Dance Types

From the mid-eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century, various dances came into and fell out of fashion. The list below is not exhaustive, but is nonetheless representative of dances found in domestic music collections.

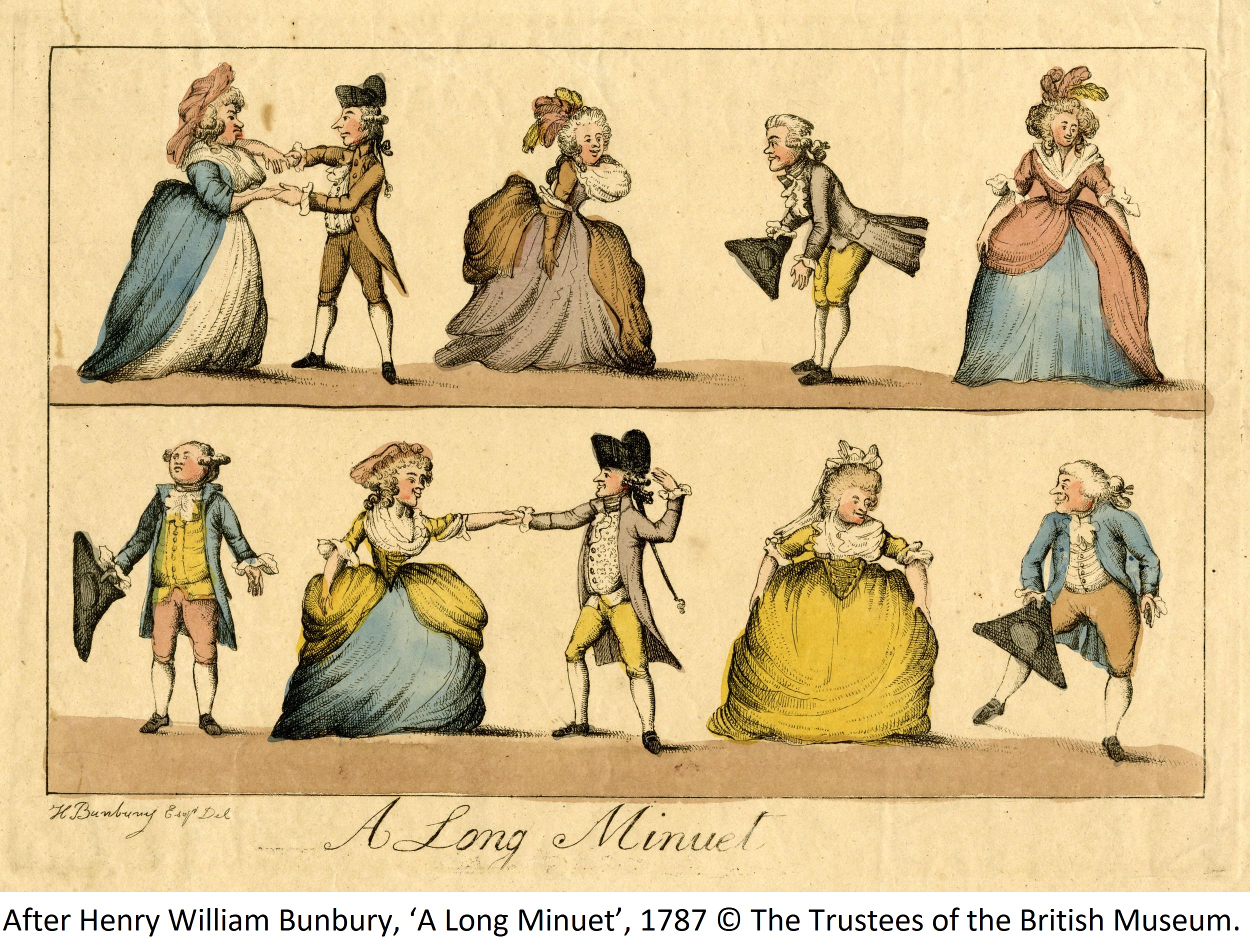

Minuet

Minuet

The minuet was associated with both theatrical and social dance. It was the epitome of early eighteenth century courtly dancing and remained popular among English aristocratic circles into the early nineteenth century. The minuet was a couple dance characterised by an undulating rising and sinking motion that spanned two bars of music in triple time, giving rise to potential cross rhythms. The basic choreography traversed by the couple across the floor was an S or Z shape. Despite its apparent simplicity, the minuet was deceptively difficult and was often the first dance to open a ball. Its performance was cast as the embodiment of elegance and grace, the characterisation of good breeding and gentility.

