Dance Spaces

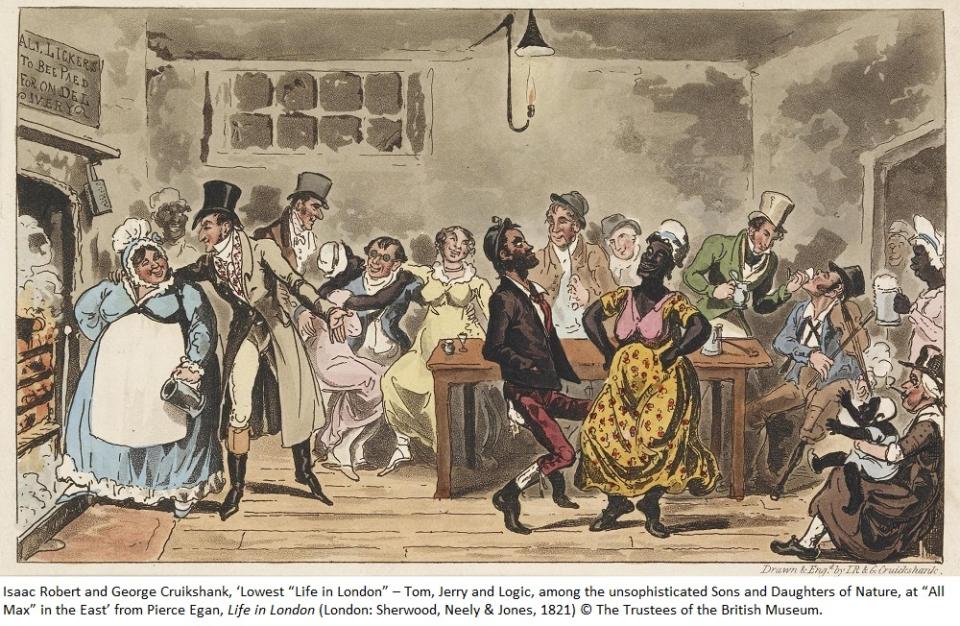

In the eighteenth and earlier nineteenth centuries, occasions to dance were staged in a wide variety of places. They were rarely purpose-built for dancing but were often sites for general social and cultural life. Below are the most common spaces in which people participated in social dance.

Assembly Rooms

Assembly Rooms

Assembly rooms were a flourishing feature of eighteenth-century social life. They were a staple in spa towns but by the end of the century many provincial locations also had their own assembly rooms. They were multi-purpose venues, catering for dancing, concerts, cards, billiards, reading, tea-drinking, private gatherings, exhibitions and lectures (Girouard 1990). While this multi-functionality could be concurrent, sometimes it was increasingly evident later in the life of a given rooms’ history: Almack’s Assembly Rooms, one of London’s most exclusive dance venues, also hosted high profile concerts during its heyday, but the diversity and richness of activities appeared to increase as it went deeper into decline (Beresford Chancellor 1922; McVeigh 1993). Assembly rooms could be financed by various methods including private speculation or through a group of subscribers, but they were an expensive undertaking; outside of spas, provincial towns could struggle to support such ventures in the absence of sufficient visitor numbers and therefore the need for such rooms was less pressing, particularly if civic or community facilities were already available (Girouard 1990; Stobart 2000; Travis 1993).

