Performing Practices Lost and Found

What do we know about the performance practice of dance music around 1800? What sources do we have and what do they tell us? Across the pages of this website, we have provided a range of resources that together shape a picture of dance as it was practised in domestic spaces across Britain and how this related to dance in the public arena. The boundaries between the private and the public are blurry not least because the music that was played at public balls has been preserved largely in sheet music collections aimed at the domestic market: in keyboard arrangements or in collections of melodies. Little dance music survives in full score for instrumental ensembles or large bands. Left only with the countless tunes, we must wonder what this music actually sounded like in practice.

The sound of dance music around 1800 was determined by a range of factors: the instrumentation used to perform it and its orchestration, i.e. how these instruments were combined; whether performers would have played the music as written, whether players embellished key moments or whether they even extemporised entire parts; to what degree variation would have happened across the many repeats that much of the dance music requires; what the instruments themselves sounded like and, of course, what tempi and characters the dancers required.

Sources

Historical sources that could provide some answers include a host of images, yet this iconographical evidence is notoriously slippery. Images require careful decoding with attention to aspects such as the nature or genre of the image itself. Instruments in pictures can be particularly difficult as sources for performance practice because throughout history musical instruments possessed variously an animistic component or a symbolic function. A well-known example is the depiction of Lady Salisbury playing the horn in James Gillray’s The Pic-Nic Orchestra (1802), which served the dual purpose of illustrating her love for and association with hunting as well as signifying her eccentric character as women did not customarily play the horn. In William Humphrey’s print High Life Below Stairs the horn is used as a symbol of disruption or warning but offers little advice on a realistic musical scenario (Odumosu 2017). In addition, we need to question how reliable a painter’s attention to detail was when depicting, say, a ball. Did he simply want to show off the size of the band regardless of its exact make-up? Perhaps a particular instrument simply looked pretty as an addition to the image, or the painter sought to capture a variety of instruments rather than the specifics of a particular band on a particular occasion. One thing that these images do tell us, however, is that there was huge variety in the sizes and the make-up of bands; these we have documented in Dance Instrumentation in Britain.

Historical sources that could provide some answers include a host of images, yet this iconographical evidence is notoriously slippery. Images require careful decoding with attention to aspects such as the nature or genre of the image itself. Instruments in pictures can be particularly difficult as sources for performance practice because throughout history musical instruments possessed variously an animistic component or a symbolic function. A well-known example is the depiction of Lady Salisbury playing the horn in James Gillray’s The Pic-Nic Orchestra (1802), which served the dual purpose of illustrating her love for and association with hunting as well as signifying her eccentric character as women did not customarily play the horn. In William Humphrey’s print High Life Below Stairs the horn is used as a symbol of disruption or warning but offers little advice on a realistic musical scenario (Odumosu 2017). In addition, we need to question how reliable a painter’s attention to detail was when depicting, say, a ball. Did he simply want to show off the size of the band regardless of its exact make-up? Perhaps a particular instrument simply looked pretty as an addition to the image, or the painter sought to capture a variety of instruments rather than the specifics of a particular band on a particular occasion. One thing that these images do tell us, however, is that there was huge variety in the sizes and the make-up of bands; these we have documented in Dance Instrumentation in Britain.