The minuet de la cour had a specific choreography that originated in the theatre in the late eighteenth century and was performed to a particular piece of music. It quickly transferred to the ballroom and placed heavy demands on the dancers, with one source declaring “there is no medium in this dance, it must be danced with elegance and ease, or not attempted” (Russell and Bourassa 2007, 8). Music for the minuet de la cour can be found in manuscript copybooks and many arrangements were published well into the nineteenth century.

English Country Dance

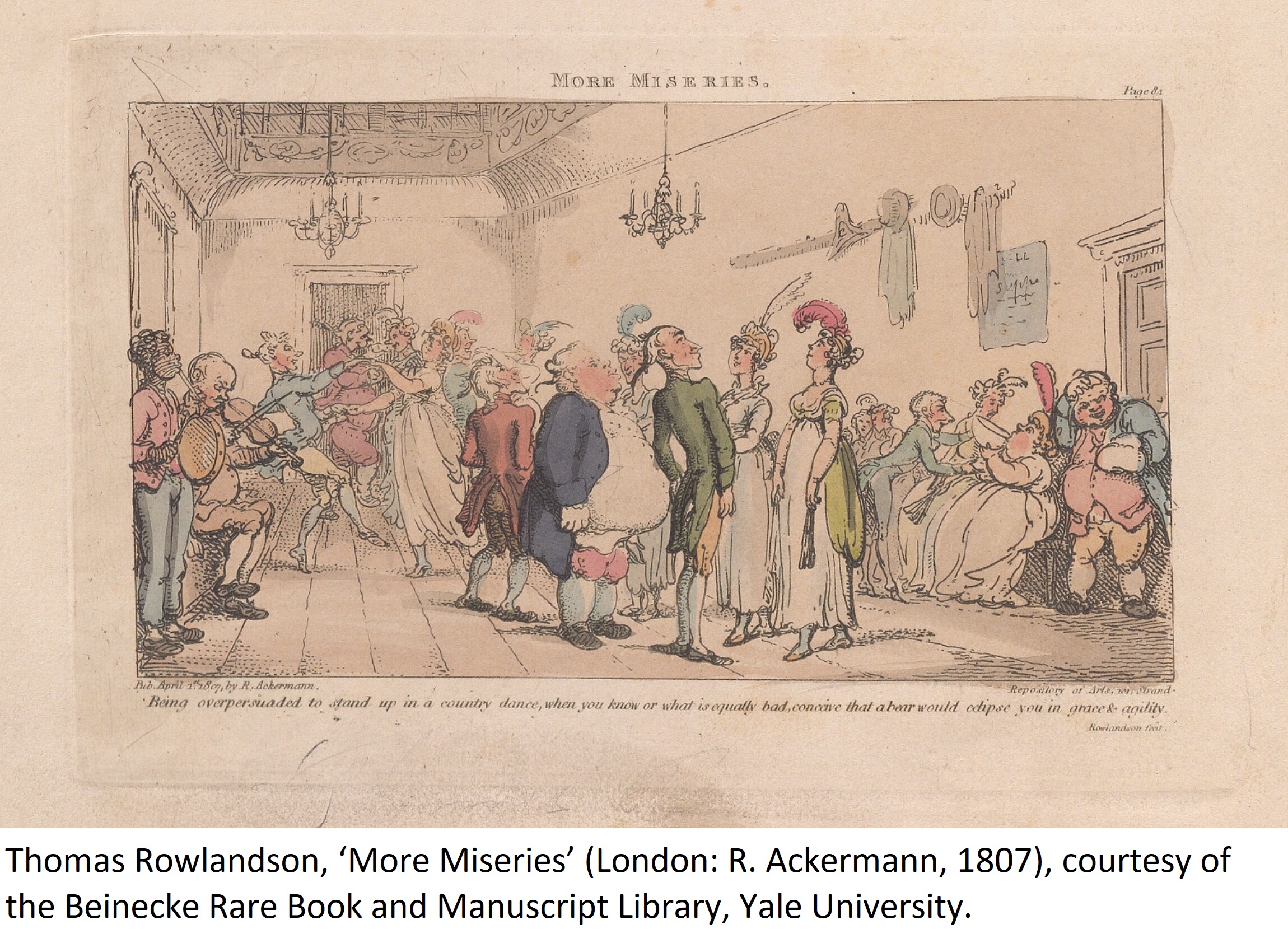

The English country dance was one of the most popular dances in eighteenth-century Britain. During this period the term ‘country dance’ was used generically to describe a formation of dancers in two parallel lines who performed a variety of different figures; in France, the contredanse could also be performed in a square formation, which led to the development of the cotillion. The English country dance consisted of multiple couples who could be subdivided into smaller groups, allowing many people to dance simultaneously. Country dances were often progressive so that couples worked their way from one end of the line to the other. In the early nineteenth century, dancing master Thomas Wilson provided comprehensive analyses of the construction of country dances. Delineating vast numbers of figures, Wilson outlined how they could be combined to create near endless combinations of dances, giving creative agency to dancers to choreograph their own versions. The country dance was also rather porous, in that it could incorporate steps from a range of other dances. The relationship between country dance figures and music was particularly supple: the same combination of figures could be applied to countless country dance melodies, and a single country dance tune could furnish the music for numerous combinations of figures. Music publishers produced annual collections of country dances with brief printed instructions for the figures beneath the score. Understanding the instructions requires some familiarity with eighteenth-century dance vocabulary as a single written phrase encompasses a sequence of movements.

Reel and Strathspey

The reel was one of the most popular dances in the eighteenth century and was believed to have Scottish roots. Three- and four-hand reels, performed by three or four dancers in a line, contrasted setting steps on the spot with a travelling figure, one of the most common being a figure-of-eight pattern. This pattern was also used in country dances, where it was called a reel or hey. Six-hand reels comprised two lines of three dancers and often incorporated figures from country dances. The term ‘reel’ was also used to describe a tune in duple time with an even subdivision of the beat into quavers. Reel tunes could be used for dancing reels, but were also employed for other dances such as country dances. Reels could also be danced to tunes in 6/8 time, sometimes referred to as ‘jig time’.