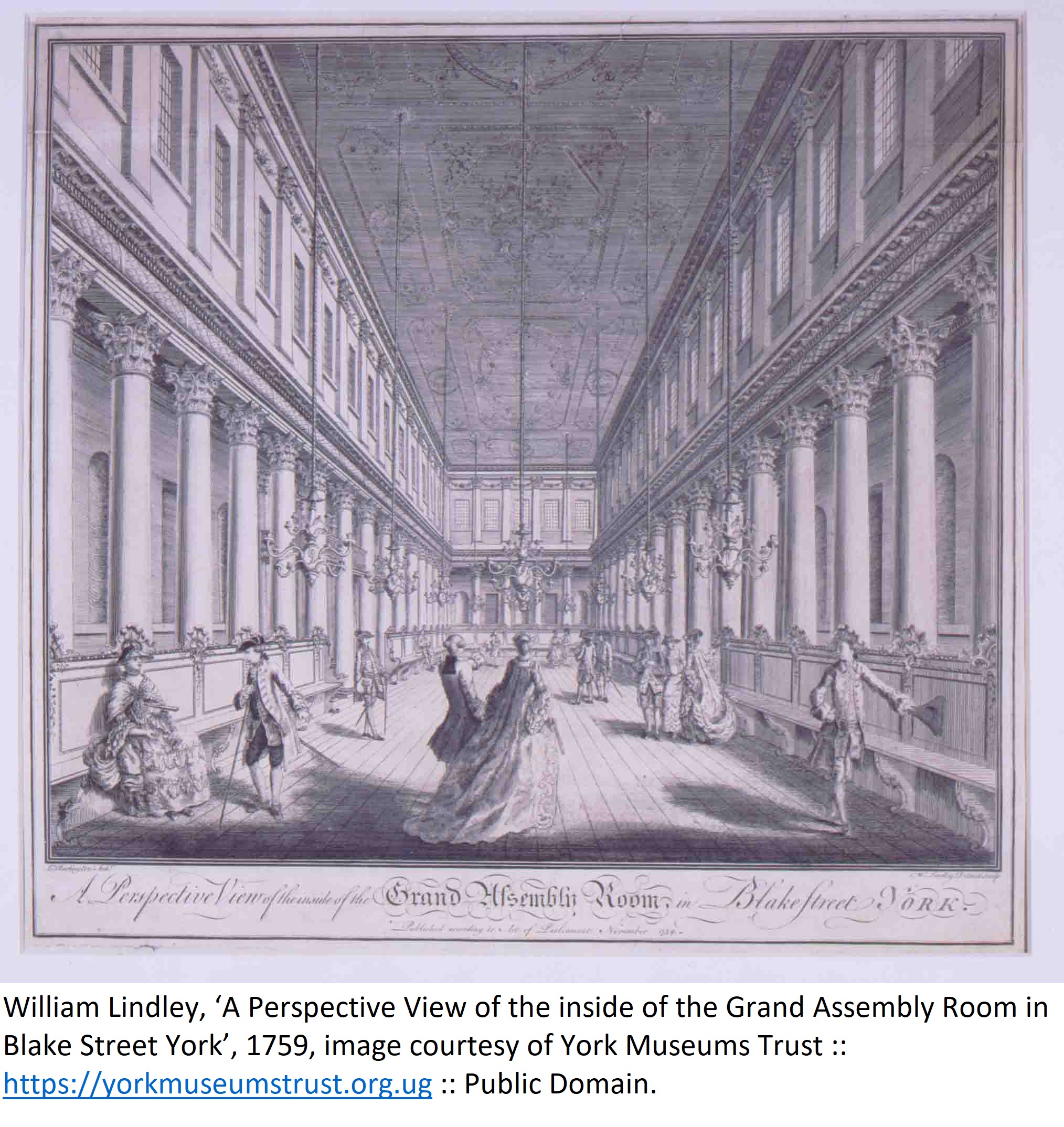

Assembly rooms tended to be constructed in a long rectangular format, permitting promenading and accommodating the parallel lines required for country dances. Bath’s Upper Rooms was one of the largest, being about 105 feet (32 metres) in length and 42 feet (13 metres) wide; by contrast, various assembly rooms at Cheltenham were 60-70 feet (18-21 metres) long and sometimes less than 30 feet (9 metres) wide (Hembry 1990). Amongst the earliest and most resplendent assembly rooms were those in York, built in the early 1730s to a design by Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, under a subscription scheme. The directors stipulated a large room for dancing, no smaller than 90 feet (27 metres) in length; a room for refreshments; and a room for cards. Burlington’s response was to create an ‘Egyptian Hall’ influenced by Palladio and Vitruvius as the Great Assembly Room, with a Lesser Assembly Room to the side which housed winter assemblies and concerts (Baines 1823; Tillott 1961). Spectators were usually accommodated on benches or tiers of chairs; unfortunately in York, their view was partially obstructed by Burlington’s columns and while later modifications improved the outlook, they simultaneously narrowed the available dance space (Girouard 1990).

