Arrangements: Melodies, Accompaniments and the Problem of Originality

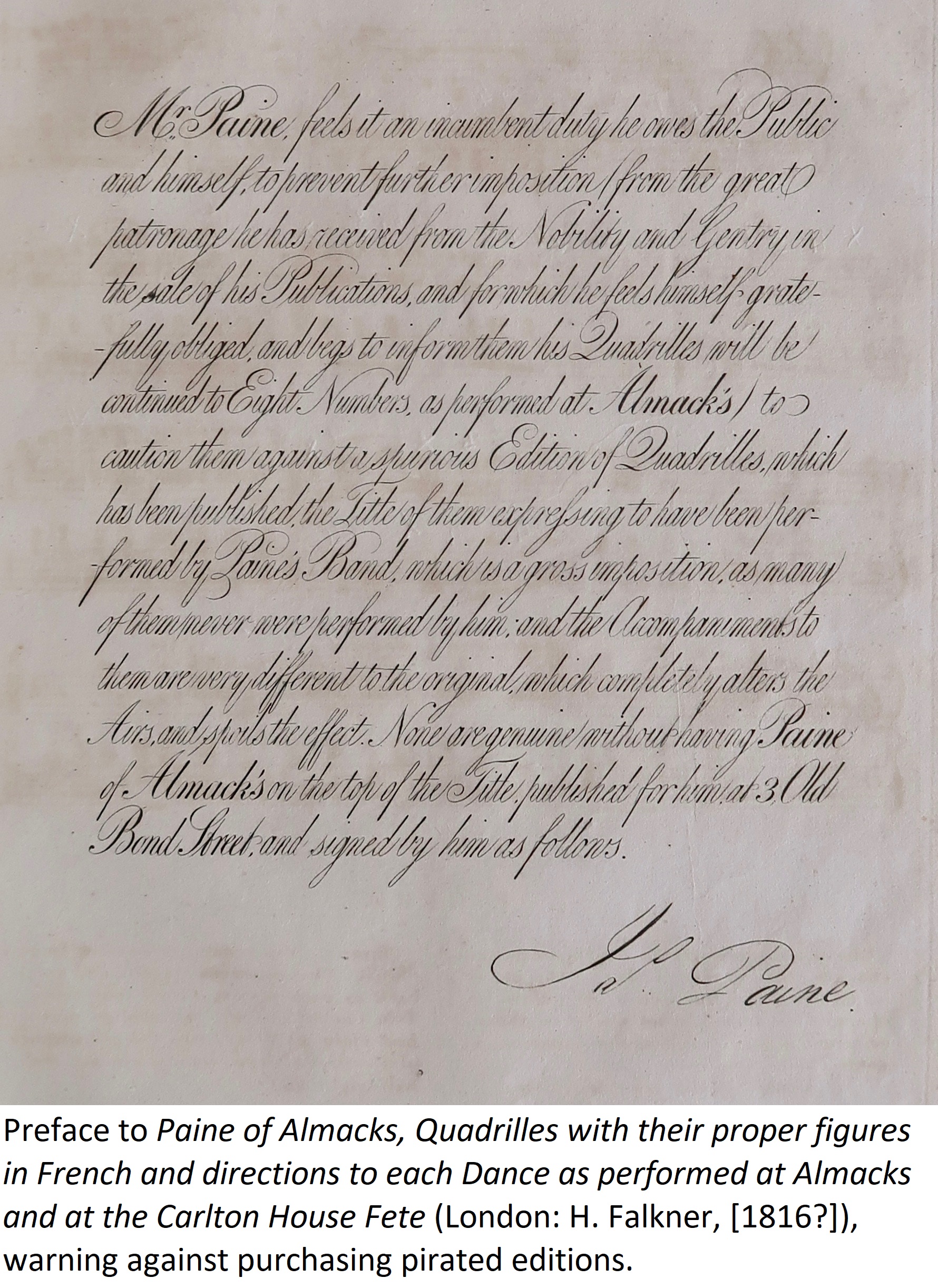

In a preface attached to several editions of his quadrille music, band leader James Paine railed against “a spurious Edition of Quadrilles”, which claimed on the title page “to have been performed by Paine’s Band, which is a gross imposition, as many of them never were performed by him; and the Accompaniments to them are very different to the original, which completely alters the Airs, and spoils the effect”.

