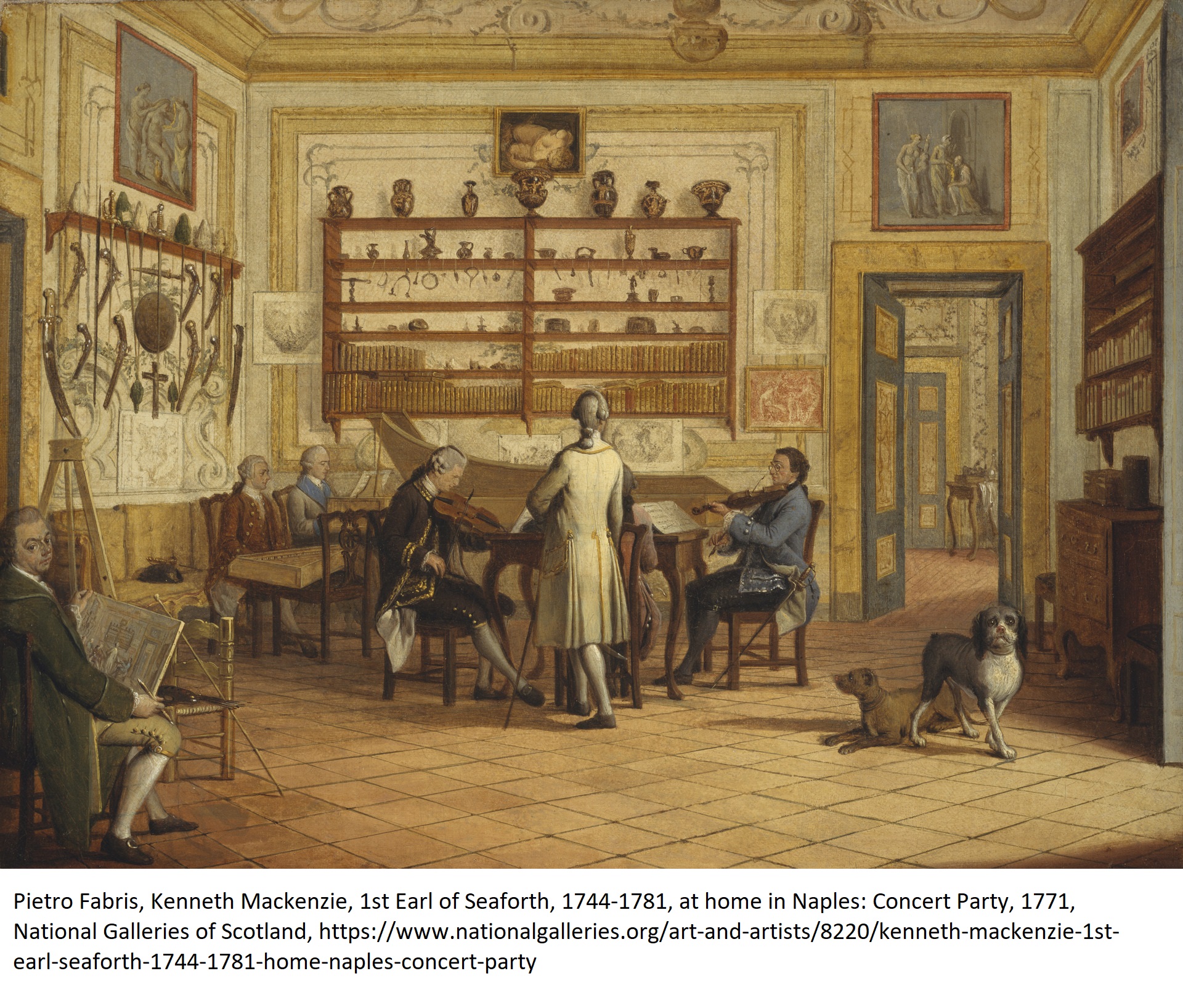

The remainder of Abingdon’s dances, including nearly the entirety of the Nine Country Dances collection, are named after recognisable women and reveal rich personal connections across his extended family and acquaintance. Susanna Maria Skinner was Abingdon’s niece by marriage; her mother, Susanna Warren, was a sister of Abingdon’s wife, Charlotte, and had married Colonel William Skinner in 1767. The Warren family owned considerable property in America, Ireland and England thanks to the legacy of Admiral Sir Peter Warren, Susanna Maria’s grandfather. In 1787, the year Miss Skinners Minuet was published in Twelve Country Dances, Abingdon reached an agreement with Susanna Maria and his brother-in-law, Charles FitzRoy, 1st Baron Southampton, regarding the division amongst them of Warren properties in New York state (Gwyn 1974). Susanna Maria’s marriage to Henry Gage, 3rd Viscount Gage in 1789 makes a persuasive argument that two other works in Abingdon’s oeuvre were also named after her: Le Gage d’Amour in Nine Country Dances, produced the year she married, and Twenty-One Vocal Pieces (1797), dedicated to Lady Viscountess Gage. The FitzRoy connection was further touched upon in Lady Caroline Mackenzies Frolick – her grandmother was an aunt to Charles FitzRoy, while her father, Kenneth Mackenzie, 1st Earl of Seaforth, shared Abingdon’s interest in music (Dietz 1992; Schnapp 2013).

The remainder of Abingdon’s dances, including nearly the entirety of the Nine Country Dances collection, are named after recognisable women and reveal rich personal connections across his extended family and acquaintance. Susanna Maria Skinner was Abingdon’s niece by marriage; her mother, Susanna Warren, was a sister of Abingdon’s wife, Charlotte, and had married Colonel William Skinner in 1767. The Warren family owned considerable property in America, Ireland and England thanks to the legacy of Admiral Sir Peter Warren, Susanna Maria’s grandfather. In 1787, the year Miss Skinners Minuet was published in Twelve Country Dances, Abingdon reached an agreement with Susanna Maria and his brother-in-law, Charles FitzRoy, 1st Baron Southampton, regarding the division amongst them of Warren properties in New York state (Gwyn 1974). Susanna Maria’s marriage to Henry Gage, 3rd Viscount Gage in 1789 makes a persuasive argument that two other works in Abingdon’s oeuvre were also named after her: Le Gage d’Amour in Nine Country Dances, produced the year she married, and Twenty-One Vocal Pieces (1797), dedicated to Lady Viscountess Gage. The FitzRoy connection was further touched upon in Lady Caroline Mackenzies Frolick – her grandmother was an aunt to Charles FitzRoy, while her father, Kenneth Mackenzie, 1st Earl of Seaforth, shared Abingdon’s interest in music (Dietz 1992; Schnapp 2013).