Inns and Taverns

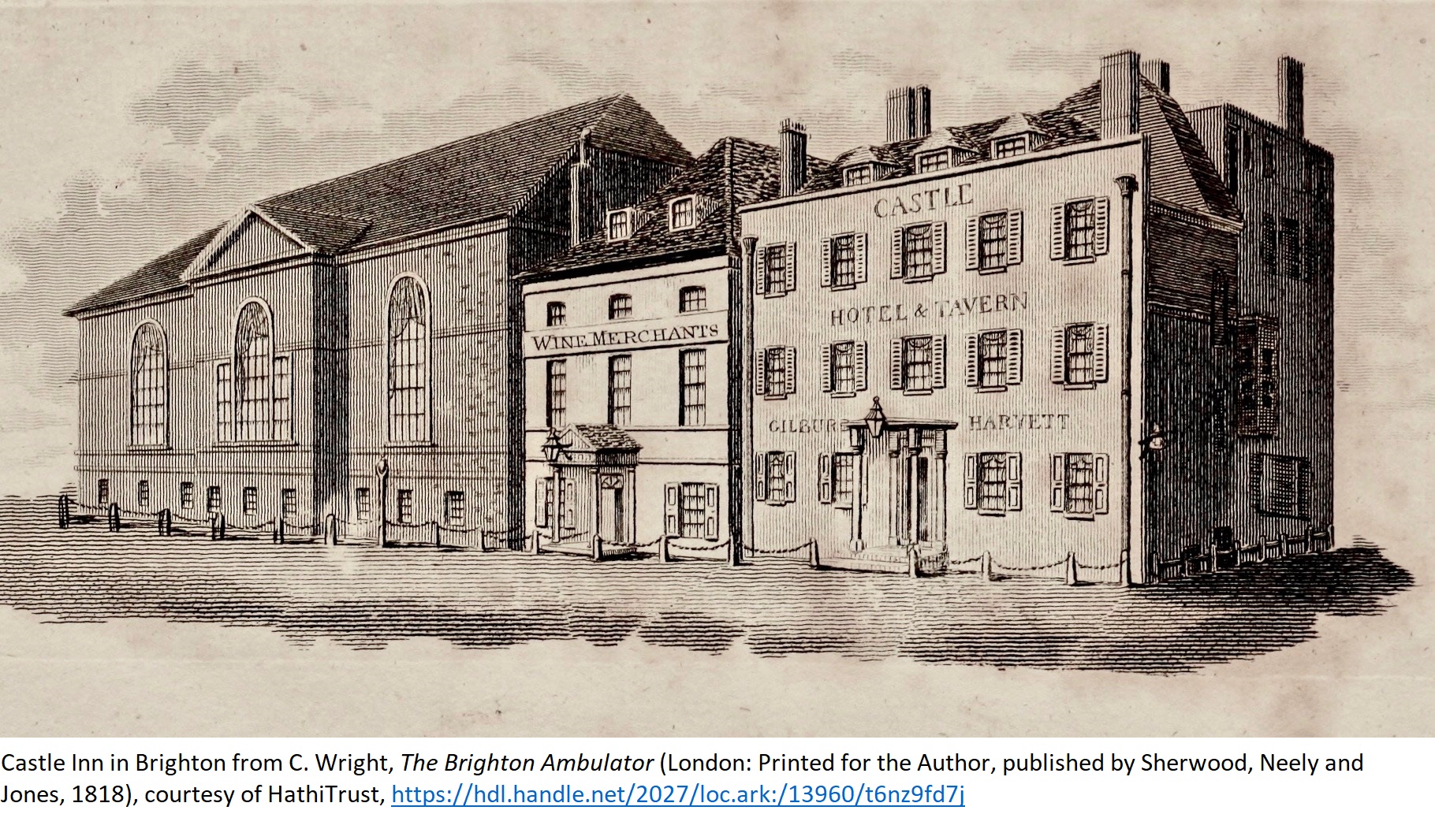

With a long established history, inns (later renamed as hotels) were one of the principal landmarks of eighteenth-century British towns, acting as important hubs for communal sociable gatherings and information exchange. Located at the top end of the hierarchy of licensed premises, inns were “enablers of the everyday”: they supplemented established civic services and buildings such as churches, coffee houses, libraries, theatres, auction houses, court rooms and town halls, and particularly in smaller towns they could take on these functions (Maudlin 2019, 618). As hosts of entertainment and sociable activities, inns variously catered for travelling shows and exhibitions, sports such as cock-fighting, clubs, political hustings and dance (Green 2015; Maudlin 2019). Many inns, either remodelled or newly built, included assembly rooms: the most exclusive, like the Castle Inn in Brighton, matched stand-alone assembly rooms in scope and décor (Berry 2013; Maudlin 2019); others, such as the Bowling Green Inn in Leamington, offered comparatively tiny spaces at just 30 feet (9 metres) long and 15 feet (4 metres) wide, or mustered low numbers of dancers, like the Old Eagle Inn in Buxton which saw just a dozen couples in 1789 (Hembry 1990). Some assembly rooms were placed at the heart of a new consumer experience: Buxton’s Crescent and Southampton’s incomplete Polygon Estate, both purpose-built endeavours, situated assembly rooms within hotels, surrounded by shops purveying elegant and luxury produce along with conveniences such as a circulating library (Collinge 2017; New Buxton Guide 1837; Temple Patterson 1970). In places like Harrogate, the tradition of dancing at inns at the expense of a dedicated assembly room continued well into the nineteenth century and appeared to be a source of local pride (Mitchinson 1994).

With a long established history, inns (later renamed as hotels) were one of the principal landmarks of eighteenth-century British towns, acting as important hubs for communal sociable gatherings and information exchange. Located at the top end of the hierarchy of licensed premises, inns were “enablers of the everyday”: they supplemented established civic services and buildings such as churches, coffee houses, libraries, theatres, auction houses, court rooms and town halls, and particularly in smaller towns they could take on these functions (Maudlin 2019, 618). As hosts of entertainment and sociable activities, inns variously catered for travelling shows and exhibitions, sports such as cock-fighting, clubs, political hustings and dance (Green 2015; Maudlin 2019). Many inns, either remodelled or newly built, included assembly rooms: the most exclusive, like the Castle Inn in Brighton, matched stand-alone assembly rooms in scope and décor (Berry 2013; Maudlin 2019); others, such as the Bowling Green Inn in Leamington, offered comparatively tiny spaces at just 30 feet (9 metres) long and 15 feet (4 metres) wide, or mustered low numbers of dancers, like the Old Eagle Inn in Buxton which saw just a dozen couples in 1789 (Hembry 1990). Some assembly rooms were placed at the heart of a new consumer experience: Buxton’s Crescent and Southampton’s incomplete Polygon Estate, both purpose-built endeavours, situated assembly rooms within hotels, surrounded by shops purveying elegant and luxury produce along with conveniences such as a circulating library (Collinge 2017; New Buxton Guide 1837; Temple Patterson 1970). In places like Harrogate, the tradition of dancing at inns at the expense of a dedicated assembly room continued well into the nineteenth century and appeared to be a source of local pride (Mitchinson 1994).