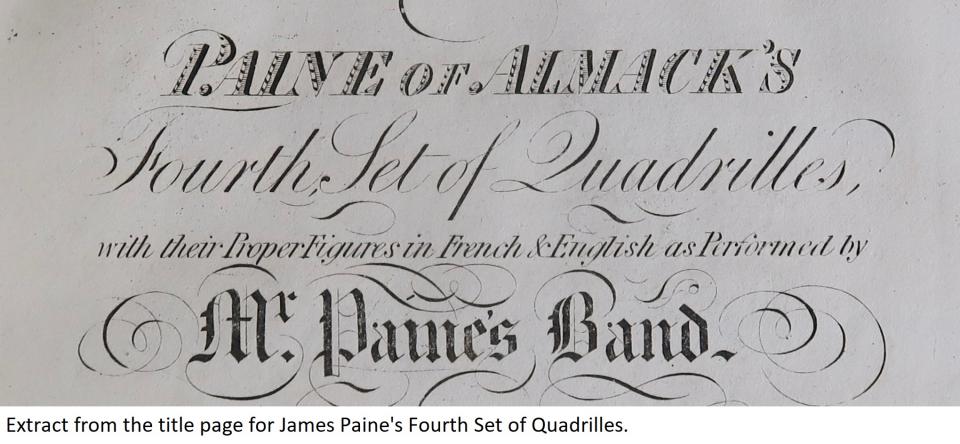

Paine had good reason to be annoyed, as at least three different publishers produced variants of Paine’s quadrilles, all bearing similarly-worded title pages referencing his band, ready to baffle unwitting purchasers (Cooper 2015). He was, of course, attempting to protect his commercial interests: as leader of one of the most prominent dance bands in London which performed at one of the capital’s most exclusive venues – Almack’s Assembly Rooms – Paine’s music was a valuable cultural commodity. His comment about accompaniments, however, raises important questions about the broader issues concerning arrangement practices and dissemination.

Paine had good reason to be annoyed, as at least three different publishers produced variants of Paine’s quadrilles, all bearing similarly-worded title pages referencing his band, ready to baffle unwitting purchasers (Cooper 2015). He was, of course, attempting to protect his commercial interests: as leader of one of the most prominent dance bands in London which performed at one of the capital’s most exclusive venues – Almack’s Assembly Rooms – Paine’s music was a valuable cultural commodity. His comment about accompaniments, however, raises important questions about the broader issues concerning arrangement practices and dissemination.

Paine’s quadrille publications are, of necessity, arrangements of instrumental performances given by his band, and without original scores or parts it is impossible to know how closely the instrumental accompaniments mapped onto the published versions for harp or piano. His melodies appear to be original, even though the dancing master Thomas Wilson suggested “the tunes have mostly been selected, Or altered so to hide from whence collected” (Wilson 1824, 200). A copy of Paine’s first set of quadrilles for piano or harp published by Chappell & Co. around a year or two after the original version for piano, harp or violin appears to leave the melody intact but differs greatly in the articulation of the accompaniment, with many changes to register, rhythm, accentuation and effect. It is difficult to tell if Paine was just upset about the unauthorised reimagining of his music, whether these sorts of subtleties were important to how both the music and his band were perceived, or whether he thought they impacted negatively on the actual dance itself. His complaint suggests that the accompaniments were crucial in contributing to musical character and that alterations therein indelibly shifted the music’s meaning and effect.