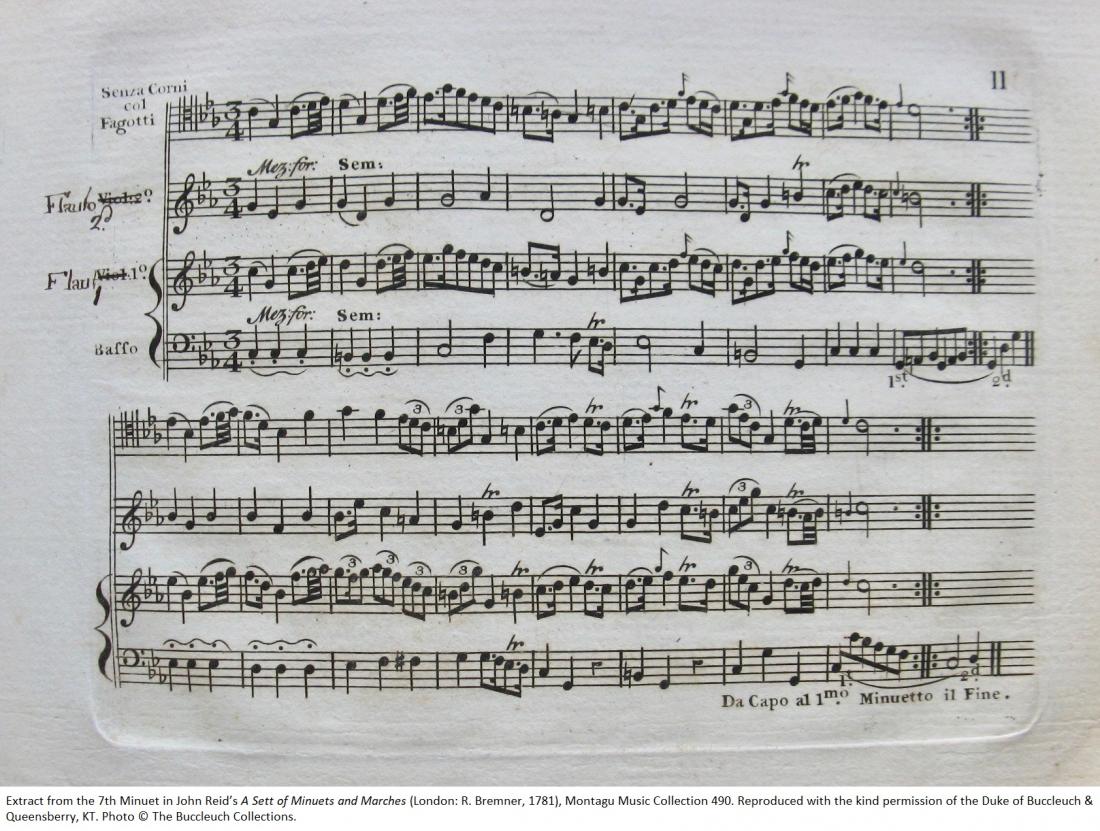

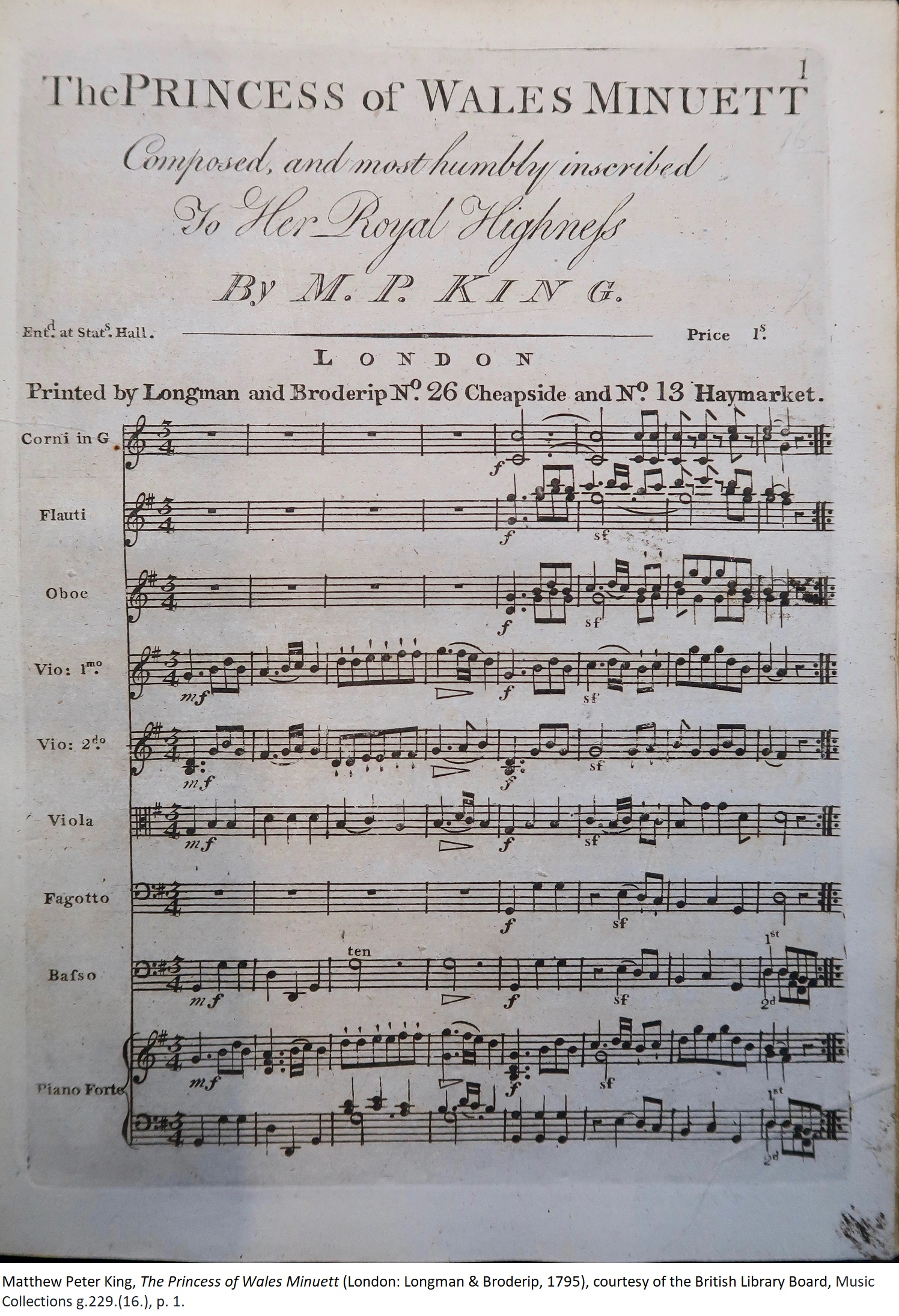

While images might give some ideas on instrumentation they provide nothing on orchestration or execution. For this, we need to turn to the few extant written sources: some dance music exists fully scored such as minuets from Ignatius Sancho’s Minuets Cotillons & Country Dances (c.1767), the 6th Earl of Kelly’s Favourite Minuets Perform’d at the Fête Champêtre (1774), and the minuets from Twelve Country Dances and Three Capricios with Three Minuets composed by the 4th Earl of Abingdon and published in 1787. All of these use similar instrumentation: pairs of violins over a bass with pairs of horns and, in two cases, an extra pair of treble wind instruments as well. This pairing of wind instruments is, of course, familiar from (what we now think of as) concert music of the time. Yet, the symphonies of Carl Friedrich Abel and Johann Christian Bach, for instance, that were written for  and performed at the Bach-Abel Concerts in London between 1765 and 1781, usually used multiple pairs – oboes, bassoons, flutes as well as horns – so these dance scores were comparatively modest. Notable as well is the lack of violas in the middle of the string texture of these dance scores, something that in sinfonias and overtures had not been common since the first half of the century. The Princess of Wales’ Minuett composed and most humbly inscribed to Her Royal Highness by M.P. King in 1795 reflects the larger orchestral size used in many symphonies composed for London in the 1780s and 90s as it adds bassoons to the flutes, oboes and horns, and violas into the string texture.

and performed at the Bach-Abel Concerts in London between 1765 and 1781, usually used multiple pairs – oboes, bassoons, flutes as well as horns – so these dance scores were comparatively modest. Notable as well is the lack of violas in the middle of the string texture of these dance scores, something that in sinfonias and overtures had not been common since the first half of the century. The Princess of Wales’ Minuett composed and most humbly inscribed to Her Royal Highness by M.P. King in 1795 reflects the larger orchestral size used in many symphonies composed for London in the 1780s and 90s as it adds bassoons to the flutes, oboes and horns, and violas into the string texture.