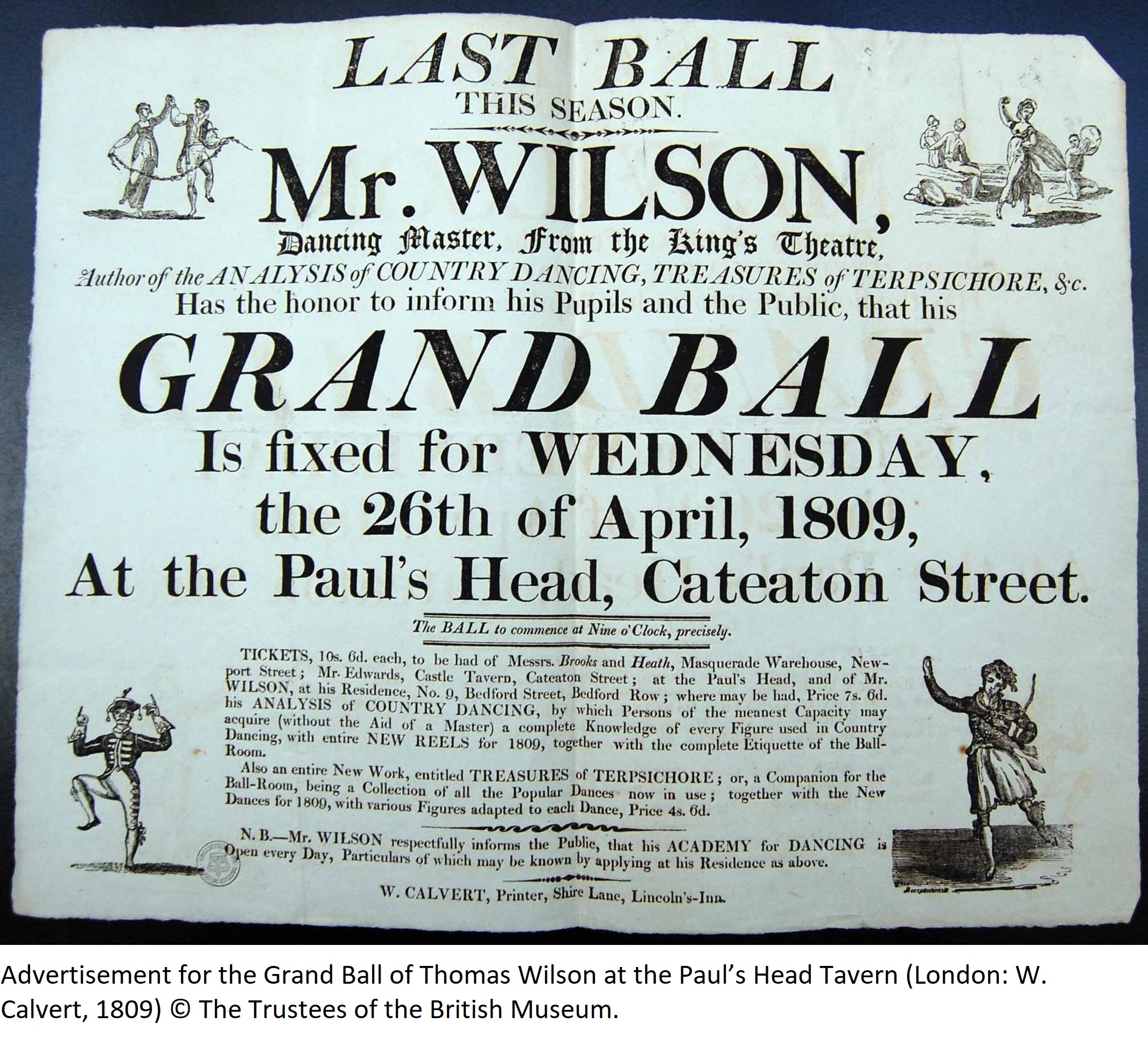

Like inns, taverns also accommodated a range of social and cultural functions. Drawing on a wealthier clientele than alehouses, taverns were popular dining-out venues, providing wine and hot food. In London, taverns outnumbered inns and were in direct competition for customers who didn’t require accommodation. They provided space for literary, political and philosophical discussions; business transactions; professional consultations; society meetings (including dancing masters); and book clubs, although some taverns less salubriously also catered for gambling and prostitutes. Taverns additionally hosted parties, lectures, concerts and balls (Lane 2018; Tardif 2002). The Academy of Ancient Music and the Anacreontic Society both met at the Crown and Anchor Tavern in London, the ballroom (concert room) of which was in excess of 80 feet (24 metres) long (McVeigh 1993). The Paul’s Head Tavern in Cateaton street hosted a number of concerts in the 1780s and 1790s, some of which also included balls. Outside of London, provincial assemblies were held in suitable spaces within taverns, while at Chatham barracks in Kent a ball was held at Hill House Tavern (formerly used as a navy Pay Office) to celebrate the birthday of King George III (Berry 2004; Cull 1962). In Edinburgh, David Budge announced he was reopening the London Coffeehouse also as a tavern, which included a “large room (which is only second to the Assembly Rooms in point of size and elegance)” to be let for balls, concerts and meetings (The Scotsman 21 May 1825).

Like inns, taverns also accommodated a range of social and cultural functions. Drawing on a wealthier clientele than alehouses, taverns were popular dining-out venues, providing wine and hot food. In London, taverns outnumbered inns and were in direct competition for customers who didn’t require accommodation. They provided space for literary, political and philosophical discussions; business transactions; professional consultations; society meetings (including dancing masters); and book clubs, although some taverns less salubriously also catered for gambling and prostitutes. Taverns additionally hosted parties, lectures, concerts and balls (Lane 2018; Tardif 2002). The Academy of Ancient Music and the Anacreontic Society both met at the Crown and Anchor Tavern in London, the ballroom (concert room) of which was in excess of 80 feet (24 metres) long (McVeigh 1993). The Paul’s Head Tavern in Cateaton street hosted a number of concerts in the 1780s and 1790s, some of which also included balls. Outside of London, provincial assemblies were held in suitable spaces within taverns, while at Chatham barracks in Kent a ball was held at Hill House Tavern (formerly used as a navy Pay Office) to celebrate the birthday of King George III (Berry 2004; Cull 1962). In Edinburgh, David Budge announced he was reopening the London Coffeehouse also as a tavern, which included a “large room (which is only second to the Assembly Rooms in point of size and elegance)” to be let for balls, concerts and meetings (The Scotsman 21 May 1825).

Public and Commercial Buildings

In the absence of dedicated assembly rooms or adequate space to house numerous patrons, assemblies and balls were held in a variety of largely public buildings. These included court houses, town and guildhalls, exchanges and schools, in addition to converted theatres (Girouard 1990; Stobart 2000). Some civic buildings contained purpose-built banqueting or ballrooms: Doncaster’s Mansion House, designed by James Paine in the 1740s, was conceived for municipal entertainment and featured a richly decorated ballroom that took up the entire width of the building (Leach 1978); Liverpool’s Town Hall, contemporary![R. Winkles after James Harwood, ‘Interior of the Ball-Room, Town-Hall’ [Liverpool] (London: Fisher, Son, & Co., 1839), RCIN 701726, Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021. R. Winkles after James Harwood, ‘Interior of the Ball-Room, Town-Hall’ [Liverpool] (London: Fisher, Son, & Co., 1839), RCIN 701726, Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021.](/sites/sound-heritage.soton.ac.uk/files/filefield_paths/r_winkles_after_james_harwood_interior_of_the_ball-room_town_hall_liverpool_1839_royal_collections_trust.jpg) with the Mansion House, was built with assembly rooms by John Wood and subsequently gained a large and small ballroom when extensions and rebuilding were undertaken in the late eighteenth century under James Wyatt (Pollard and Pevsner 2006). Such rooms also sometimes served more than one purpose: Newark’s Town Hall, designed by John Carr who oversaw the development of Buxton’s Crescent, had an assembly room that doubled as a court of law, in a multi-functional building that also included a corn exchange and butter market (Hall 1991). In London, places of entertainment such as Hickford’s Room, Carlisle House, the Pantheon, Hanover Square Rooms and Argyll Rooms were used for a multitude of purposes including concerts, balls, masquerades, exhibitions, demonstrations, lectures, readings and theatrical performances (Sheppard 1963, 1966; Walford 1878). These occurred at different points in their histories and despite sometimes significant associations with particular disciplines: even the King’s Theatre, home to Italian opera, hosted balls from the early eighteenth century through into Queen Victoria’s reign (Barnett Smith 1887; Burden 2019; Semmens 2004).

