Dance Instrumentation in Britain

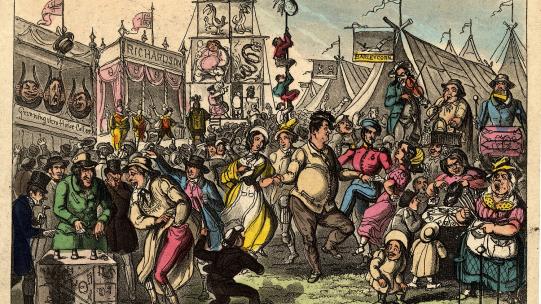

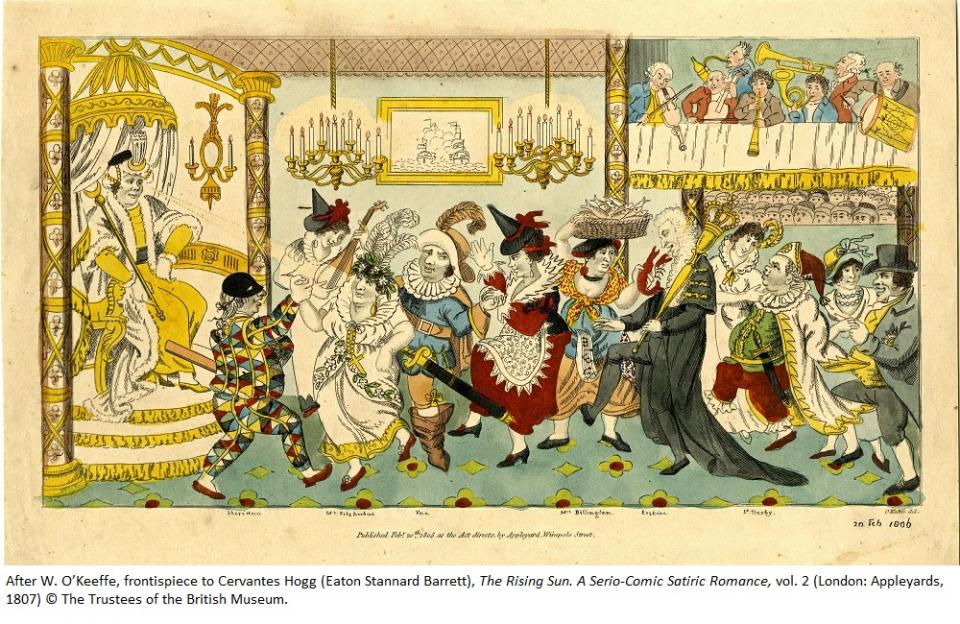

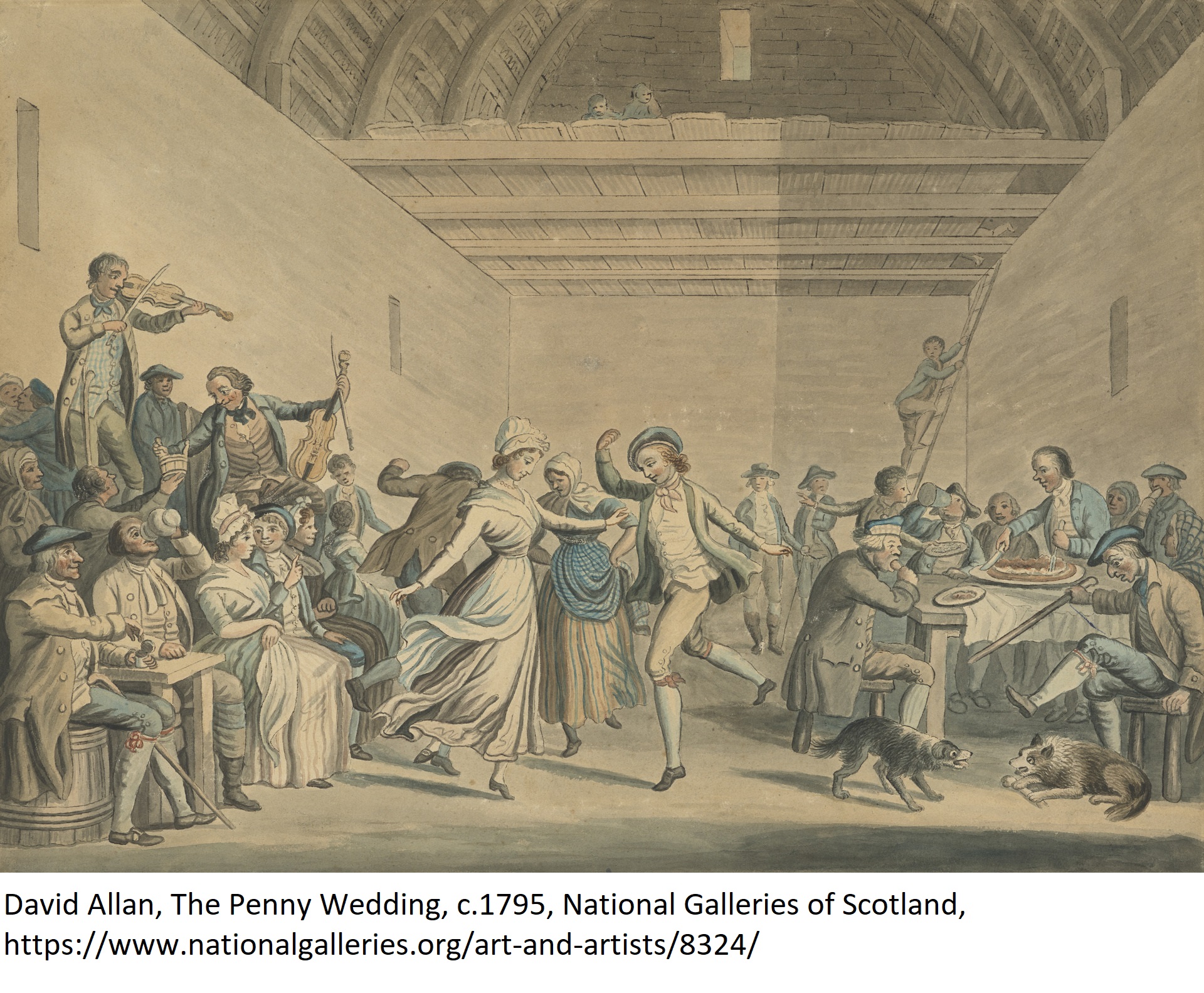

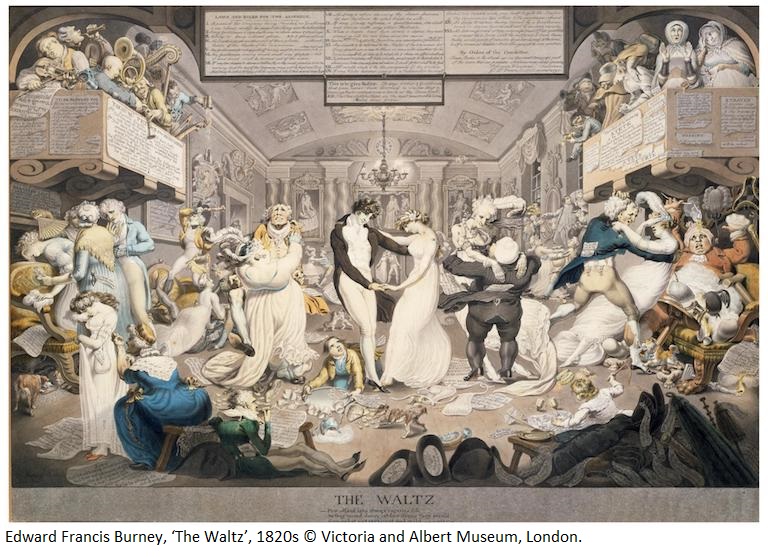

Despite the popularity of dance and its prominence as a social pastime, we currently know very little about the sound of the bands that played for balls in the Georgian era. Newspaper accounts of such events, which provide a wealth of general information, are surprisingly silent about the musicians; named performers often don’t appear until around the 1820s, although band leaders are more regularly mentioned. Surviving dance music scores for piano or harp with optional additional instruments, or collections of dance tunes published for violin, oboe or flute, catered for the domestic market and are not reliable indicators of the make-up of dance bands. Counterbalancing this lacuna are other sources such as artistic representations of dance bands; receipts, letters and diary entries; and some extant instrumental scores for dance music. While iconography is not necessarily entirely reliable, combining these sources brings us a lot closer to understanding what dance bands sounded like.

It’s clear that music ensembles playing for balls were diverse. They could comprise as little as one or two fiddlers or a lone harpist: in 1778 Fritz Robinson wrote of “an odd kind of ball, I say odd, because there was no musick but a harp” in London, while music for assemblies in Bodmin were provided by “a blind fiddler and a little scraper, his son” (Bedfordshire Archives L30/14/333/103; Jenkin 1988, 151). Even by the mid nineteenth century, the novelist Thomas Hardy played the fiddle for dances as a teenager, where “at the end of a three-quarter-hour’s unbroken footing to his notes by twelve tireless couples” he was stopped for fear of his health (Hardy 1928, 29). At the other end of the spectrum royal and high-profile elite balls employed bands that comprised thirty or more performers. John Thomas Louis Weippert’s “full band of seventy performers” was engaged for a Royal Academy of Music ball in 1842; if the numbers are to be believed, they evidently backfired as “The orchestra was good in itself, but too obstreperous with the too great proportion of wind instruments”.