The issue of accompaniments becomes stickier when considering how Paine’s music was used more broadly. While his quadrille publications obviously served the domestic market, it is likely that they were also used by professionals. A dancing master in Nottingham advertised in 1819 that “the whole of his Pupils are taught Paine of Almack’s Sets of Quadrilles” (Nottingham Review 22 January 1819). As the published dance figures altered little across Paine’s oeuvre, this was likely to be less about dance and more about musical familiarisation unless alternative figures were taught. It’s clear that Paine’s music was also performed by other dance bands – an advertisement placed in the Newcastle Courant on 16 October 1819 by George Elliot, who described himself as a leader at local assemblies, made a point of mentioning that his band was “practised in Quadrilles (including the whole of Paine of Almacks)”. It’s unknown whether Elliot obtained copies of parts or whether the band created their own arrangements from the published versions. Certainly they would not have been the only band to do so and Paine could have had little control over how his music was subsequently arranged or performed, including the critical accompaniments.

Paine was not the only band leader who was protective of his band and his music. Piqued by the suggestion that music performed at Almack’s was subsequently played at another fashionable ball by a rival quadrille band, the flageolet player Hubert Collinet launched a polite but stinging attack in the Morning Post:

"The Band at ALMACK’s, conducted by Messrs. MICHAU, MUSARD, and COLLINET, has no connection with any other. It has but just arrived from Paris, purposely for ALMACK’s Balls, with a collection of new Quadrilles, Waltzes, &c., as arranged and composed by them; and…it is totally out of the power of any other persons to procure and perform such new Quadrilles as played at the first ALMACK’s Assembly" (27 April 1830).

Although possibly a case of confusion by the newspaper, Collinet’s notice gives an indication of how tightly bands initially clung to their music and possibly how their proprietorship extended to the arrangements themselves, including the accompaniments. If Collinet’s band really did play at the preceding Almack’s ball, his point was moot, as a large proportion of the music was in fact derived from French and Italian opera (Morning Post 23 April 1830), meaning that any claim to exclusive authorship essentially rested on the nature of the arrangements.

Although possibly a case of confusion by the newspaper, Collinet’s notice gives an indication of how tightly bands initially clung to their music and possibly how their proprietorship extended to the arrangements themselves, including the accompaniments. If Collinet’s band really did play at the preceding Almack’s ball, his point was moot, as a large proportion of the music was in fact derived from French and Italian opera (Morning Post 23 April 1830), meaning that any claim to exclusive authorship essentially rested on the nature of the arrangements.

Collinet’s comment that “it is totally out of the power of any other persons to procure and perform such new Quadrilles” needs to be weighed against the general availability of theatrical music. Clearly many composers exploited the commercial possibilities of writing dance music based on successful stage productions, including Collinet’s band colleague, Philippe Musard. They were, of course, free to utilise any tunes they liked from operas and ballets in their concoctions, provided there was no infringement of copyright, and this is where the rub lies for Collinet. What separated one set of quadrilles from another based on the same composition essentially lay in the choice of extracts, and the way the arrangement was managed with respect to instrumentation, register and accompaniment, for both bands and domestic consumers. In the case of the latter, this feeds into issues of consumer preference and skill, especially as the instrumentation was fairly uniform in published arrangements. Musard’s involvement in copyright litigation for sets of opera quadrilles five years later ultimately placed considerable weight on melodic invention as being key to establishing creative authorship (Lockhart 2012), but in a competitive field of arrangers, accompaniments clearly contributed to the success of an arrangement and potentially also to a band’s sound, thus having both a musical and commercial value.

Further Reading:

Cooper, Paul. 2015. “James Paine, of Almack’s (1778-1855).” January 16, 2015. https://www.regencydances.org/paper010.php

Lockhart, William. 2012. “Trial by Ear: Legal Attitudes to Keyboard Arrangement in Nineteenth-Century Britain.” Music & Letters 93, no. 2 (May): 191-221.

Wilson, Thomas. 1824. The Danciad; or, Dancer’s Monitor. London: Printed for the Author.