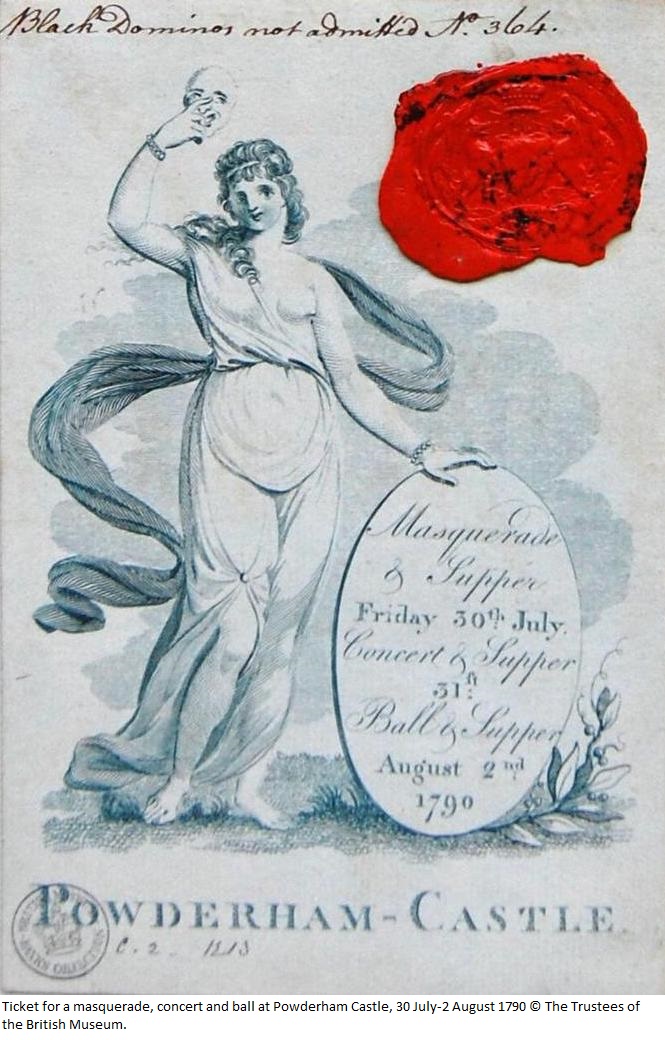

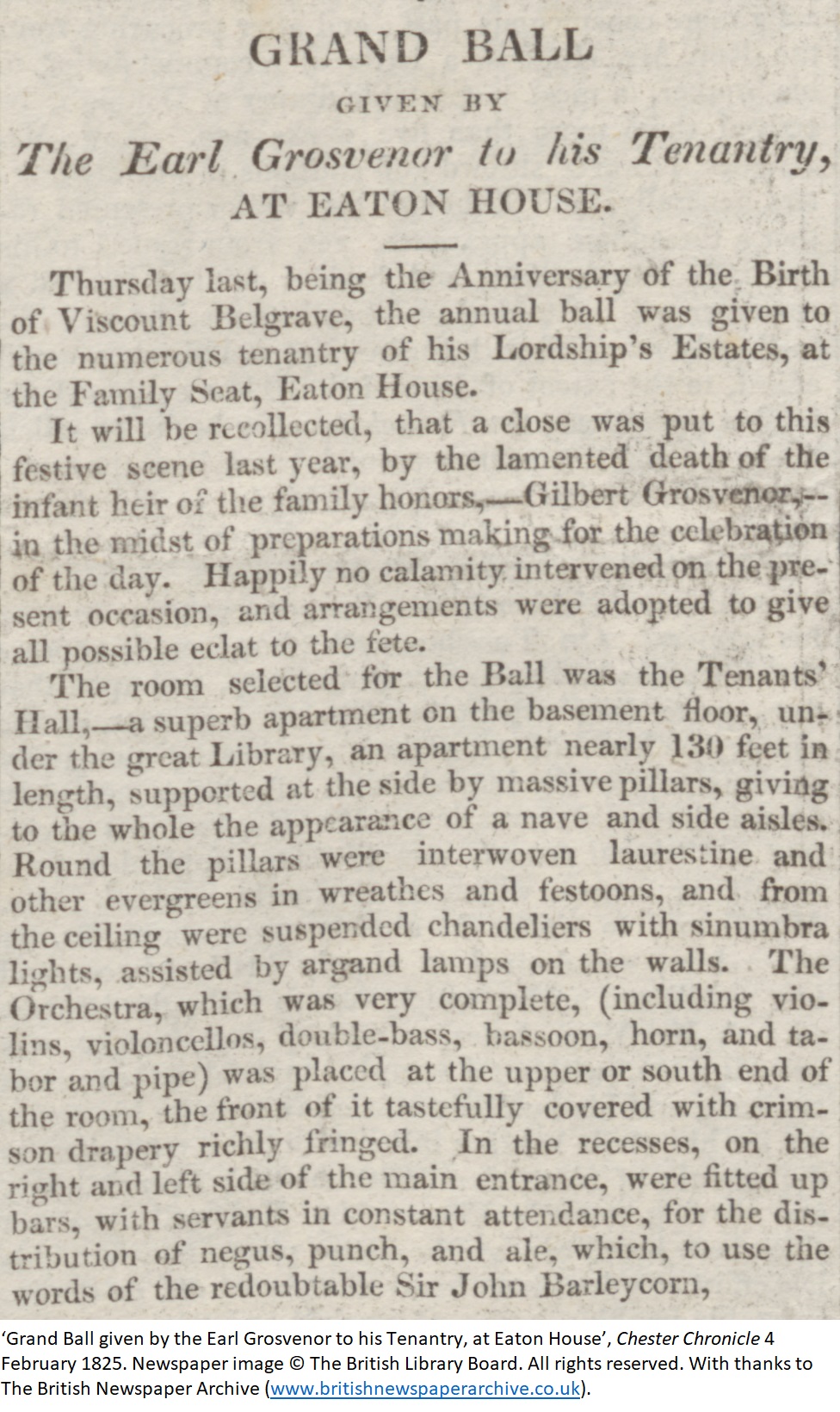

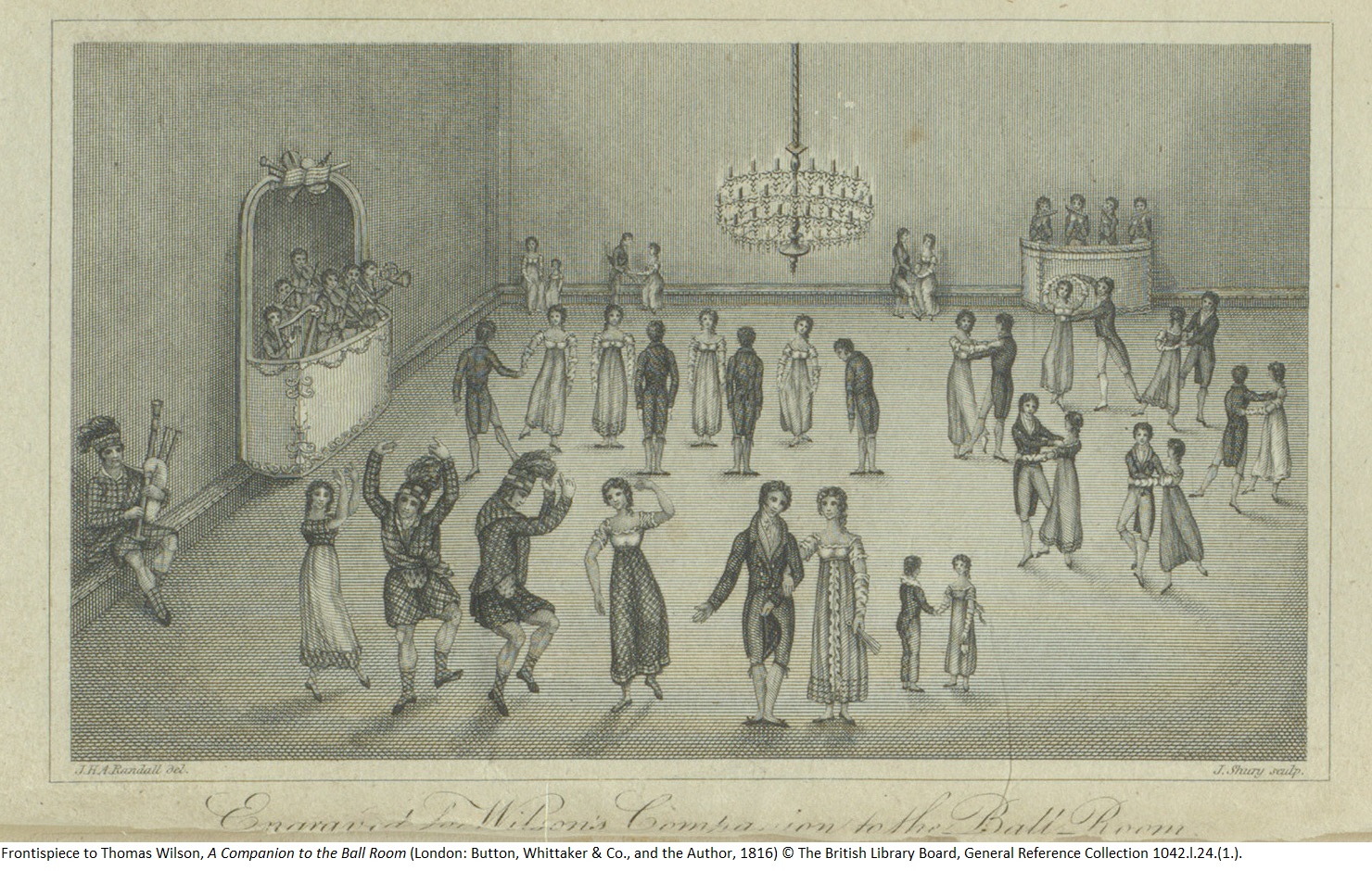

The pairing of instruments in these scores is, however, not always reflected in the depiction of instruments in images of dance bands. The frontispiece to The Rising Sun that heads Dance Instrumentation in Britain is a case in point here. Similarly, Thomas Wilson’s A Companion to the Ballroom, published in 1816, suggests three different groups of musicians as varieties of dance bands: the first consisting of harp, flute, two violins, a wind instrument akin to a clarinet and a horn, the second of four panpipers and the third of a lone bagpiper.  Wilson presents breadth here, ranging from a notional instrumental ensemble to a single musician accompanying dance; while he might be implying particular associations between the bagpiper and the Scotch reel danced near him and the waltz and the panpipes, he also nods to dance in perhaps more intimate spaces rather than in grand ballrooms. While information on the size of bands for grand affairs is sometimes revealed in newspaper announcements or press reports, for domestic dance we rely largely on iconography, on diaries and letters, and on account books that provide lists of paid musicians. Payments to a dancing master – usually a fiddler – or to a single musician hired for dance purposes – often a harper – are frequent. But we also find payments to multiple musicians who attend to play for dance in private houses. At times, these occasions can be rather grand: in August 1790, Lord Courtenay, for instance, pays for Mr Jones, the harper, and seven musicians to stay at Powderham Castle in Devon for a full month to play for balls and other festivities (Devon Heritage Centre 1508M/0/E/Accounts/V/15).

Wilson presents breadth here, ranging from a notional instrumental ensemble to a single musician accompanying dance; while he might be implying particular associations between the bagpiper and the Scotch reel danced near him and the waltz and the panpipes, he also nods to dance in perhaps more intimate spaces rather than in grand ballrooms. While information on the size of bands for