It’s clear that music ensembles playing for balls were diverse. They could comprise as little as one or two fiddlers or a lone harpist: in 1778 Fritz Robinson wrote of “an odd kind of ball, I say odd, because there was no musick but a harp” in London, while music for assemblies in Bodmin were provided by “a blind fiddler and a little scraper, his son” (Bedfordshire Archives L30/14/333/103; Jenkin 1988, 151). Even by the mid nineteenth century, the novelist Thomas Hardy played the fiddle for dances as a teenager, where “at the end of a three-quarter-hour’s unbroken footing to his notes by twelve tireless couples” he was stopped for fear of his health (Hardy 1928, 29). At the other end of the spectrum royal and high-profile elite balls employed bands that comprised thirty or more performers. John Thomas Louis Weippert’s “full band of seventy performers” was engaged for a Royal Academy of Music ball in 1842; if the numbers are to be believed, they evidently backfired as “The orchestra was good in itself, but too obstreperous with the too great proportion of wind instruments”.

Sometimes the combinations appeared to be a little improvised and unreliable. On Christmas Eve in 1777, Elizabeth Harris wrote to her daughter Gertrude (Fritz Robinson’s future wife) about “A lady of Scotch quality in the Close, who has la[tely] given a ball and had no other music than Mrs Legg[e’s] footman and the first man in the Regimental, an[other who cou]ld not or would not play country dances and Mrs [Legge’s] man could not play above three or four” (Burrows and Dunhill 2002, 966). It’s important to note that some musicians were multi-instrumentalists, enabling a greater range of colour whilst keeping costs lower. In 1772 James Woodforde wrote of a “private Hop or Dance” which involved “2. Clarionettes, one French. Horn, 2 Violins & a Base [sic] Viol – but they were only 3 Hands, viz, M.r Hooper & two other of Hoopers Company” (Winstanley 1988, 5).