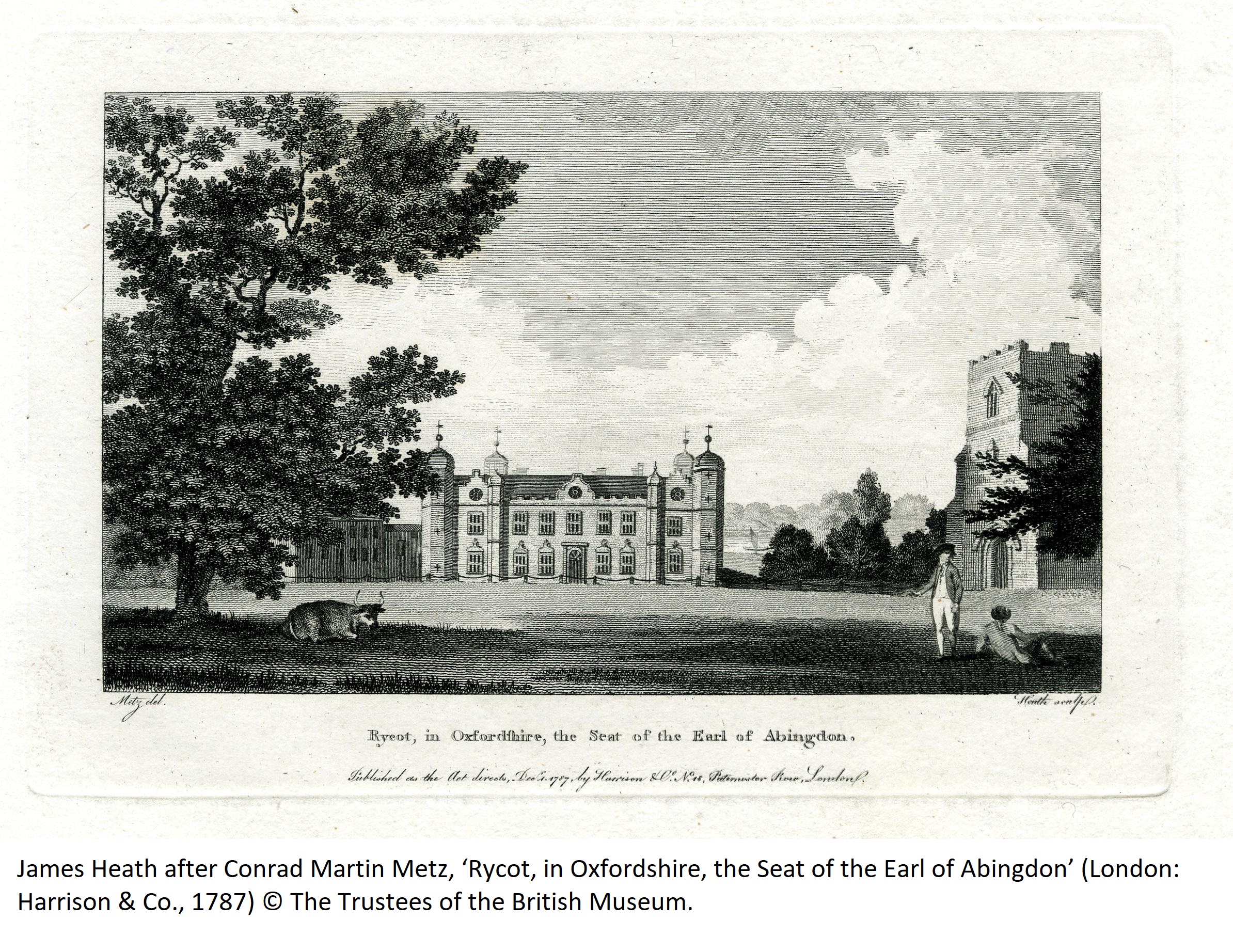

Other dances in Abingdon’s publications reflect his social and cultural engagements. After the death of Johann Christian Bach in 1782, he took over the management of the Bach-Abel concert series at the Hanover Square Rooms the following year (McVeigh 1989). The Rooms themselves were a family affair: the site was purchased by one of Abingdon’s brothers-in-law (Philip Wenman, 7th Viscount Wenman), who then passed it on to Giovanni Gallini, another brother-in-law (Forsyth 1985; Jones et al. 2001). Audience members for the concert series included Lady Jane Aston, her sister Lady Bridget Tollemache, and Caroline Spencer, 4th Duchess of Marlborough, each of whom have minuets named after them. The Duchess and Lady Bridget also subscribed to boxes at the King’s Theatre which were almost directly opposite the box that Abingdon shared. Lady Jane was the wife of Abingdon’s friend, Sir Willoughby Aston, 6th Baronet, whom Abingdon visited with Joseph Haydn in 1794. The Astons, along with Lady Bridget, the Wenmans and a host of other names, subscribed to Abingdon’s Six Songs & a Duet in 1788 (McCulloch 2000). Abingdon’s use of names also points towards his neighbours in Oxfordshire. Arabella and Catharine Cope, playfully immortalised in Miss Arrabella Cope’s Enjouement and Miss Catherine Copes Agrèmèns, were the daughters of Sir Charles Cope, whose family seat of Bruern Abbey was across the other side of Oxford from Abingdon’s own country residence of Rycote.