grand affairs is sometimes revealed in newspaper announcements or press reports, for domestic dance we rely largely on iconography, on diaries and letters, and on account books that provide lists of paid musicians. Payments to a dancing master – usually a fiddler – or to a single musician hired for dance purposes – often a harper – are frequent. But we also find payments to multiple musicians who attend to play for dance in private houses. At times, these occasions can be rather grand: in August 1790, Lord Courtenay, for instance, pays for Mr Jones, the harper, and seven musicians to stay at Powderham Castle in Devon for a full month to play for balls and other festivities (Devon Heritage Centre 1508M/0/E/Accounts/V/15).

On other occasions, those involved in dancing took it in turns to play for each other as Sophia Baker reports in her diary in December 1800, writing “to tea came the Chapmans, Miss Kirby & Lloyds & Hadsleys a good deal of music &c a Supper after which we danced till ½ past 12 all playing by turns on ye Piano” (West Sussex Record Office Add Mss 7468). Her accounts range from dances accompanied by single instruments – here she mentions the organ (1797), the piano (1803), and the harpsichord as late as 1824! – to those with regimental bands. In the domestic setting, though, dancing to the accompaniment of a single instrument is regularly mentioned and at times was quite informal and spontaneous. In 1798 Mary Jemima Robinson, Baroness Grantham, reports on this practice to Amabel, Countess de Grey, explaining that “a little Piano forte musick, & a Reel, & two or three country dances, in which the Gentlemen were pressed into the service, have helped pass over the evenings” (12 January 1798, Bedfordshire Archives L30/11/240/72). But more modestly sized bands with instrumental combinations that seemed to suggest colour and variety, rather than any model that followed concert music, were also used for subscription balls. On 9 March 1801, a Mr Allen advertises a subscription ball in the London Morning Post with the promise that “the Band, consisting of a Harp, two Violins and a Tambourin or Horn, are the best Musicians that can be had.”