The strathspey was performed to a slower reel tune, allowing for more intricate steps, that came to be characterised by the use of dotted rhythms, including the ‘Scotch snap’. However, in the late eighteenth century the musical differentiation between reels and strathspeys was less distinct, as the same name could be applied to tunes with different musical characteristics. Many country dances include ‘reel’ and ‘strathspey’ in their titles, thus indicating musical traits rather than denoting particular dance steps. Musicians and dance teachers travelled freely across the English-Scottish border, so English country dances went north and many Scottish tunes and dances migrated south. Susan Sibbald recalled learning “Scotch steps” while at school in Bath, which she put to good use during her social debut at a Caledonian Ball in London (Hett 1926, 37).

![George Cruikshank, ‘The Sailors Hornpipe The Dancing Lesson Pt 4’ (London: Thomas McLean, [1835?]), reissue of a print from 1825, courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. George Cruikshank, ‘The Sailors Hornpipe The Dancing Lesson Pt 4’ (London: Thomas McLean, [1835?]), reissue of a print from 1825, courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.](/sites/sound-heritage.soton.ac.uk/files/filefield_paths/george_cruikshank_the_dancing_lesson_pt_4_1835_reissue_of_1825_lewis_walpole_library_0.jpg) Hornpipe

Hornpipe

The hornpipe was a step dance which articulated rhythmic impulses through the feet, aided on some occasions by clogs. It was known in both solo and group forms, and was danced in social and theatrical settings. Before the eighteenth century, hornpipes were danced in triple meter, often in 3/2 time, incorporating syncopated rhythms. By the middle of the century hornpipes appeared in 2/4 or 4/4 time, characterised by runs of quavers with an emphasis on the second and third beats of the bar. Although hornpipes had at times been considered vulgar, hornpipe music was used in late seventeenth-century country dances (sometimes called maggots, delights or whims) and hornpipe stepping was incorporated in country dances into the eighteenth century. In England, group hornpipes were performed in a row but each dancer had their own steps to exhibit. This display element was seen in the theatre where hornpipes were incorporated into stage productions and a number of hornpipe tunes were named after theatrical dancers. The dancing master Giovanni Gallini reported that “foreign comic dancers, on their coming here, apply themselves with great attention to the true study of the hornpipe, and by constant practice acquire the ability of performing it with success in foreign countries, where it always meets with the highest applause” (Gallini 1762, 183). By 1760 the hornpipe was also clearly associated with sailors (‘Jacky Tars’) and in the nineteenth century learning the hornpipe was incorporated into naval education.