Dance bands were not necessarily fixed entities and it’s evident that dance musicians played with other musical organisations. In the Morning Post on 3 April 1827, Weippert advertised “that he provides and conducts QUADRILLE BANDS of every description” and that “his Bands consists [sic] of the first Performers in the Kingdom, selected from the Orchestras of the King’s Theatre, principal Concerts, &c.”. Despite the influence of prominent French musicians such as Philippe Musard and Hubert Collinet on  London’s ball scene, many of the players they engaged were also employed by the King’s Theatre. It’s currently unclear how much cross-over there was between different dance bands; certainly, cross-fertilisation was also taking place at a provincial level. A ball in Devon in 1837 included performers from the Bath Philharmonic Society and a Marine band (some of whom had previously played with one of the Weippert outfits) as well as musicians from Plymouth and Totnes. Just a couple of weeks earlier Weippert’s band combined with horn, trombone and clarinet players from the Plymouth Marine Band for a ball at Bicton.

London’s ball scene, many of the players they engaged were also employed by the King’s Theatre. It’s currently unclear how much cross-over there was between different dance bands; certainly, cross-fertilisation was also taking place at a provincial level. A ball in Devon in 1837 included performers from the Bath Philharmonic Society and a Marine band (some of whom had previously played with one of the Weippert outfits) as well as musicians from Plymouth and Totnes. Just a couple of weeks earlier Weippert’s band combined with horn, trombone and clarinet players from the Plymouth Marine Band for a ball at Bicton.

This interchangeability of musicians between different forms of music-making was also evident in Bath, where it is possible to partially reconstruct the bands that played for balls in the New (Upper) Assembly Rooms. Archival documents list the names of musicians who were engaged to perform at the Rooms in the early 1770s; some additionally played for concerts as well as balls, and a number were also employed by the Orchard Street Theatre, thus contributing significantly to Bath’s musical life. One of the band members was James Brooks, a prominent Bath violinist and composer who was engaged to play for concerts and balls at the Rooms at around the age of eleven to fourteen; another was Taverner Wilkie/Wilkey, a victualler at the Butchers’ Market. If the listing of names is complete, the band for balls comprised between seven and ten performers, although some were proficient on several instruments: Alexander Herschel, younger brother of William, played the violin, cello, oboe and clarinet; James Cantelo was a flautist and oboist; and both father and son under the name of William Rogers were trained to play horn, trumpet and strings (James 1987).

fourteen; another was Taverner Wilkie/Wilkey, a victualler at the Butchers’ Market. If the listing of names is complete, the band for balls comprised between seven and ten performers, although some were proficient on several instruments: Alexander Herschel, younger brother of William, played the violin, cello, oboe and clarinet; James Cantelo was a flautist and oboist; and both father and son under the name of William Rogers were trained to play horn, trumpet and strings (James 1987).

A number of different professions acted as go-betweens for those who wished to procure dance band musicians. Music and instrument sellers, teachers, dancing masters and even inn owners all advertised their ability to provide music for quadrille parties and other events. It’s not always clear what the “music” comprised although some musicians were engaged as pianists; one such performer was the organist Joseph Binns Hart, who went on to lead a quadrille band and published a significant quantity of dance music (Cooper 2014). It’s not known whether Hart’s quadrille publications reflected what he himself played or whether they were versions specifically produced for the domestic market. Occasionally more precise instrument combinations surface: an advertisement in the Morning Post on 14 January 1840 from the music publisher Charles Ollivier announced that he could “secure the attendance of the best Performers on the Pianoforte, Harp, Violin, Flageolet, Cornopean, and all instruments suited to Quadrille Parties”.

The instrumental composition of dance music ensembles could be colourful and sometimes unexpected. The most enduring instruments across this period were the violin and tabor & pipe, the latter being a small drum and single-handed three-holed pipe played by a sole performer. As late as the 1820s, the tabor & pipe featured in the dance band engaged for tenants’ balls at Eaton Hall, which also included violins, cellos, double bass, bassoon and horn. The harp appeared prominently in iconography in the late 1810s but solo harpists, particularly Welsh harpists, were employed from at least the 1770s (Winstanley 1986). In 1832, Mr Horabin’s band was made up of two violins, cello, double bass, harp, two horns, flageolet and clarinet. The flageolet bears some resemblance to the recorder, although nineteenth-century instruments also included keys and double or triple flageolets were manufactured which enabled performers to play more than one note at once. Hubert Collinet was one of the finest exponents of the instrument and his popularity may have stimulated the inclusion of the flageolet in local dance bands; the ensemble for the Devon ball included dance music “arranged for two Clarionets, two Cornets a Piston, and Flageolet Obligato, with full orchestra accompaniments”.

The instrumental composition of dance music ensembles could be colourful and sometimes unexpected. The most enduring instruments across this period were the violin and tabor & pipe, the latter being a small drum and single-handed three-holed pipe played by a sole performer. As late as the 1820s, the tabor & pipe featured in the dance band engaged for tenants’ balls at Eaton Hall, which also included violins, cellos, double bass, bassoon and horn. The harp appeared prominently in iconography in the late 1810s but solo harpists, particularly Welsh harpists, were employed from at least the 1770s (Winstanley 1986). In 1832, Mr Horabin’s band was made up of two violins, cello, double bass, harp, two horns, flageolet and clarinet. The flageolet bears some resemblance to the recorder, although nineteenth-century instruments also included keys and double or triple flageolets were manufactured which enabled performers to play more than one note at once. Hubert Collinet was one of the finest exponents of the instrument and his popularity may have stimulated the inclusion of the flageolet in local dance bands; the ensemble for the Devon ball included dance music “arranged for two Clarionets, two Cornets a Piston, and Flageolet Obligato, with full orchestra accompaniments”.