Learning through practice

While the extant scores provided some clear models to follow, the images as well as the collections of dance tunes required some practical interpretational work. In a series of workshops, we reviewed these sources and brought them into dialogue with each other so as to find some starting points for playing late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century dance music today. This practice-based approach allowed us to fill in some gaps based on our own instrumental proficiency, our understanding of historical instruments and, it must be admitted, a good deal of rootedness in modern conventions of playing music composed around 1800. As a historical method this is difficult as we are in danger of affirming conceptions about historical performing practices that we already hold. As such, the exercise had to be highly reflexive to find what the haptic-cum-aural approach can actually tell us. If, therefore, we struggled with the balance within an ensemble of six wind players but only single players on each violin part – something that goes against ensemble habits today – we pondered the options; rather than deciding that the band must have had more violinists we asked, for instance, how we could balance the instruments by adjusting the textures that each contributes to the overall band arrangement. The few full scores that are extant today helped shape our investigation here but we also tried out the smaller and more unusual combinations of harp and violin, or harp, violins and a bass instrument as depicted in Isaac Cruikshank’s 1792 print Rehearsing a Cotilion (sic). Such practice-based research has become a popular method as it yields insights that historical sources cannot provide as long as – informed by ethnographic and social science approaches – one questions and investigates one’s received performing knowledge, habits and conventions (Doğantan-Dack 2015).

Many of the extant images show a fiddler together with a tabor and pipe player, or indeed a tabor and pipe player alone. Our practical work suggested that for domestic settings this combination made a great deal of sense: the tabor presented a strong and steady beat while the pipe’s timbre allowed it to carry the melody audibly and the violinist could switch between doubling the tune and providing a bass line on the lower strings or even filling in harmonies in broken chords or drones. A major caveat in following this performance practice today, though, results from pure pragmatics: in our recording, we made up for the absence of a tabor and pipe player by replicating the timbral combination with the help of a chalumeau and a tambourine, performed by two separate players.

Many of the extant images show a fiddler together with a tabor and pipe player, or indeed a tabor and pipe player alone. Our practical work suggested that for domestic settings this combination made a great deal of sense: the tabor presented a strong and steady beat while the pipe’s timbre allowed it to carry the melody audibly and the violinist could switch between doubling the tune and providing a bass line on the lower strings or even filling in harmonies in broken chords or drones. A major caveat in following this performance practice today, though, results from pure pragmatics: in our recording, we made up for the absence of a tabor and pipe player by replicating the timbral combination with the help of a chalumeau and a tambourine, performed by two separate players.

In rehearsing and recording we played with chord voicings in reaction to the acoustics in different spaces. In our version of James Paine’s 12th set of quadrilles, we introduced various versions of the horn part, replacing the melodic material in “La Tambour” with long held notes, for instance, to add variety and different colours to the dance. Such changes often emerged from a desire for variation within a dance movement that presented the same melodic material for four couples to dance to in sequence. At times, though, it was driven by pragmatics that we share today with our historical predecessors: in Paine’s quadrilles, the natural horn starts playing on a C crook for the first three dances in E minor, C major and G major, but for the fourth dance in D major, “La Caprice de Vauxhall,” a crook change to F is necessary. In live performance, then, the horn player may have to sit out the first A section of the “Caprice” to avoid too large a gap between each of the five dances in the quadrille. And for crook reasons, the horn player is unlikely to have played in the E major section of the first dance, “La Belle Flamand.”