Cotillion

The cotillion was a French dance for four couples arranged in a square formation. It extended the French contredanse by interspersing a series of alternating formations called ‘changes’ with the main figure. The changes were standard formations, such as dancing in a circle, turning your partners or creating a star pattern. They ranged from approximately nine to fourteen in number and were used in all cotillions to intersperse the figure which was specific to one cotillion. As the dance progressed, the dancers would move through the changes by performing one change, then the main figure, then the next change, and again the main figure. In this sense the cotillion functioned like a rondo or verse and chorus. The figure was more intricate than the changes and as this was specific to a given cotillion it essentially formed the core and the character of the dance. As the changes remained more or less the same over time, only the latest figures would have needed to be learned for each season. The cotillion was known in England from at least the mid 1760s and the publication of a number of collections of cotillions towards the end of that decade attests to its popularity. Newspapers advertised cotillion balls and sometimes dedicated spaces within a fashionable establishment were set aside for cotillion dancing. The popularity of the cotillion had declined by the nineteenth century and was overtaken by the quadrille, but Jane Austen still expressed her preference for them in 1817, declaring to her niece, “Much obliged for the Quadrilles, which I am grown to think pretty enough, though of course they are very inferior to the Cotillions of my own day” (Le Faye 2011, 345).

The cotillion was a French dance for four couples arranged in a square formation. It extended the French contredanse by interspersing a series of alternating formations called ‘changes’ with the main figure. The changes were standard formations, such as dancing in a circle, turning your partners or creating a star pattern. They ranged from approximately nine to fourteen in number and were used in all cotillions to intersperse the figure which was specific to one cotillion. As the dance progressed, the dancers would move through the changes by performing one change, then the main figure, then the next change, and again the main figure. In this sense the cotillion functioned like a rondo or verse and chorus. The figure was more intricate than the changes and as this was specific to a given cotillion it essentially formed the core and the character of the dance. As the changes remained more or less the same over time, only the latest figures would have needed to be learned for each season. The cotillion was known in England from at least the mid 1760s and the publication of a number of collections of cotillions towards the end of that decade attests to its popularity. Newspapers advertised cotillion balls and sometimes dedicated spaces within a fashionable establishment were set aside for cotillion dancing. The popularity of the cotillion had declined by the nineteenth century and was overtaken by the quadrille, but Jane Austen still expressed her preference for them in 1817, declaring to her niece, “Much obliged for the Quadrilles, which I am grown to think pretty enough, though of course they are very inferior to the Cotillions of my own day” (Le Faye 2011, 345).

Allemande

Allemande

The term ‘allemande’ was applied to several different dances across time. In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries it was known as a moderate processional dance in duple meter. By the time the allemande appeared in Baroque dance suites a century later, it seems to have existed only in instrumental form and not as a dance. By the mid-eighteenth century a turning couple dance in triple time, which was described variously as containing leaps and employing fast changes in arm position, was known as Deutsche in German-speaking regions and as allemande outside of those areas. When it migrated to Paris, the emphasis lay on the intricacies of the hand and arm positions and it was nearly always danced in duple time. Giovanni Battista Gherardi’s Twelve New Allemandes and Twelve New Minuets includes allemandes in both 3/8 and 2/4 time; in the preface, he also mentioned “the Trotting and Leaping kinds” of allemandes (Gherardi [1769], 2). The turning nature of the dance and the holding positions of the couples both prefigured the waltz.

‘Allemande’ was also used to describe a figure that was incorporated into other dances, such as the country dance, cotillion and quadrille. In cotillions it was utilised both within the changes and the main figure, while some dances were specifically designated as allemande cotillions. A variety of descriptions of the allemande figure exist in historical sources, pointing to diversity in the way it was understood and performed; Thomas Wilson was clear in distinguishing between allemandes within country dances and quadrilles. In his A New Collection of Forty-Four Cotillons, Giovanni Gallini described the allemande figure as being “performed by interlacing your Arms with your Partner’s, in various ways” (Gallini [c.1770], 5). It is this interweaving of arms which forms the common ground between the different allemande figures and which relates back to the allemande as a dance itself.

