Dance Music Sources and Dissemination

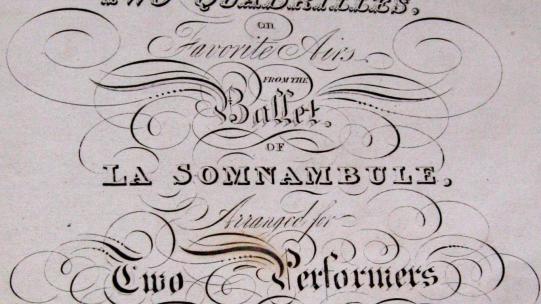

Dance music was one of the backdrops to social life in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. At balls, a variety of dance bands played music for people to dance to. However, many of the scores and parts belonging to these bands appear not to have survived. Instead, dance music largely exists in printed publications aimed at the domestic market – this provided a significant route for distribution across the country and forms the basis for our understanding of dance music today. Such publications were commonly advertised for performance on keyboard or harp, or for solo instruments such as the flute, violin or oboe.

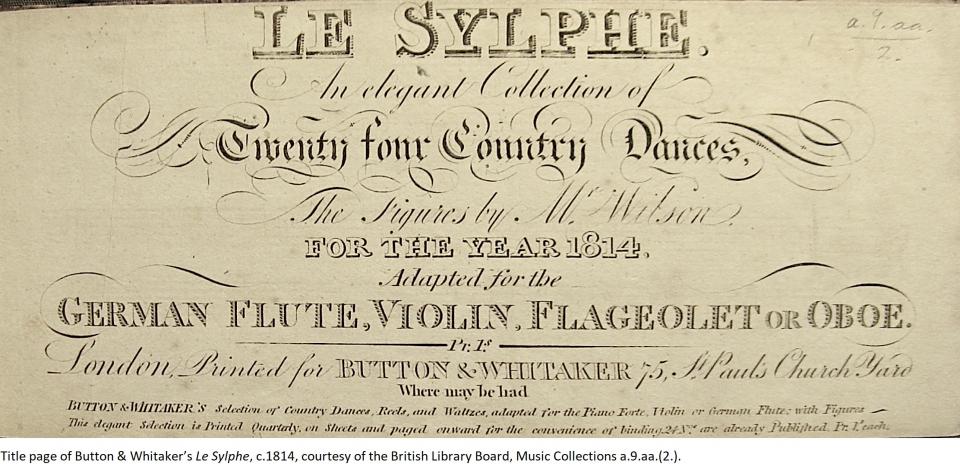

One of the most popular printed formats in the eighteenth century was the annual collection, a grouping of dances published in advance of the forthcoming social season for a given year (Brainard 1998). These small oblong publications were highly portable and inexpensive, often consisting of single melody lines (sometimes with an additional bass accompaniment) with dance figures indicated in a type of shorthand. Collections of minuets and country dances were common, but several types of dances could be combined in a single publication. Sometimes annual collections were printed on dance fans and playing cards, while instructions for dances were also printed in pocket diaries (Hyatt King 1983).

One of the most popular printed formats in the eighteenth century was the annual collection, a grouping of dances published in advance of the forthcoming social season for a given year (Brainard 1998). These small oblong publications were highly portable and inexpensive, often consisting of single melody lines (sometimes with an additional bass accompaniment) with dance figures indicated in a type of shorthand. Collections of minuets and country dances were common, but several types of dances could be combined in a single publication. Sometimes annual collections were printed on dance fans and playing cards, while instructions for dances were also printed in pocket diaries (Hyatt King 1983).

Some published dances – albeit a small proportion – were scored for instrumental ensembles of varying sizes. Several drew on the tradition of printed military music, in which marches and dances were scored for a band but often incorporated a keyboard part at the bottom of the stave for domestic audiences. As the nineteenth century progressed, parts for orchestra and military bands were published more frequently, as arrangements of quadrilles, galops and polkas became part of the concert repertoire (Herbert and Barlow 2013).

Dance music also circulated in manuscript form within professional and amateur arenas. Manuscript copybooks belonging to men and women often included dances with or without figures, sometimes alongside other instrumental compositions and vocal repertoire. While some clearly contained a pedagogical element, others, such as the mid-nineteenth-century tunebooks owned by Michael Turner, are likely indicative of practical communal music-making. Turner was a shoemaker, parish clerk and sexton at Warnham, who appears to have led the church choir and possibly also the band, but he was additionally known for playing for local dances (Gammon 1976).

Dance music was also disseminated by dance bands as they travelled across the country. The best bands were employed for balls hosted by royalty and elite families in London, but they also performed in provincial areas – James Paine’s band, for example, played for Christmas balls in Reading and Guildford; an annual ball given by cricket club members in Watlington; and a charity ball in Stamford. He also travelled to Hertfordshire, Cambridge and as far afield as Wales. In the autumn and winter of 1829, John Weippert’s band visited towns in Shropshire, Bedfordshire, Essex, Dorset, Hampshire and Wiltshire, amongst others, in what amounted to a promotional tour of a new set of quadrilles. These bands’ mobility helps us to see the wide reach of popular dance music beyond major cities and suggests that by the early nineteenth century bands would develop their own particular sound.

Further Reading:

Brainard, Ingrid. 1998. "Annual Collections." In The International Encyclopedia of Dance, edited by Selma Jeanne Cohen, vol. 1. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gammon, Vic. 1976. “Michael Turner: A 19th Century Sussex Fiddler.” Traditional Music 4: 14-23.

Herbert, Trevor, and Helen Barlow. 2013. Music & the British Military in the Long Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hyatt King, Alec. 1983. A Wealth of Music in the Collections of the British Library (Reference Division) and the British Museum. London: Clive Bingley.

Newspaper references:

Paine’s balls: Morning Post 8 February 1819 (Kent); Morning Post 12 July 1819 (Cambridge); Northampton Mercury 4 January 1823 (Stamford); Sun 15 September 1824 (Wales); Morning Post 11 October 1824 (Hertfordshire); Oxford University and City Herald 26 November 1825 (Watlington); Berkshire Chronicle 24 December 1825 (Reading); Windsor and Eton Express 31 December 1825 (Guildford).

Weippert’s balls: Morning Post 21 September 1829 (Shropshire); 14 November 1829 (Hampshire & Dorset); 16 November 1829 (Essex & Wiltshire); 17 December 1829 (Bedfordshire).