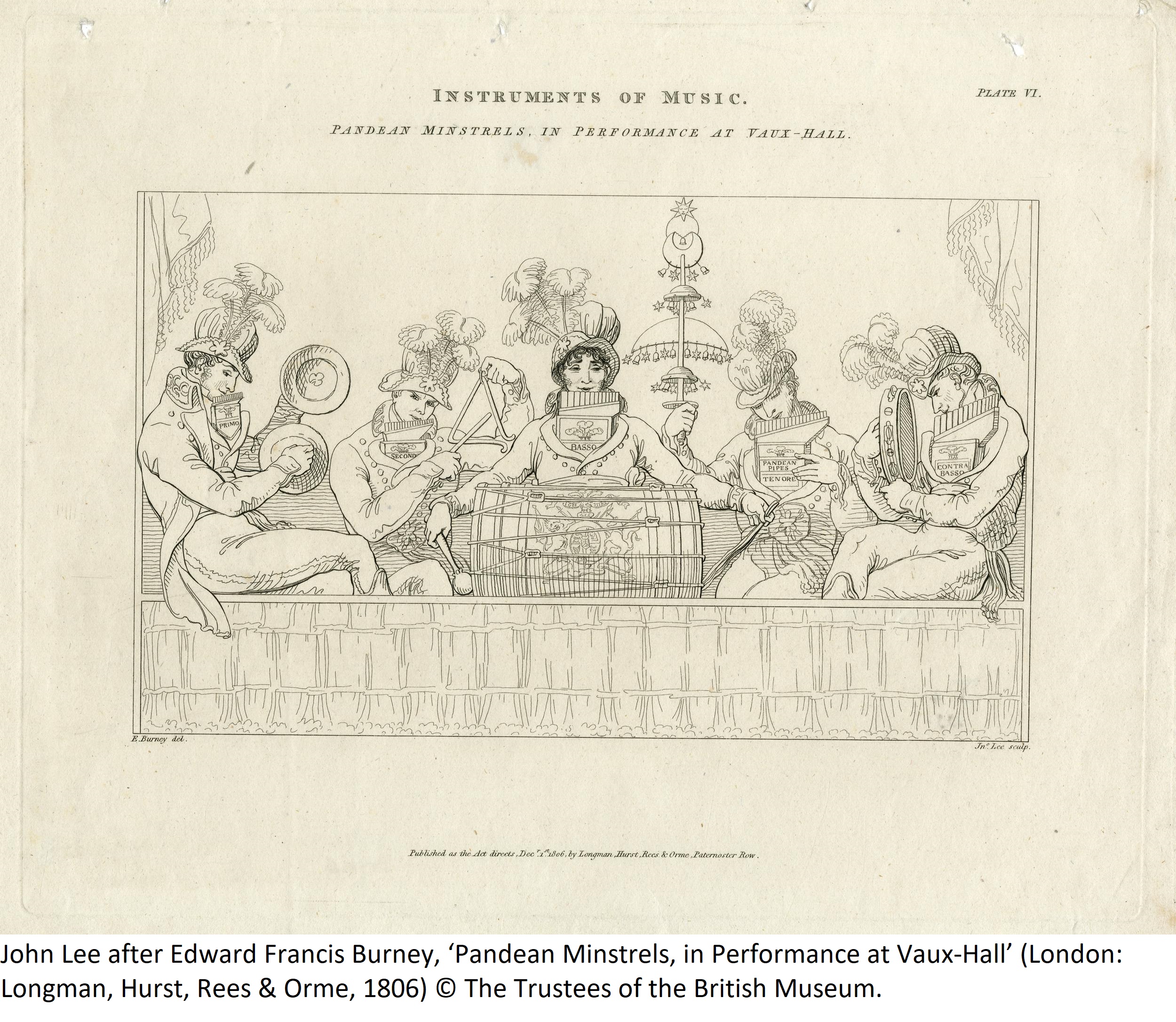

One of the more intriguing instrumental choices was the Pandean (pan) pipes. In the early nineteenth century they were played by street musicians, sometimes in combination with a drum, for fairs, processions and puppet shows. They were also part of miscellaneous theatrical performances and featured in novelty acts like Signor Rivolta’s, who included the Pandean pipes amongst an array of instruments he claimed to play simultaneously. Rivolta appears to have led a band called the Pandean Minstrels, comprising five sizes of pipes and several percussion instruments, with the later addition of two guitars. Most, if not all, of the musicians likely played on more than one instrument at once. The band was engaged to play at Vauxhall pleasure gardens, fetes, masquerades and private gatherings (Coke and Borg 2011). In 1809 dancing master Thomas Wilson hosted a “Grand Rural Ball” where the Pandean Minstrels played on the lawn prior to the ball. He featured such pipe players in dance ensembles illustrated in A Companion to the Ballroom and A Description of the Correct Method of Waltzing, both published in 1816. It’s unclear whether Wilson’s representations reflect actual practice or whether they were simply inspired by the popularity of the Pandean Minstrels. They mostly provided incidental music while other bands catered for dancing at balls, but there is some evidence that Pandean pipes were used to accompany dance: in 1816 celebrations for the Prince Regent’s birthday in Barnstaple included “a rustic dance, accompanied by pandean pipes, clarionets, and tamborines”.

amongst an array of instruments he claimed to play simultaneously. Rivolta appears to have led a band called the Pandean Minstrels, comprising five sizes of pipes and several percussion instruments, with the later addition of two guitars. Most, if not all, of the musicians likely played on more than one instrument at once. The band was engaged to play at Vauxhall pleasure gardens, fetes, masquerades and private gatherings (Coke and Borg 2011). In 1809 dancing master Thomas Wilson hosted a “Grand Rural Ball” where the Pandean Minstrels played on the lawn prior to the ball. He featured such pipe players in dance ensembles illustrated in A Companion to the Ballroom and A Description of the Correct Method of Waltzing, both published in 1816. It’s unclear whether Wilson’s representations reflect actual practice or whether they were simply inspired by the popularity of the Pandean Minstrels. They mostly provided incidental music while other bands catered for dancing at balls, but there is some evidence that Pandean pipes were used to accompany dance: in 1816 celebrations for the Prince Regent’s birthday in Barnstaple included “a rustic dance, accompanied by pandean pipes, clarionets, and tamborines”.