with the Mansion House, was built with assembly rooms by John Wood and subsequently gained a large and small ballroom when extensions and rebuilding were undertaken in the late eighteenth century under James Wyatt (Pollard and Pevsner 2006). Such rooms also sometimes served more than one purpose: Newark’s Town Hall, designed by John Carr who oversaw the development of Buxton’s Crescent, had an assembly room that doubled as a court of law, in a multi-functional building that also included a corn exchange and butter market (Hall 1991). In London, places of entertainment such as Hickford’s Room, Carlisle House, the Pantheon, Hanover Square Rooms and Argyll Rooms were used for a multitude of purposes including concerts, balls, masquerades, exhibitions, demonstrations, lectures, readings and theatrical performances (Sheppard 1963, 1966; Walford 1878). These occurred at different points in their histories and despite sometimes significant associations with particular disciplines: even the King’s Theatre, home to Italian opera, hosted balls from the early eighteenth century through into Queen Victoria’s reign (Barnett Smith 1887; Burden 2019; Semmens 2004).

Barracks

Throughout the eighteenth century it was common for regiments to be billeted across England, who utilised local amenities such as assembly rooms, inns and halls when hosting balls. However, due to the threat of invasion from France and potential civic unrest, barrack accommodation became increasingly necessary, leading to the provision of entertainment onsite (May 2002). In 1805 Mary Nash wrote from Ipswich describing how “we are very sorry to leave our very agreeable friends ![‘Royal Artillery Barracks’ [Woolwich] (London: John Baker, 19th century) © The Trustees of the British Museum. ‘Royal Artillery Barracks’ [Woolwich] (London: John Baker, 19th century) © The Trustees of the British Museum.](/sites/sound-heritage.soton.ac.uk/files/filefield_paths/royal_artillery_barracks_woolwich_john_baker_19th_century_british_museum.jpg) of the Royal East Middlesex who seem equaly [sic] sorry to part with us & are now busy in giving the girls take leave dances & partys, their Barrack is a scene of Gaiety & very elegant balls & suppers & 2 eveng partys have already been given” (Herbert and Barlow 2013, 117). While some barracks were constructed from pre-existing buildings, such as breweries, inns and warehouses, others were purpose-built (Douet 1998; May 2002). Within the barracks, the officers’ mess was “modelled…on the atmosphere and practices of a gentlemen’s club…allow[ing] officers to drink, dine and socialise in a style that marked them as socially superior to their men” and it was in the mess where balls were often held (Barlow 2016, 83). The Royal Artillery Barracks in Woolwich, one of the largest barracks in Britain, featured an officers’ mess designed by James Wyatt as part of significant building works undertaken in the early nineteenth century; the mess was used for a ball in 1816, when it was reported to be 60 feet (18 metres) by 50 feet (15 metres) in size (Guillery 2012). Other mess rooms were also used for balls at Chatham and at Richmond Barracks in Dublin. Reverse manoeuvres also took place in which dancing spaces were converted into military use - in Plymouth, the Long Room assembly room was acquired by Stonehouse Barracks in 1805 when it was converted into an officers’ mess, while at Woolwich the spectacular rotunda from the Prince Regent’s fête, held at Carlton House in 1814 where it served as a ballroom measuring 110 feet (34 metres) in diameter, was repurposed as a military museum (Historic England, n.d.; Guillery 2012).

of the Royal East Middlesex who seem equaly [sic] sorry to part with us & are now busy in giving the girls take leave dances & partys, their Barrack is a scene of Gaiety & very elegant balls & suppers & 2 eveng partys have already been given” (Herbert and Barlow 2013, 117). While some barracks were constructed from pre-existing buildings, such as breweries, inns and warehouses, others were purpose-built (Douet 1998; May 2002). Within the barracks, the officers’ mess was “modelled…on the atmosphere and practices of a gentlemen’s club…allow[ing] officers to drink, dine and socialise in a style that marked them as socially superior to their men” and it was in the mess where balls were often held (Barlow 2016, 83). The Royal Artillery Barracks in Woolwich, one of the largest barracks in Britain, featured an officers’ mess designed by James Wyatt as part of significant building works undertaken in the early nineteenth century; the mess was used for a ball in 1816, when it was reported to be 60 feet (18 metres) by 50 feet (15 metres) in size (Guillery 2012). Other mess rooms were also used for balls at Chatham and at Richmond Barracks in Dublin. Reverse manoeuvres also took place in which dancing spaces were converted into military use - in Plymouth, the Long Room assembly room was acquired by Stonehouse Barracks in 1805 when it was converted into an officers’ mess, while at Woolwich the spectacular rotunda from the Prince Regent’s fête, held at Carlton House in 1814 where it served as a ballroom measuring 110 feet (34 metres) in diameter, was repurposed as a military museum (Historic England, n.d.; Guillery 2012).