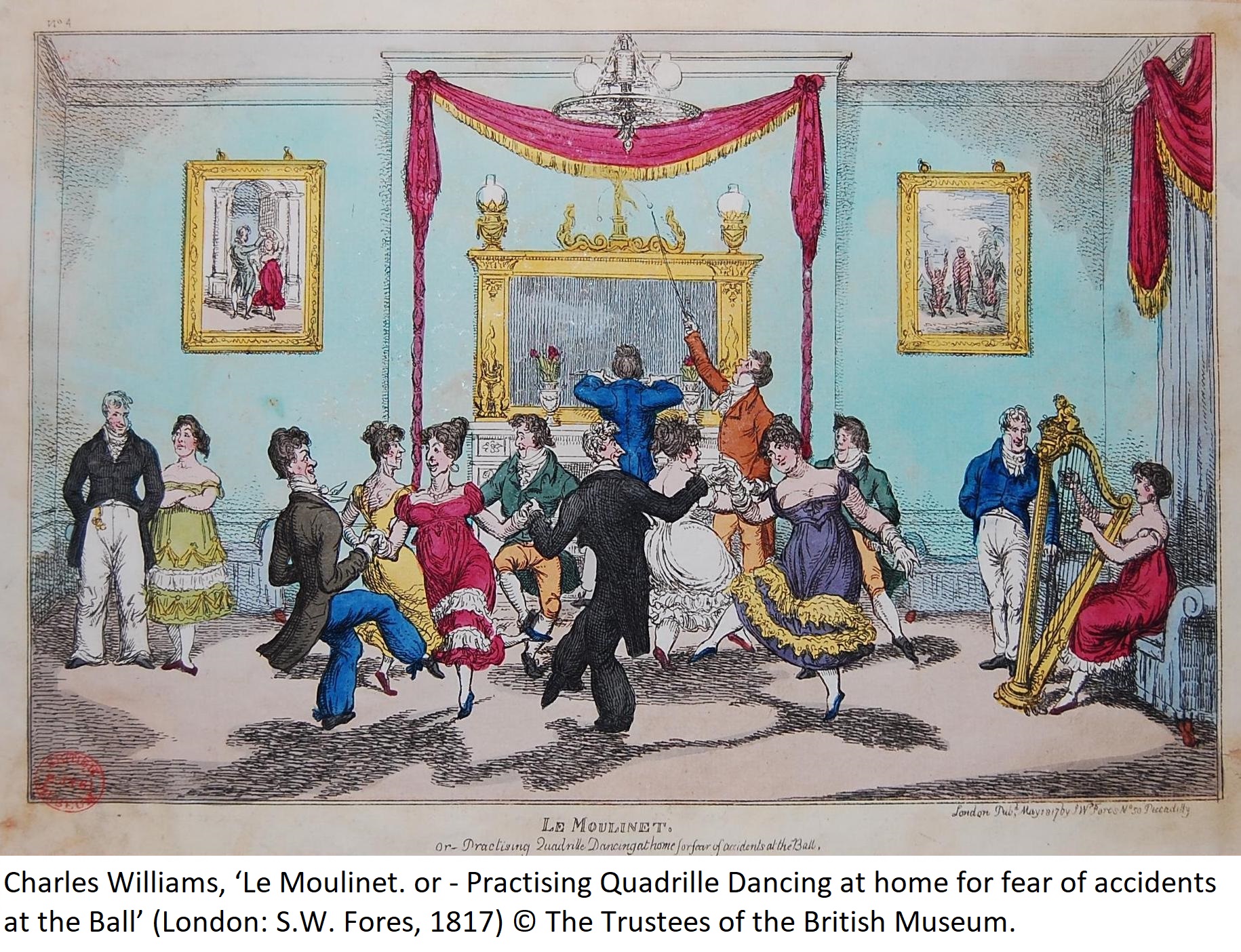

Quadrille

The quadrille was one of the most prominent dances in the nineteenth-century ballroom. It was known in England early on in the century as it was introduced at the fashionable Almack’s Assembly Rooms in London by around 1815. Its genesis lay in the cotillion: as the number of changes were reduced and eventually eliminated in the late eighteenth century, cotillion figures were connected together to form the quadrille. The arrangement of couples in a square formation was retained. Quadrilles were commonly performed in groups called ‘sets’, which usually comprised five or six quadrilles danced one after the other. The most popular combination was the “First Set” which contained the figures La Pantalon, l’Eté, La Poule, La Trenis and/or La Pastourelle and a Finale.  Each of these figures are associated with specific sequences of steps which would have been taught in dance lessons.