Other dances in Abingdon’s publications reflect his social and cultural engagements. After the death of Johann Christian Bach in 1782, he took over the management of the Bach-Abel concert series at the Hanover Square Rooms the following year (McVeigh 1989). The Rooms themselves were a family affair: the site was purchased by one of Abingdon’s brothers-in-law (Philip Wenman, 7th Viscount Wenman), who then passed it on to Giovanni Gallini, another brother-in-law (Forsyth 1985; Jones et al. 2001). Audience members for the concert series included Lady Jane Aston, her sister Lady Bridget Tollemache, and Caroline Spencer, 4th Duchess of Marlborough, each of whom have minuets named after them. The Duchess and Lady Bridget also subscribed to boxes at the King’s Theatre which were almost directly opposite the box that Abingdon shared. Lady Jane was the wife of Abingdon’s friend, Sir Willoughby Aston, 6th Baronet, whom Abingdon visited with Joseph Haydn in 1794. The Astons, along with Lady Bridget, the Wenmans and a host of other names, subscribed to Abingdon’s Six Songs & a Duet in 1788 (McCulloch 2000). Abingdon’s use of names also points towards his neighbours in Oxfordshire. Arabella and Catharine Cope, playfully immortalised in Miss Arrabella Cope’s Enjouement and Miss Catherine Copes Agrèmèns, were the daughters of Sir Charles Cope, whose family seat of Bruern Abbey was across the other side of Oxford from Abingdon’s own country residence of Rycote.

The Marlboroughs were also Oxfordshire neighbours and crucially provide a tangible context for understanding Abingdon’s dance compositions. In 1782 they hosted a ball at Blenheim Palace, which was attended by Abingdon and his wife. The ball commenced with country dances before moving on to minuets, where Lady Elizabeth Spencer and her older sister, Lady Caroline Spencer, performed the Minuet de la Cour. A manuscript music book belonging to Lady Caroline, dated the same year as the ball, contains minuets by Abingdon named after both sisters, in addition to compositions by Lady Elizabeth, including country dances and a minuet. It’s not known when Abingdon composed the minuets and they are slighter than those published in his Twelve Country Dances, but they are on a par with other printed minuets. It’s conceivable that the dances were either included in and/or inspired by such a ball, suggesting that Abingdon’s naming practices in general may have had a more concrete basis in dance beyond the mere assignation of names to compositions.