Outside Spaces

Across the eighteenth century Britain’s urban outdoor spaces adopted a growing formalisation of design in their pursuit of publicly accessible recreation and leisure. Pleasure gardens were one aspect of this movement and sat beside other venues such as assembly rooms, theatres and coffeehouses in “delivering commercialized urban public culture on an unprecedented scale” (Borsay 2013, 50). An important source of amusement and novelty especially during the summer, many pleasure gardens incorporated Great or Long rooms which catered for music and dance, although some provided dancing platforms with partial covering (Wroth 1979). Iconography suggests that dancing also took place completely out in the open. London’s most spectacular pleasure gardens came up with more extravagant solutions: the rotunda at Ranelagh, which accommodated undercover promenading as well as balls, masquerades and concerts, was around 150 feet (46 metres) in diameter internally and was lavishly decorated and illuminated (Borsay 2013; Doderer-Winkler 2013); Vauxhall had a Great Room attached to the Prince’s Pavilion and a rotunda which was a mere 68 feet (20 metres) in comparison, although it seemingly wasn’t used for dancing until the nineteenth century (Coke and Borg 2011). In addition to more permanent infrastructure, pleasure gardens also used temporary buildings to act as ballrooms: the Vauxhall jubilee in 1786 saw the construction of two ballrooms of 80 feet (24 metres) in length attached to a Grand Temple (Coke and Borg 2011); the Festivale di Campagna at Marylebone Gardens ten years earlier contained a Temple of Apollo, in which country dancing was purportedly interrupted by arguments and fire (Sands 1987); and Ranelagh showed off an unfinished naval themed Temple of Neptune as part of a regatta entertainment in 1775 which appeared to be little short of an unmitigated disaster, marred by poor weather, mismanagement and general chaos (O’Quinn 2011).

assembly rooms, theatres and coffeehouses in “delivering commercialized urban public culture on an unprecedented scale” (Borsay 2013, 50). An important source of amusement and novelty especially during the summer, many pleasure gardens incorporated Great or Long rooms which catered for music and dance, although some provided dancing platforms with partial covering (Wroth 1979). Iconography suggests that dancing also took place completely out in the open. London’s most spectacular pleasure gardens came up with more extravagant solutions: the rotunda at Ranelagh, which accommodated undercover promenading as well as balls, masquerades and concerts, was around 150 feet (46 metres) in diameter internally and was lavishly decorated and illuminated (Borsay 2013; Doderer-Winkler 2013); Vauxhall had a Great Room attached to the Prince’s Pavilion and a rotunda which was a mere 68 feet (20 metres) in comparison, although it seemingly wasn’t used for dancing until the nineteenth century (Coke and Borg 2011). In addition to more permanent infrastructure, pleasure gardens also used temporary buildings to act as ballrooms: the Vauxhall jubilee in 1786 saw the construction of two ballrooms of 80 feet (24 metres) in length attached to a Grand Temple (Coke and Borg 2011); the Festivale di Campagna at Marylebone Gardens ten years earlier contained a Temple of Apollo, in which country dancing was purportedly interrupted by arguments and fire (Sands 1987); and Ranelagh showed off an unfinished naval themed Temple of Neptune as part of a regatta entertainment in 1775 which appeared to be little short of an unmitigated disaster, marred by poor weather, mismanagement and general chaos (O’Quinn 2011).