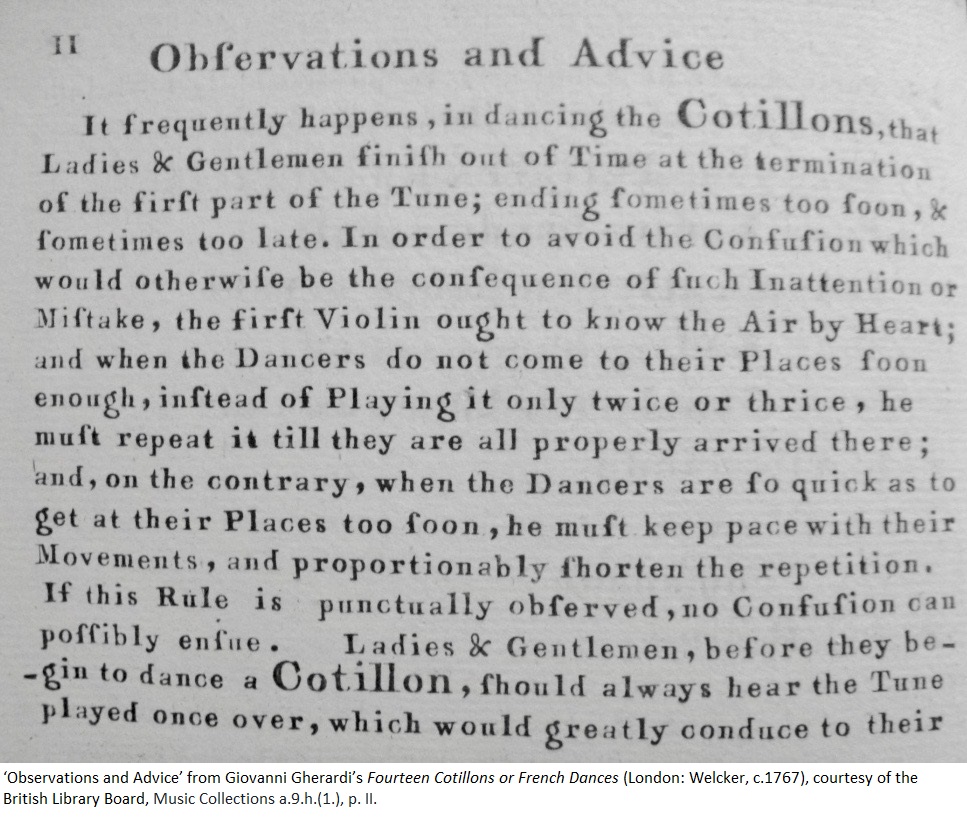

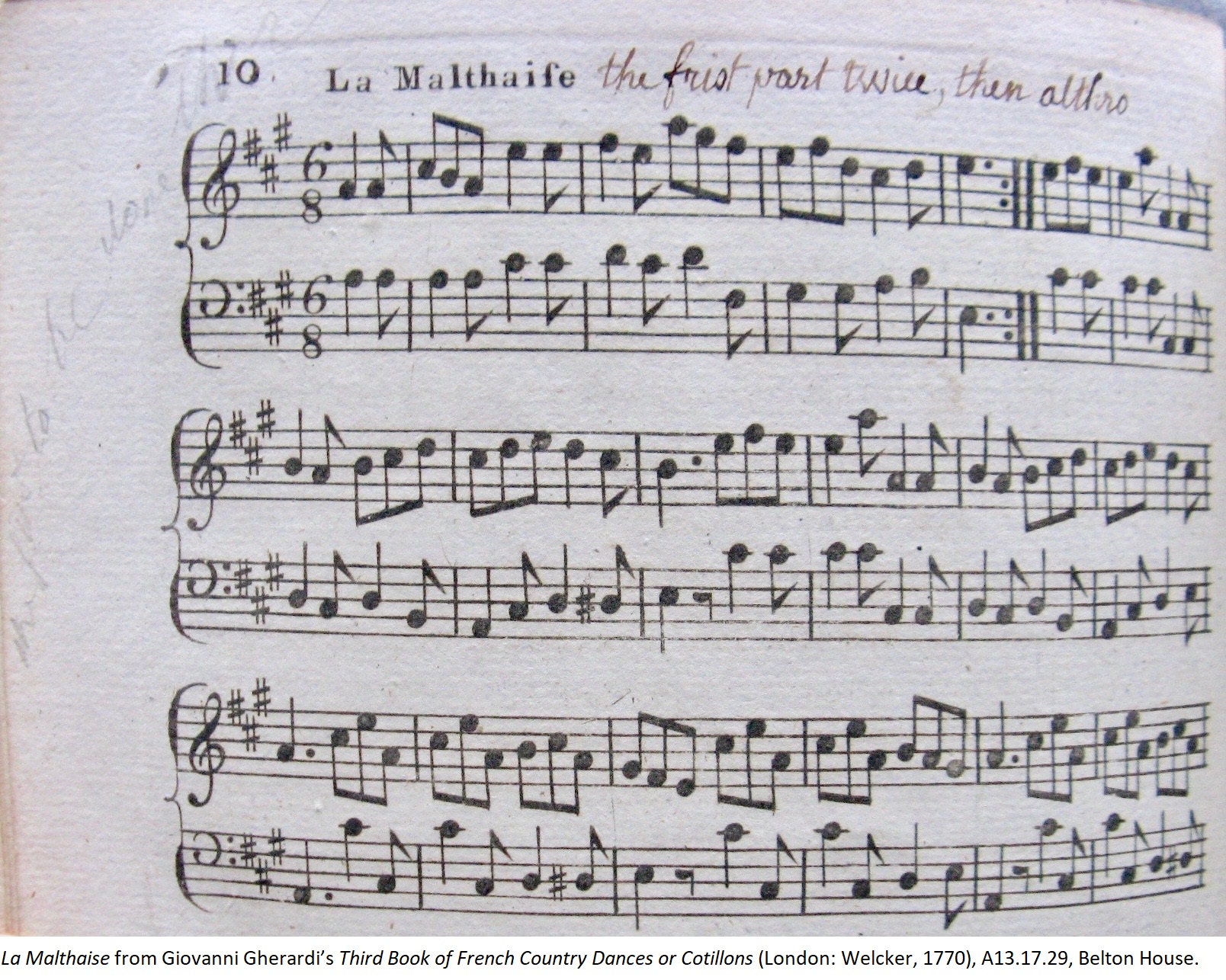

These musical pragmatics cannot be explored in isolation. They rely on a parallel investigation of dance instructions and conventions that have emerged from the study of historic dance. Here, the material evidence requires as much interpretation, though, as the musical evidence does. We therefore workshopped repertoire with dancers and got advice on speeds and on the dances’ characters. Working from keyboard arrangements of quadrilles, by far the easiest way to ascertain how exactly the music fitted with the dance was to have the dancer walk through them while we played. Some knowledge would have been second nature to musicians playing regularly for balls or would, indeed, have been clear simply by watching while playing. The number of repeats needed in quadrilles, for example, is far easier to establish by looking to see when the final couple is taking its turn, than by counting! The repeats in a cotillion depended on the number of “changes” the dancers chose to perform. So, again, visual clues were extremely helpful. Indeed, the French dancing master Giovanni Battista Gherardi explains as much in his first collection of cotillions, the Fourteen Cotillons or French Dances printed by Welcker in London in 1767. Here, he explicitly instructs the first violin to keep watch and play along with the dancers until they have reached the end. Still, it appears that musicians in the 1770s got confused on occasion (just as we did!) for, in his third book of cotillions, someone – perhaps Gherardi himself – annotated a copy of the music by hand at the top of each dance to spell out whether an extra A section was needed.

In his first book of cotillions, Gherardi also explains that a cotillion ought to start with an introductory section that allows the dancers to hear the tune once so as to work out “where the figure of the first Part ends, and where the figure of the second Part begins,” and to “make an obeisance” to each other. The latter, he suggests, is a practice well-known to English dancers from the minuet. Here, the music similarly doesn’t stipulate an extra repeat of the opening A section. Indeed, the ballroom minuet, so the dancers advised us, would string various of the minuets in our printed music together to be of adequate length, following Tomlinson’s advice that the minuet should consist of (at least) six parts of sixteen bars – or eight minuet steps – each (Tomlinson 1735; dancers and dance scholars have advocated flexibility, though, see Thorpe 2003). This presented similar issues for the instrumentation that we encountered in Paine’s quadrilles. The question of whether there was flexibility in the instrumentation when playing three of Ignatius Sancho’s minuets from his Minuets Cotillons & Country Dances one after the other as a long ballroom minuet was answered for us: as the keys change, so the horn crooks needed changing, resulting in variations in instrumentation as the horns sat out the first A section of the next minuet to fix their instruments for the new key. In both, the quadrilles and these long minuets, it seems likely that dance bands would have followed a flexible practice with regards to instrumentation beyond the horn section so as to provide breaks and rests particularly for wind players; playing these dances is a good work-out for all performers, not just the dancers!