Each of these figures are associated with specific sequences of steps which would have been taught in dance lessons.

The figures were indicated via instructions at the bottom of the music score or, when they became well known, simply by the names of the figures themselves, such as La Pantalon. Some scores provided different figures set to the same length of music, so that the First Set could be danced as an alternative option; other sets of quadrilles required music of a different length. Each quadrille in a set was repeated multiple times so as to allow each couple to perform the figures in turn. As this was clear to the musicians, the number of repetitions was not usually indicated on the score as the repeat structure was implicit in the figures, and musicians could, of course, usually see the dancers and therefore watch the couples’ progress through the music. The quadrille had no explicit defining musical features beyond the need to maintain a certain compositional length, appropriate meter and constancy of tempo, so music could be (and was) adapted from a wide variety of sources: extracts from operas (including arias) and ballets regularly formed the basis for quadrille music, as did popular tunes, national airs and on occasion sacred music. Such pilfering not only increased the spread and context in which such music was heard, it also meant that music without any original connection to dance could in turn be understood as dance.

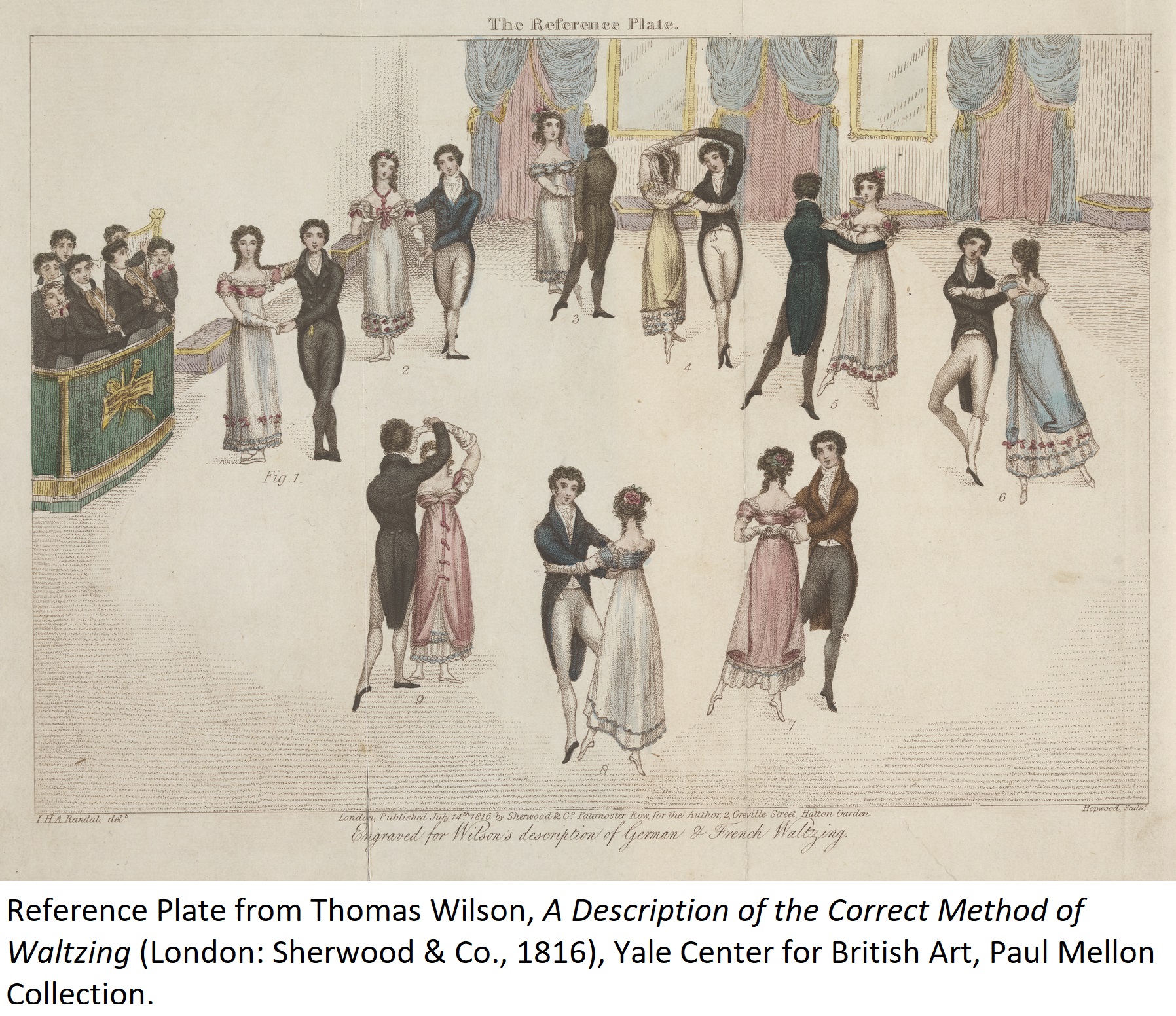

Waltz

The waltz was one of the most provocative and yet enduring dances of the nineteenth century. A revolving couple dance in triple time, it was the focus of a gendered moral discourse that sprang up on account of the physical proximity it encouraged and concerns about its adverse effects on (female) health. The waltz was danced at Almack’s Assembly Rooms around 1812 and in 1816 it appeared to receive royal sanction, as it was performed at a ball hosted by the Prince Regent at Carlton House. However, The Times launched a crushing attack on 16 July as a consequence, objecting vociferously to the dance on behalf of English female modesty:

“We remarked with pain that the indecent foreign dance called the Waltz was introduced (we believe, for the first time) at the English Court on Friday last. This is a circumstance which ought not to be passed over in silence. National morals depend on national habits: and it is quite sufficient to cast one’s eyes on the voluptuous intertwining of the limbs, and close compressure of the bodies, in this dance, to see that it is far