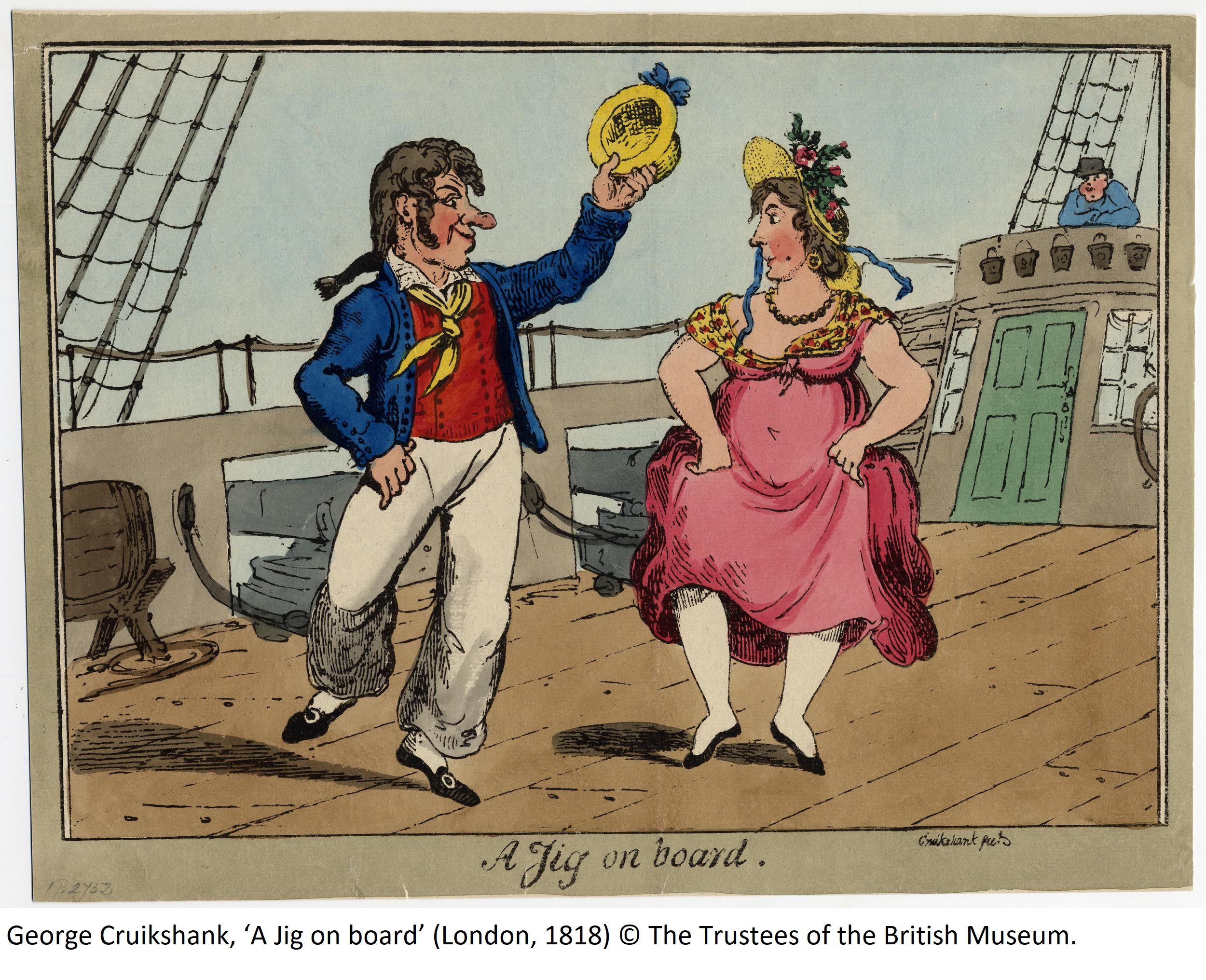

The procession of the regatta down the Thames to Ranelagh mirrored the journey many visitors took to access the pleasure gardens, water transport being convenient and preferable to a traffic jam on the roads (Borsay 2013). The increase in fashionable pleasure boating and racing in the eighteenth century saw many take to the water for parties of leisure or as floating spectators for regattas, sometimes in considerable numbers (Cusack 1996). Such journeys could be accompanied by music but water craft were also a location for dance. The Union yacht belonging to the Sharp family, one of the most notable groups of musicians on the water, was used as a mobile home over the summer months where their aquatic entertainments included some of London’s most eminent performers. The catalogue for the yacht’s sale in 1786 detailed substantial living quarters – the boat itself measured 70 feet (21 metres) long and 13 ½ feet (4 metres) wide and the main deck could be turned into a ballroom when the awning was deployed (Crosby 2001). Dance also featured in more public arrangements. To celebrate the completion of the Paddington canal in 1801, a barge carrying the inaugural passengers from Uxbridge hosted music and dance until midnight. An earlier, more permanent incarnation called “The Folly”, a castellated saloon on a barge, was moored on the Thames during the summer where ladies could be seen dancing on the deck (Wroth 1979). Further offshore, naval personnel danced on the quarter deck, often under moonlight and sometimes boisterously (Rodger 2005; O’Keeffe 2018); on slave ships, “dancing the slaves” also took place on deck, a form of forced exercise under threat of physical abuse designed to maintain health and wellbeing, which also acted as an entertainment for ship guests (Emery 1972).

The procession of the regatta down the Thames to Ranelagh mirrored the journey many visitors took to access the pleasure gardens, water transport being convenient and preferable to a traffic jam on the roads (Borsay 2013). The increase in fashionable pleasure boating and racing in the eighteenth century saw many take to the water for parties of leisure or as floating spectators for regattas, sometimes in considerable numbers (Cusack 1996). Such journeys could be accompanied by music but water craft were also a location for dance. The Union yacht belonging to the Sharp family, one of the most notable groups of musicians on the water, was used as a mobile home over the summer months where their aquatic entertainments included some of London’s most eminent performers. The catalogue for the yacht’s sale in 1786 detailed substantial living quarters – the boat itself measured 70 feet (21 metres) long and 13 ½ feet (4 metres) wide and the main deck could be turned into a ballroom when the awning was deployed (Crosby 2001). Dance also featured in more public arrangements. To celebrate the completion of the Paddington canal in 1801, a barge carrying the inaugural passengers from Uxbridge hosted music and dance until midnight. An earlier, more permanent incarnation called “The Folly”, a castellated saloon on a barge, was moored on the Thames during the summer where ladies could be seen dancing on the deck (Wroth 1979). Further offshore, naval personnel danced on the quarter deck, often under moonlight and sometimes boisterously (Rodger 2005; O’Keeffe 2018); on slave ships, “dancing the slaves” also took place on deck, a form of forced exercise under threat of physical abuse designed to maintain health and wellbeing, which also acted as an entertainment for ship guests (Emery 1972).