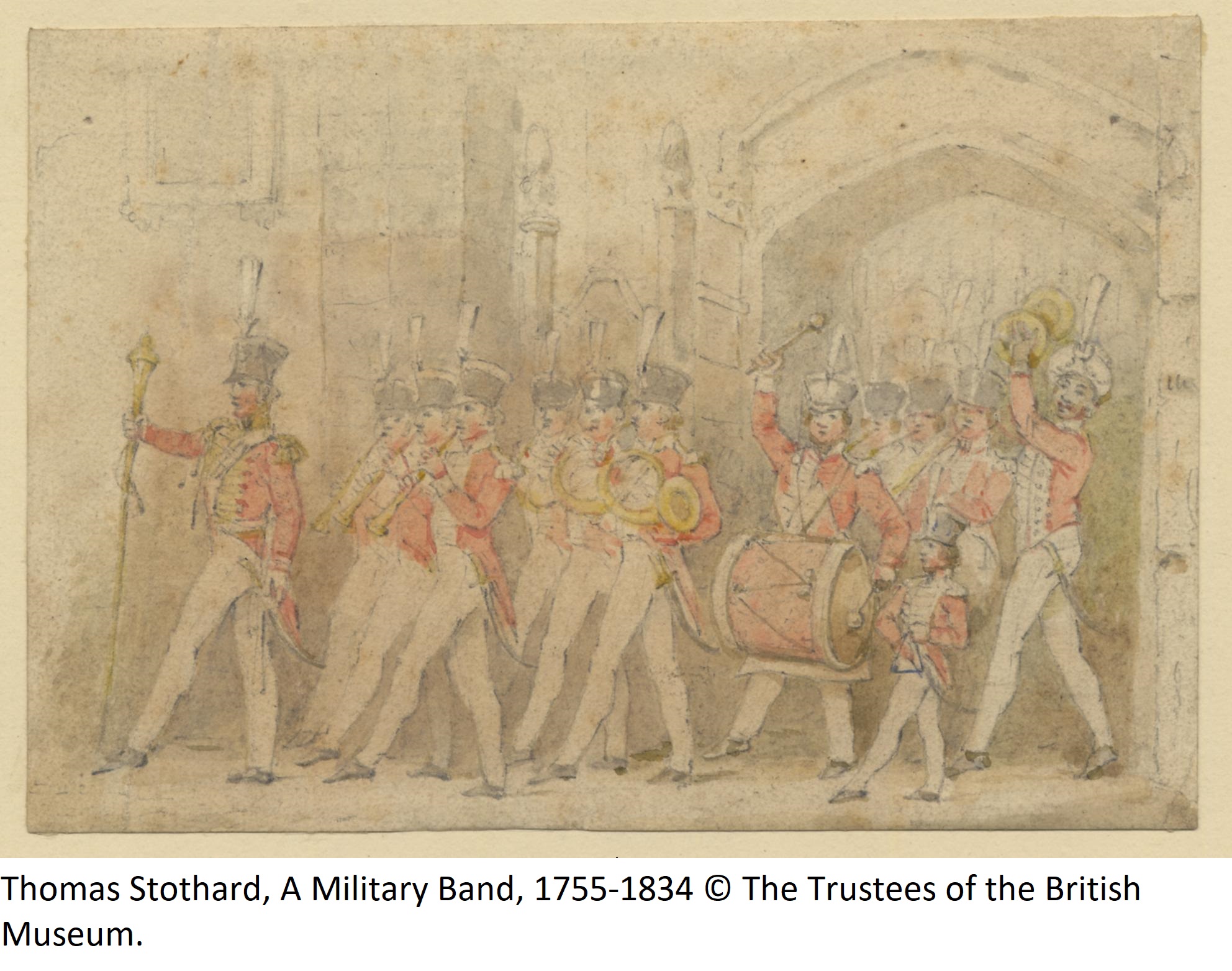

The percussion instruments employed by the Pandean Minstrels, such as cymbals, tambourines and triangles, were already being used in regimental bands due to the popularity of ‘Turkish’ music in the late eighteenth century. Militia and volunteer corps bands were not standardised entities, but at this time they were most likely to comprise clarinets, horns and bassoons, sometimes with the inclusion of flutes or fifes, and a bass drum; subsequent additions included trumpets, bugle horns and serpents.  In the 1770s militia bands largely numbered around six to eight players, although there were some exceptions, and this doubled around twenty years later (Lomas 1989,1990). In the early years of the nineteenth century the “return of music books and instruments” for the Shropshire Regiment of Militia band comprised 8 flutes, 7 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, a serpent, bugle, bass horn, trombone and assorted percussion, suggesting twenty-eight musicians in total (Herbert and Barlow 2013, 111). There is also some evidence that regimental band musicians doubled on string instruments. Regimental bands were often engaged to perform incidental music at balls when a professional dance band was hired, but they also played for dance themselves. Sometimes this was an improvised arrangement – Elizabeth Harris reported on 25 August 1776 that “Lord Pembroke sent his regimental band here yesterday [:] they are Germans and play well. They so animated the Dean of Sarum, Mrs Earle, Mrs Sympson and your father that they gott [up] and danc’d” (Burrows and Dunhill 2002, 905).