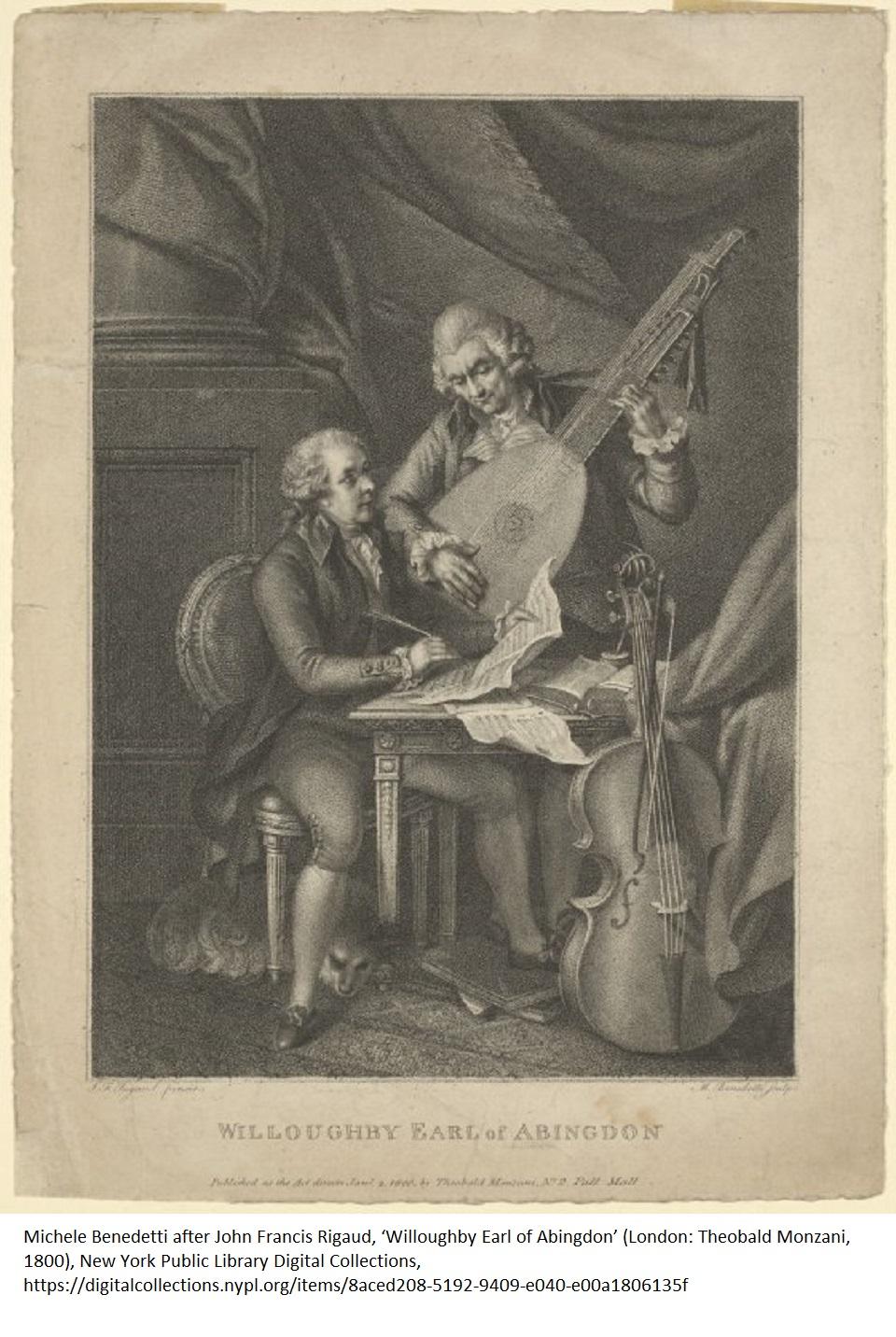

The name that appears most amongst Abingdon’s dances is that of Lady Charlotte Bertie, captured in Lady Charlotte Berties Minuet, Lady Charlotte Berties Capricio and Lady Charlotte Berties Delight. This likely refers to Abingdon’s eldest daughter, who was the dedicatee for Haydn’s second set of Six Original Canzonettas (1795), rather than his wife (McCulloch 2000). Lady Charlotte was clearly unwell around the time her minuet was published in Twelve Country Dances, but her recovery included music - the family travelled to Weymouth for restorative sea bathing and were “accompanied in their excursion by a small but select party of musical amateurs” (General Advertiser 10 September 1787). Touchingly, her memory was preserved in the dedication to the first edition of William Shield’s An Introduction to Harmony, published after her death in January 1799. She was also commemorated by the painter John Francis Rigaud in a watercolour commissioned by her father. Rigaud had previously captured Abingdon in the craft of composition and had also depicted Lady Charlotte with a harp in an earlier family portrait. He drew on this again in the watercolour, showing her "sitting in a garden, surrounded with bushes and flowers, by the side of a stream of water, playing upon a harp, as expressed in a song, composed for her Ladyship, at Oxford, in which she is called Amanda, and set to music by his Lordship" (Rigaud and Pressly 1984, 108).