![Le Deroute de Jourdan from Ten Country Dances and Four Cotillons with their Basses for the Piano Forte as they are now Danc’d at Bath, for the Year 1797 (Bath: J&W Lintern, [1797]), courtesy of the British Library Board, Music Collections a.222.b.(6.), p. 12. Le Deroute de Jourdan from Ten Country Dances and Four Cotillons with their Basses for the Piano Forte as they are now Danc’d at Bath, for the Year 1797 (Bath: J&W Lintern, [1797]), courtesy of the British Library Board, Music Collections a.222.b.(6.), p. 12.](/sites/sound-heritage.soton.ac.uk/files/fig_6_-_10_country_dances_-_bl_a.222.b6._img_5515_copy.jpg) Given the number of repeats we played in these dances, a gradually more daring addition of ornamentation seemed to happen naturally during our workshops. While the exact nature of these was perhaps not always idiomatic, we agreed that it was highly likely that such practice would have been germane around 1800. Indeed, some printed music includes suggestions of ornamentation. In “Le Deroute de Jordan” in the Ten Country Dances and Four Cotillons… danc’d at Bath (1797), someone at the time notated a possible variation for bars 5 to 8. It is generally accepted that country dances would have included ornamentation or diminutions across the many repeats. At times, the publications of country dances for keyboard rather than melody alone, provide ornamentation examples. But they also tell us something about the status of these scores: the Scottish fiddler and composer Niel Gow, for instance, re-issued his first Collection of Strathspey Reels, originally published in 1784, in 1801 with a title page that suggests “considerable additions and valuable alterations.” The nature of the keyboard part here indicates that the collection was aimed at a genteel market of keyboardists separate from the Scottish fiddle tradition that Gow himself was well versed in; at the same time, it includes suggestions for ornamentations of tunes (albeit in the tradition of keyboard music ornamentation, perhaps, more than folk fiddling). Extempore ornamentation in classical music has, of course, received much scholarship and therefore offered us familiar models in our workshops. While much of the scholarship in this field revolves around solo repertoire some studies have investigated improvisatory ornamentation practices in ensemble music (Spitzer and Zaslaw 1986). So far, we have not found annotations in surviving dance music that might give us a better idea of how such ensemble practice might have worked around 1800. An autograph score of Charles Coote’s Chatsworth Quadrilles of 1843, however, held at the British Library contains variations for the flute and horn parts with the instruction to play these on the second and fourth repeats respectively.

Given the number of repeats we played in these dances, a gradually more daring addition of ornamentation seemed to happen naturally during our workshops. While the exact nature of these was perhaps not always idiomatic, we agreed that it was highly likely that such practice would have been germane around 1800. Indeed, some printed music includes suggestions of ornamentation. In “Le Deroute de Jordan” in the Ten Country Dances and Four Cotillons… danc’d at Bath (1797), someone at the time notated a possible variation for bars 5 to 8. It is generally accepted that country dances would have included ornamentation or diminutions across the many repeats. At times, the publications of country dances for keyboard rather than melody alone, provide ornamentation examples. But they also tell us something about the status of these scores: the Scottish fiddler and composer Niel Gow, for instance, re-issued his first Collection of Strathspey Reels, originally published in 1784, in 1801 with a title page that suggests “considerable additions and valuable alterations.” The nature of the keyboard part here indicates that the collection was aimed at a genteel market of keyboardists separate from the Scottish fiddle tradition that Gow himself was well versed in; at the same time, it includes suggestions for ornamentations of tunes (albeit in the tradition of keyboard music ornamentation, perhaps, more than folk fiddling). Extempore ornamentation in classical music has, of course, received much scholarship and therefore offered us familiar models in our workshops. While much of the scholarship in this field revolves around solo repertoire some studies have investigated improvisatory ornamentation practices in ensemble music (Spitzer and Zaslaw 1986). So far, we have not found annotations in surviving dance music that might give us a better idea of how such ensemble practice might have worked around 1800. An autograph score of Charles Coote’s Chatsworth Quadrilles of 1843, however, held at the British Library contains variations for the flute and horn parts with the instruction to play these on the second and fourth repeats respectively.

The absence of scores and parts for dance music around 1800 raises the larger question whether musicians perhaps played without notated music. Could musicians have performed in multiple parts using only the tune? Dance bands at public balls, particularly after 1800, are regularly depicted with music stands but earlier images usually show musicians packed into small galleries without any obvious space for or device to hold sheet music. In domestic settings, the musicians are often shown to look at the dancers, while much of the imagery of other domestic music making suggests that musicians looked over each other’s shoulders to share one music book (Leppert 1988). Indeed, our workshops suggested that, particularly in the case of country dances and cotillions, musicians could memorise the tunes quickly and could construct at least one accompanying line, either a bass line or a middle line. The possibility of such practice in music-making around 1800 has been explored by others who have pointed out that the music’s reliance on particular harmonic progressions, melodic figurations and a somatic gestural language suggests that musicians shared its vocabulary sufficiently to be able to improvise without the aid of notation (LeGuin 2006; Moseley 2013; McGuiness 2019; Fort 2020). A similar absence of parts exists in the repertoire referred to at the time as “accompanied sonatas,” i.e. sonatas for the keyboard with the accompaniment of the flute or violin and that was aimed particularly at the amateur market at home (Thormählen 2006). It is generally accepted that this repertoire was written with sociable interaction in mind and, whereas the keyboard parts – with title pages stipulating that accompaniment can be added – survive aplenty, the partbooks for the accompaniments are missing in a large number of cases. They may, of course, simply have become separated from the keyboard parts but as the latter make sense in and of themselves without the accompanying part/s, it may be possible that musicians were quite used to doubling lines or providing simple harmonic accompaniments by ear, whether they were professional dance band musicians or amateurs playing in the home.

The absence of scores and parts for dance music around 1800 raises the larger question whether musicians perhaps played without notated music. Could musicians have performed in multiple parts using only the tune? Dance bands at public balls, particularly after 1800, are regularly depicted with music stands but earlier images usually show musicians packed into small galleries without any obvious space for or device to hold sheet music. In domestic settings, the musicians are often shown to look at the dancers, while much of the imagery of other domestic music making suggests that musicians looked over each other’s shoulders to share one music book (Leppert 1988). Indeed, our workshops suggested that, particularly in the case of country dances and cotillions, musicians could memorise the tunes quickly and could construct at least one accompanying line, either a bass line or a middle line. The possibility of such practice in music-making around 1800 has been explored by others who have pointed out that the music’s reliance on particular harmonic progressions, melodic figurations and a somatic gestural language suggests that musicians shared its vocabulary sufficiently to be able to improvise without the aid of notation (LeGuin 2006; Moseley 2013; McGuiness 2019; Fort 2020). A similar absence of parts exists in the repertoire referred to at the time as “accompanied sonatas,” i.e. sonatas for the keyboard with the accompaniment of the flute or violin and that was aimed particularly at the amateur market at home (Thormählen 2006). It is generally accepted that this repertoire was written with sociable interaction in mind and, whereas the keyboard parts – with title pages stipulating that accompaniment can be added – survive aplenty, the partbooks for the accompaniments are missing in a large number of cases. They may, of course, simply have become separated from the keyboard parts but as the latter make sense in and of themselves without the accompanying part/s, it may be possible that musicians were quite used to doubling lines or providing simple harmonic accompaniments by ear, whether they were professional dance band musicians or amateurs playing in the home.