In the 1770s militia bands largely numbered around six to eight players, although there were some exceptions, and this doubled around twenty years later (Lomas 1989,1990). In the early years of the nineteenth century the “return of music books and instruments” for the Shropshire Regiment of Militia band comprised 8 flutes, 7 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, a serpent, bugle, bass horn, trombone and assorted percussion, suggesting twenty-eight musicians in total (Herbert and Barlow 2013, 111). There is also some evidence that regimental band musicians doubled on string instruments. Regimental bands were often engaged to perform incidental music at balls when a professional dance band was hired, but they also played for dance themselves. Sometimes this was an improvised arrangement – Elizabeth Harris reported on 25 August 1776 that “Lord Pembroke sent his regimental band here yesterday [:] they are Germans and play well. They so animated the Dean of Sarum, Mrs Earle, Mrs Sympson and your father that they gott [up] and danc’d” (Burrows and Dunhill 2002, 905).

The Harris family was one of many who staged private theatricals and the ensembles used to accompany such productions offer an additional insight into dance instrumentation. It’s clear that the bands could be idiosyncratic and dependent upon circumstances. Some were domestically oriented in their various combinations of organ, piano, tambourine, cello and violin as described by the painter Thomas Lawrence at Bentley Priory in 1803. Others employed leading professional performers and the Duke of Richmond combined members of the Sussex Militia band with his own private musicians to form a group of sixteen players for theatricals at Richmond House in the late 1780s (Rosenfeld 1978). Perhaps the clearest example comes from performances of The Maid of the Oaks at Blenheim Palace, home to the Duke of Marlborough, in 1788. The production finished with a ballet which included Lady Elizabeth Spencer’s Minuet, named after one of the Marlborough daughters, composed by Philip Hayes. The published score, held at the British Library, is for 2 horns, 2 flutes/clarinets/oboes, 2 violins, viola and bassi, with a built-in harpsichord part. An autograph manuscript of the minuet, dating from early in the production’s run, is nearly identically scored for 2 horns, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 violins, viola and basso continuo. The Morning Chronicle on 21 January 1788 noted that “Several capital performers were engaged in addition to his Grace’s own band” for the production. Given the presence of the autograph score, it’s likely that it represents the composition of the band for the performance.

Hayes’s scoring is similar to other published minuets, suggesting that such instrumentation may have been common amongst (augmented) private bands and possibly adapted for regimental ensembles. Certainly, there was a commercial impulse behind such publications which can’t be fully explained by the inclusion of a keyboard part. The combination of horns with winds and strings is fairly commonplace, as shown in Matthew Peter King’s The Princess of Wales Minuett, The Earl of Barrymore’s Minuet and François-Hippolyte Barthélemon’s The Princess of Wales’s Minuet. Manuscript minuets from the Royal Music Collection at the British Library and the Hanover Royal Music Archive at the Beinecke Library, along with published minuets by William Parsons for royal birthday balls in the late eighteenth century, show a similar kind of scoring. Some of the British Library minuets appear to be written for keyboard but are clearly labelled to include instruments such as clarinets and horns, suggesting (despite the inclusion of a figured bass) that the score itself is shorthand for string instrumentation. A manuscript minuet from the Theodore M. Finney Collection scored for 2 horns, 2 oboes, 2 violins and bass includes a request for “three first violins, three Sec.d violins, 2 Horns[,] 2 Oboes, & 2 Violoncello’s of this Minuet” to be copied, presumably as parts, illustrating how the instrumentation could be expanded and was therefore mutable. David Johnson outlined a progression in published Scottish minuets, ranging from horns, winds and strings with separate violin parts, through to unison fiddles and cello or even a lone fiddler, with the simpler ensembles associated with increased circulation (Johnson 2005).

and was therefore mutable. David Johnson outlined a progression in published Scottish minuets, ranging from horns, winds and strings with separate violin parts, through to unison fiddles and cello or even a lone fiddler, with the simpler ensembles associated with increased circulation (Johnson 2005).

Dance bands were housed in elevated galleries or “orchestras,” the latter being a raised platform or recess which Samuel Johnson simply defined as “The place where the musicians are set at a publick show” (Girouard 1990; Johnson 1768). A number of public venues contained music galleries in their entertainment rooms, including the Ship Inn in Brighton, Mansion House in Doncaster, the Town Hall in Liverpool and the Guildhall in Bath (Parliamentary Gazetteer 1851; Wright 1818). The assembly rooms in York originally contained no gallery but the Great Assembly Room (‘Egyptian Hall’) seemed to acquire “a very neat music gallery” by the nineteenth century, if not before (Hargrove 1818, 471; Girouard 1990). The Royal Artillery Mess at Woolwich barracks gained a music gallery around 1816, while purpose-built ballrooms at Chatsworth and Goodwood (the former of which could double as a theatre prior to its actual conversion in the 1890s) also featured galleries (Adam 1857; Guillery 2012). The ubiquity of galleries is reflected in iconography, from small structures containing as few as two musicians through to more ornate balconies holding between six and thirteen players. While depictions of platforms also included these kinds of numbers, they also accommodated substantially larger numbers of performers in prominent public venues. In the domestic setting, this sometimes occasioned extreme architectural alterations – Edward Smith Stanley, future 12th Earl of Derby, held a ball at Derby House in London in 1773, for which “The Ball Room had one of the Side Walls taken down & a large Orchestra & 2 Niches carried into the Garden” (Doderer-Winkler 2013, 60).