Houses and Landscapes

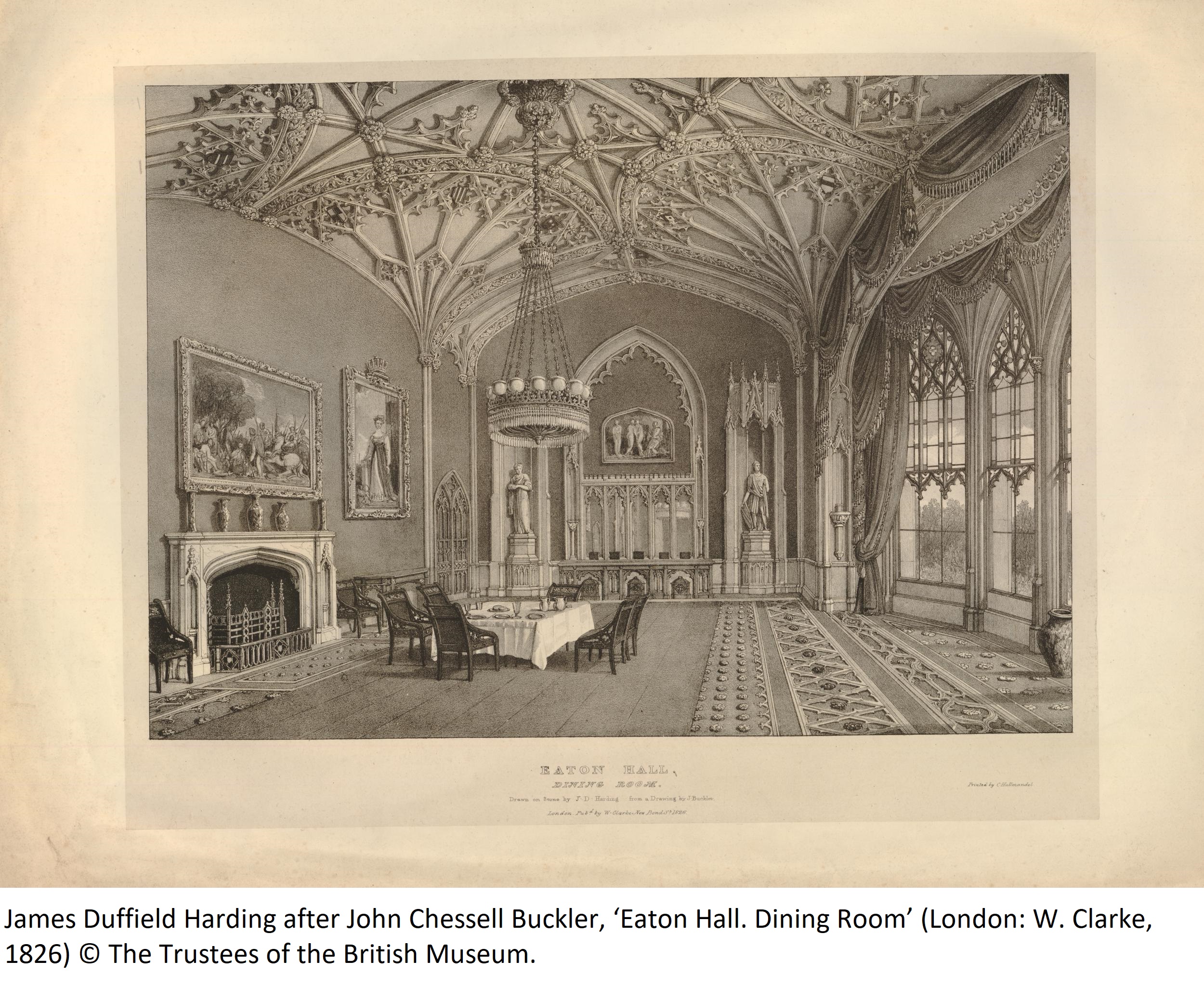

An increasing number of balls also took place in private houses, somewhat usurping the need for assembly rooms (Girouard 1990). While some stately homes had specified ballrooms, such as Goodwood House and Hackwood Park, many catered for dance by flexibly appropriating other rooms. In 1799, Mary Jemima Robinson, Lady Grantham, described “a very handsome ball” where “the ball room was the Library near fifty feet [15 metres] long, but from its lengh [sic], height, & a very fine lustre to light it, was just as well calculated for its temporary purpose” (Bedfordshire Archives L30/11/240/84). At Panshanger a juvenile ball was held in the picture gallery where the dancers were surrounded by “the finest paintings by the old Masters” (Morning Post 22 January 1824). Different rooms could be used for different purposes: tenants’ balls at Eaton Hall in the 1820s took place in the tenants’ hall, which was variously reported as being between 64 and 130 feet (19 to 40 metres) in length, whereas for the meeting of the Royal British Bowmen dancing was in the dining room and the tenants’ hall was relegated to supper. At the other end of the spectrum, Jane Austen’s mother anticipated “a very snug little dance in our parlour, just our own children, nephew & nieces” (Le Faye 2002, 75). Dancing also occurred in the nether regions of houses. At Dunham Massey, servant dances took place in the servants’ hall, but during wedding celebrations in 1825 the dancing migrated from the steward’s room into the Great Hall (Sambrook 2003).

An increasing number of balls also took place in private houses, somewhat usurping the need for assembly rooms (Girouard 1990). While some stately homes had specified ballrooms, such as Goodwood House and Hackwood Park, many catered for dance by flexibly appropriating other rooms. In 1799, Mary Jemima Robinson, Lady Grantham, described “a very handsome ball” where “the ball room was the Library near fifty feet [15 metres] long, but from its lengh [sic], height, & a very fine lustre to light it, was just as well calculated for its temporary purpose” (Bedfordshire Archives L30/11/240/84). At Panshanger a juvenile ball was held in the picture gallery where the dancers were surrounded by “the finest paintings by the old Masters” (Morning Post 22 January 1824). Different rooms could be used for different purposes: tenants’ balls at Eaton Hall in the 1820s took place in the tenants’ hall, which was variously reported as being between 64 and 130 feet (19 to 40 metres) in length, whereas for the meeting of the Royal British Bowmen dancing was in the dining room and the tenants’ hall was relegated to supper. At the other end of the spectrum, Jane Austen’s mother anticipated “a very snug little dance in our parlour, just our own children, nephew & nieces” (Le Faye 2002, 75). Dancing also occurred in the nether regions of houses. At Dunham Massey, servant dances took place in the servants’ hall, but during wedding celebrations in 1825 the dancing migrated from the steward’s room into the Great Hall (Sambrook 2003).

Like the pleasure gardens, some households utilised temporary structures for dance. The Wentworth family erected a temporary ballroom, some 70 feet (21 metres) long and decorated by the Italian artist Agostino Aglio, at Woolley Hall in 1818, while Edward Smith Stanley, future 12th Earl of Derby, installed a magnificent stand-alone pavilion created by Robert Adam in 1774 which contained a ballroom measuring 4200 square feet (390 square metres) and a supper room (Nelson 1999). Moving further outdoors, dance took place in portable tents and sometimes entirely out in the open. A choice example which combined several dance locations was Lady Cardigan’s fête at her Richmond house, held to celebrate the Prince Regent’s birthday in 1817: wet weather scuppered the original plan to dance “in the open air, or in one of Tippo [sic] Saib’s tents, borrowed and pitched there for the occasion”, so the dining room was transformed into a ballroom, while the Lord Mayor (who was stationed on a barge) hosted country dancing for those on board, viewed by Lady Cardigan’s guests (The Times 14 August 1817).