In combining iconography with extant music, the status of the extant music itself is called into question. I have hinted above that the printed music may bear only a tangential relationship to the music that was played for dance as the printed collections were most commonly aimed at those whose pastime it was to play the keyboard or harp. These collections, then, may well have been used to accompany dance on less formal occasions such as those described by Sophia Baker above, but it is less likely that they were used as the basis for performance when a musician was invited to bring his band for a private ball. The question arises with particular urgency in the case of arrangements offered for the harp. These were, in fact, often furnished with a title page designed to broaden the potential audience as is the case with the arrangement of Andrew Roy’s Yorkshire Hussars Quadrilles that we workshopped and recorded. Our practical work – for pragmatic reasons that we share with large parts of the dance-interested population, I assume – included a modern harp. This soon threw up issues around speed, balance and clarity: not only did the repertoire transpire to be highly virtuosic requiring substantial practice but the resonance of the modern harp frequently obscured the semiquaver passages in the melodic material. In adding further instruments such detail was quickly overpowered by those instruments, such as the violin, flute or cello, whose dynamic is not influenced by the rapidity of the notes. As such, we ended up with three questions: are these issues eradicated if using an early Romantic single or double action harp? Did those playing quadrille arrangements at home perhaps not play at quite the tempo![Hand position from Charles Egan’s The Royal Harp Director, being a New and Improved Treatise on the Single, Double, and Triple Movement Harps (London, [1827], courtesy of the British Library Board, Music Collections h.1139, p. 16. Hand position from Charles Egan’s The Royal Harp Director, being a New and Improved Treatise on the Single, Double, and Triple Movement Harps (London, [1827], courtesy of the British Library Board, Music Collections h.1139, p. 16.](/sites/sound-heritage.soton.ac.uk/files/fig_7_-_position_of_the_hand_egan_1827_edited_0.jpg) that the dancers required? And, finally, even if a historic harp resolves the issues, did harps in dance bands perform the role of carrying the melody and bassline all the way through a dance?

that the dancers required? And, finally, even if a historic harp resolves the issues, did harps in dance bands perform the role of carrying the melody and bassline all the way through a dance?

Further work with early Romantic harp specialist Jean Kelly showed that, indeed, the early instrument was far more suited to the semiquaver runs and rapidly repeating notes which were problematic on the modern harp. Jean explained that the issues arise from the much higher tension that modern harp strings are under as well as the greater distance between the harp strings on the modern instrument compared with its earlier counterpart. Both result in a slightly different hand position which then affects the plucking technique. The difference in performing technique and the mechanics of the harp impacted the instrument’s solo repertoire and can indeed be traced through a number of treatises on harp playing published during the nineteenth century. Masumi Kanemitsu-Nagasawa in her recent PhD on the topic goes so far as to suggest that it is more helpful to consider the early Romantic, single-action harp as an entirely different instrument with its own repertoire (Kanemitsu-Nagasawa 2018).

While this means that the extant solo harp arrangements technically may have been a copy of a harp part in a dance ensemble, we were still left to wonder whether the harp would have had such a leading role in the ensemble and what, indeed, the harpist played in the case of all those dances not transmitted in solo arrangements. In other words, what exactly was the relationship between these solo harp arrangements and dance ensemble practices? Mentions of dancing to the harp alone or as part of an ensemble in domestic spaces abound. At times, these appear critical of the notion of dancing to a single harp, suggesting perhaps that a combination of instruments was preferable. In the summer of 1778, for instance, a letter to Thomas Robinson, 2nd Baron Grantham suggests that an assembly at Lady Gower’s was “an odd kind of ball…because there was no musick but a harp, & none but Ladys danced owing to the scarcity & Laziness of the young men” (Bedfordshire Archives L30/14/333/103). Perhaps the arrangements, then, fulfilled a different purpose: the purpose of reminiscing about the grand ball where one first heard the music; the purpose of enjoying the tunes from the opera arranged into quadrilles; and, for the male spectator of the female harpist, perhaps the purpose of imagining the time when he would dance with his object of desire? Indeed, many scores even suggest this single player use in their layout: note on the header image above that the second violin is placed above the first to allow the first violin and bass parts to form a keyboard or harp part which alone can sufficiently capture the music. That at times players wanted to play something resembling the full version more closely might be indicated in the annotations in “Lady Betty Stanley’s Minuet” from The Favourite Minuets perform’d at the Fête Champêtre: here, someone appears to have used the empty first bar in the horns and clarinets to reenvisage the first bar for keyboard or harp alone in a way that combines the first and second violin parts, thereby playing a fuller version of the instrumental score than the bracketed “keyboard or harp part” at the bottom represents.

Many images across our pages here and beyond nonetheless show that the harp regularly formed part of the dance band both in private and in public events. In our workshops and rehearsals we tried therefore to vary the harp part between providing melodic interest and acting as bassline and harmonic filler as we added further wind and brass instruments. While we enjoyed our forays into this improvisatory practice, more work needs to be done in this field and I hope that a harpist out there will pick up the baton. Here, we have provided only a little taste of this: for the Yorkshire Hussars Quadrilles we have provided two separate arrangements, one that replicates an original harp arrangement from 1821 and accounts for the historic harp’s nimbleness, while the other accounts for the resonance of the modern harp. On the recording you can hear Jean Kelly playing the original 1821 arrangement.

I have written elsewhere on these pages about the difficulty of committing something to a recording that resists fixation. Suffice it to say that our practical work combined with our trips down the iconographical lane and the roads to reading scores in a historically appropriate manner led to one overall insight: dance music, perhaps more than concert music, lives on reaction, spontaneity and enjoyment. It requires musicians to react to dancers and their abilities not least in the tempi they choose, to react to the acoustics of the space they play and dance in, as to the particular setting – whether domestic and intimate or domestic and grand or whether, indeed, that of a grand costumed ball – and to the number of dancers involved. This is a live practice and the historical evidence can and should provide first and foremost the inspiration to give this a go!

I would like to thank our dance consultants Mary Collins, Ellis Rogers and particularly Stuart Marsden for their invaluable input in workshops, rehearsals and by email. They were steady companions during our journey of discovery. Stuart spent invaluable time dancing through pieces selected for recordings and his knowledge and love for this repertoire, as well as his generous spirit, infused the music-making we have attempted to capture within them. Any mistakes that occur in the above are entirely mine. I am similarly grateful to Jean Kelly, harpist par excellence and specialist on historic harps, who consulted on the issue of modern and historic harps. Much valuable input arrived along the way from other members of our Sound Heritage network and I would like to thank David McGuiness in particular for many stimulating thoughts and suggestions. I look forward to continuing our collaboration and to extending the dialogue on dance music performing practices to many more musicians, dancers, scholars and all “amateurs and connoisseurs” of late eighteenth-century music.