The name that appears most amongst Abingdon’s dances is that of Lady Charlotte Bertie, captured in Lady Charlotte Berties Minuet, Lady Charlotte Berties Capricio and Lady Charlotte Berties Delight. This likely refers to Abingdon’s eldest daughter, who was the dedicatee for Haydn’s second set of Six Original Canzonettas (1795), rather than his wife (McCulloch 2000). Lady Charlotte was clearly unwell around the time her minuet was published in Twelve Country Dances, but her recovery included music - the family travelled to Weymouth for restorative sea bathing and were “accompanied in their excursion by a small but select party of musical amateurs” (General Advertiser 10 September 1787). Touchingly, her memory was preserved in the dedication to the first edition of William Shield’s An Introduction to Harmony, published after her death in January 1799. She was also commemorated by the painter John Francis Rigaud in a watercolour commissioned by her father. Rigaud had previously captured Abingdon in the craft of composition and had also depicted Lady Charlotte with a harp in an earlier family portrait. He drew on this again in the watercolour, showing her "sitting in a garden, surrounded with bushes and flowers, by the side of a stream of water, playing upon a harp, as expressed in a song, composed for her Ladyship, at Oxford, in which she is called Amanda, and set to music by his Lordship" (Rigaud and Pressly 1984, 108).

With a few exceptions, the majority of the women named in Abingdon’s dances were of a similar age to Lady Charlotte and it is tempting to speculate that they may have been her friends as well as her relatives. In this light, Abingdon captured a whole social circle through dance, with his Nine Country Dances collection in particular standing as a broad testament to his fondness for his daughter.