In addition to these music galleries, a number of assembly rooms, other public buildings and some private houses contained organs which would have been used for dance music. The rotundas at both Ranelagh and Vauxhall had organs as part of their orchestra stands, with Vauxhall having an additional external building specifically housing an organ early in the eighteenth century (Coke and Borg 2011). Other pleasure gardens such as Bagnigge Wells and Lord Cobham’s Head had organs installed in their main or long rooms (Wroth 1979). As assembly rooms catered for concerts as well as balls (and in Buxton’s case also religious services), an organ was a regular fixture, employed in assembly rooms in York, Bath, Salisbury and Chichester, and other venues such as the  Castle Inn in Brighton and the York House Hotel and Tavern in Clifton (Burrows and Dunhill 2002; Hargrove 1818; Improved Bath Guide 1809?; Wright 1818). In 1775 Elizabeth Harris wrote from Salisbury that “Thursday was the common assembly that you know ends at eleven, and away goes the fiddlers. Then Benson Earle mounts the scaffolding and plays cotillons on the organ[,] to which music all the masters and misses dance for near an hour”; she subsequently quipped, “Yesterday we spent at the Earles[:] that was tolerably quiet, and so will this day be, unless they dance cotillons in the church this afternoon, to their favorite instrument the organ” (Burrows and Dunhill 2002, 862). The diaries of Sophia Baker, daughter of William Baker MP of Bayfordbury, often mention dancing to the organ within a domestic context, but it’s unclear if she was referring to a barrel or chamber organ (West Sussex Record Office Add Mss 7462-7514). Many stately homes contained organs, in secular spaces such as entrance halls or music rooms where they would also have been used to accompany dance.

Castle Inn in Brighton and the York House Hotel and Tavern in Clifton (Burrows and Dunhill 2002; Hargrove 1818; Improved Bath Guide 1809?; Wright 1818). In 1775 Elizabeth Harris wrote from Salisbury that “Thursday was the common assembly that you know ends at eleven, and away goes the fiddlers. Then Benson Earle mounts the scaffolding and plays cotillons on the organ[,] to which music all the masters and misses dance for near an hour”; she subsequently quipped, “Yesterday we spent at the Earles[:] that was tolerably quiet, and so will this day be, unless they dance cotillons in the church this afternoon, to their favorite instrument the organ” (Burrows and Dunhill 2002, 862). The diaries of Sophia Baker, daughter of William Baker MP of Bayfordbury, often mention dancing to the organ within a domestic context, but it’s unclear if she was referring to a barrel or chamber organ (West Sussex Record Office Add Mss 7462-7514). Many stately homes contained organs, in secular spaces such as entrance halls or music rooms where they would also have been used to accompany dance.

For those who wished to try and imitate the fuller sonority of a dance band at home there were a variety of mechanical musical instruments to choose from. Barrel organs, which were popular from the mid-eighteenth century in England, supplied both sacred and secular music, including dances (Langwill and Ord-Hume 2001). An advertisement in the Morning Advertiser on 6 May 1808, specifically targeted at trade to the East Indies, announced the sale of “a Capital Flageolet Barrel ORGAN, with Tabor, Drum, Cymbols [sic], &c…with 5 barrels, containing a selection of the most popular and modern tunes, of songs, marches, airs, dances, overture, &c.”. Dancing master Edward Payne advertised his invention of a “Quadrille Organ”, which performed “with the greatest precision a complete set of Quadrilles, without shifting the Barrel, having the effect of a Band” (Payne 1818, [136]). The Manchester Courier described the flageolet piano on 21 July 1832 as a contraption attached to or located under a piano, “producing the effect of two instruments at the same moment” and acting as “an excellent substitute for the flute to accompany the voice or harp…and great variety in playing quadrilles on the piano-forte”. Other instruments included the Royal Orchestrina and the Choremusicon, the latter professedly “combining the tones of the Pianoforte, Bassoon, Violoncello, Clarionet [sic], Flageolet…producing the effect of a well-organised band” but only requiring a single performer.

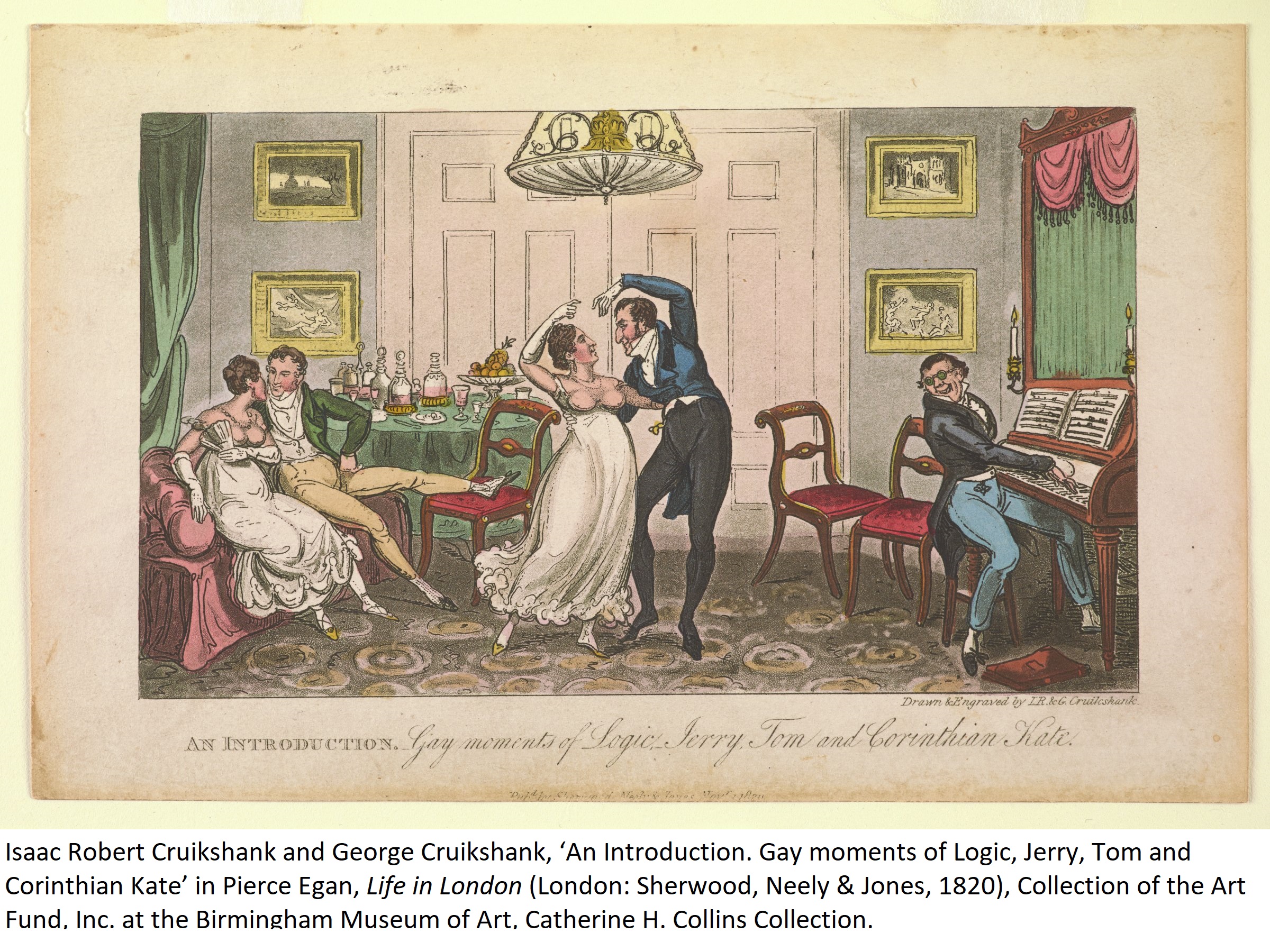

While much dance music was arranged for the piano, there is so far little evidence that the instrument itself was actually used within professional dance bands. The piano is absent from both descriptions of the constitution of dance bands and their depiction in iconography. An exception to this seems to have occurred when Lewis Moss led the band for a ball on the Isle of Wight in 1828, where “his accompaniment on the Flageolet Piano, an instrument new to the musical world, was much admired”. There are many examples, however, of the use of the piano to accompany dance at home, either on its own or in combination with other instruments. In 1778, the composer John Marsh described a dance which was accompanied by piano, flute and fiddle, with performers taking turns to play on the piano (Robins 1998). The diaries of Sophia Baker contain numerous references to dancing to the piano in the 1790s and early 1800s. Whilst the portrayal of dancing to the piano in Pierce Egan’s Life in London suggests lascivious entertainment, and a rare undated watercolour of black dance possibly by Robert F. Watson shows energetic dancing to music provided by a horn and piano (King-Dorset 2008), John Marshall’s inclusion of accompanying dance at the piano in The Infant’s Library positioned it as a pedagogical skill, both musically and socially. For extra effect, pianos like that sold by Corri, Dussek & Co. incorporated the sound of a tambourine and triangle, useful “where many times a social dance would terminate the evening, but that it has been thought of too late to procure the Tambourine and Fidler [sic] from the next town” (Rowland 2012, 93).

While much dance music was arranged for the piano, there is so far little evidence that the instrument itself was actually used within professional dance bands. The piano is absent from both descriptions of the constitution of dance bands and their depiction in iconography. An exception to this seems to have occurred when Lewis Moss led the band for a ball on the Isle of Wight in 1828, where “his accompaniment on the Flageolet Piano, an instrument new to the musical world, was much admired”. There are many examples, however, of the use of the piano to accompany dance at home, either on its own or in combination with other instruments. In 1778, the composer John Marsh described a dance which was accompanied by piano, flute and fiddle, with performers taking turns to play on the piano (Robins 1998). The diaries of Sophia Baker contain numerous references to dancing to the piano in the 1790s and early 1800s. Whilst the portrayal of dancing to the piano in Pierce Egan’s Life in London suggests lascivious entertainment, and a rare undated watercolour of black dance possibly by Robert F. Watson shows energetic dancing to music provided by a horn and piano (King-Dorset 2008), John Marshall’s inclusion of accompanying dance at the piano in The Infant’s Library positioned it as a pedagogical skill, both musically and socially. For extra effect, pianos like that sold by Corri, Dussek & Co. incorporated the sound of a tambourine and triangle, useful “where many times a social dance would terminate the evening, but that it has been thought of too late to procure the Tambourine and Fidler [sic] from the next town” (Rowland 2012, 93).

As an addition to existing forces or perhaps in the absence of instrumentalists, the voice could be used to provide dance music. Singing had long since occurred in masquerades either as part of the general entertainment or to portray particular masquerade characters (Robins 1998). But during the 1830s vocal dance music was on the rise; now, singing was combined with instrumental performance to create a novel effect in quadrilles, galops and waltzes. A “celebrated vocal galloppe” was performed by Weippert’s band during a state ball for Princess Victoria’s seventeenth birthday. The Cheltenham Looker-On described how “about half the Band [was] singing a chorus at intervals during the dance”. A month later, when presumably the same piece was performed at a Royal Academy of Music ball, this portrayal was expanded upon: “while the band plays those who perform on the stringed instruments sing the harmony of the common chord and that of the dominant, merely pronouncing “La, la, la,” &c., marking the time with their voices”. By 1838, An Essay on the Art of Dancing advised young ladies to practise their dancing whilst singing harmonised melodies. Ten years later the Swedish soprano Jenny Lind sang quadrilles for her fellow performers while staying at a hotel in Dublin between opera engagements (Levey and O’Rorke 1880). A few earlier sources suggest that this practice may have emerged as early as the 1800s. A manuscript copy of The New Grand O.P. Dance, presumably a reference to the Covent Garden price riots in 1809, has “O.P.” specifically marked under the notes, suggesting they were vocalised. And the co-existence of some dance tunes as songs means, of course, that they could have been sung or whistled in the absence of instrumentalists (Gilchrist 1940).