indeed removed from the modest reserve which has hitherto been considered distinctive of English females. So long as this obscene display was confined to prostitutes and adultresses, we did not think it deserving of notice: but now that it is attempted to be forced on the respectable classes of society by the evil example of their superiors, we feel it a duty to warn every parent against exposing his daughter to so fatal a contagion”.

The same year, Thomas Wilson published A Description of the Correct Method of Waltzing, in which he carefully distanced waltzing from disreputable implications, emphasising the dance as “a spectacle of graceful beauty” (Wilson 1816, 52). Despite the outrage, the waltz became firmly established in England and by 1829 G. Yates complained that “the fashionable scamper that has now usurped the name…is nothing in short but an outright romp” (Yates 1829, 55). Queen Victoria mentioned often in her journals how waltzes and galops alternated with quadrilles during balls, although she was obliged to sit them out until after her marriage. On 24 February 1840 she noted, “I danced several Quadrilles & Valses & a Gallop with dearest Albert, who is a splendid dancer” before concluding with her usual enthusiasm “I never enjoyed myself more”.

Galop

The galop (or galopade) was one of the simplest nineteenth-century couple dances. It arrived in London in the late 1820s and found its way into operas, ballets and balls. It consisted principally of couples employing chassés – a step-together-step gliding motion – to “gallop-hard” across the ballroom at a quick pace (Bristol Mercury 24 December 1836). The galop was often used as a concluding dance in balls and was also incorporated into quadrilles. John Robert Seaton advised dancers to “assume a sprightly attitude” and recommended no more than sixteen dancers as a greater number was “apt to occasion confusion” (Seaton 1848, 54). In The Great Metropolis, James Grant satirically captured the energy and enthusiasm of galloping dancers, describing how “some of the more spirited of the dancers, especially among the male sex, often dash against the ropes in the midst of the gallopade, and sometimes, by the rebound, are thrown prostrate on the floor…it not unfrequently happens that they prove a stumbling-block to some “charming young lady,” who, before she is aware, falls over them, and is stretched in the same horizontal posture as themselves” (Grant 1837, 35). Galop music could be drawn from vocal repertoire, including opera, and sometimes included special effects like pistol shots.

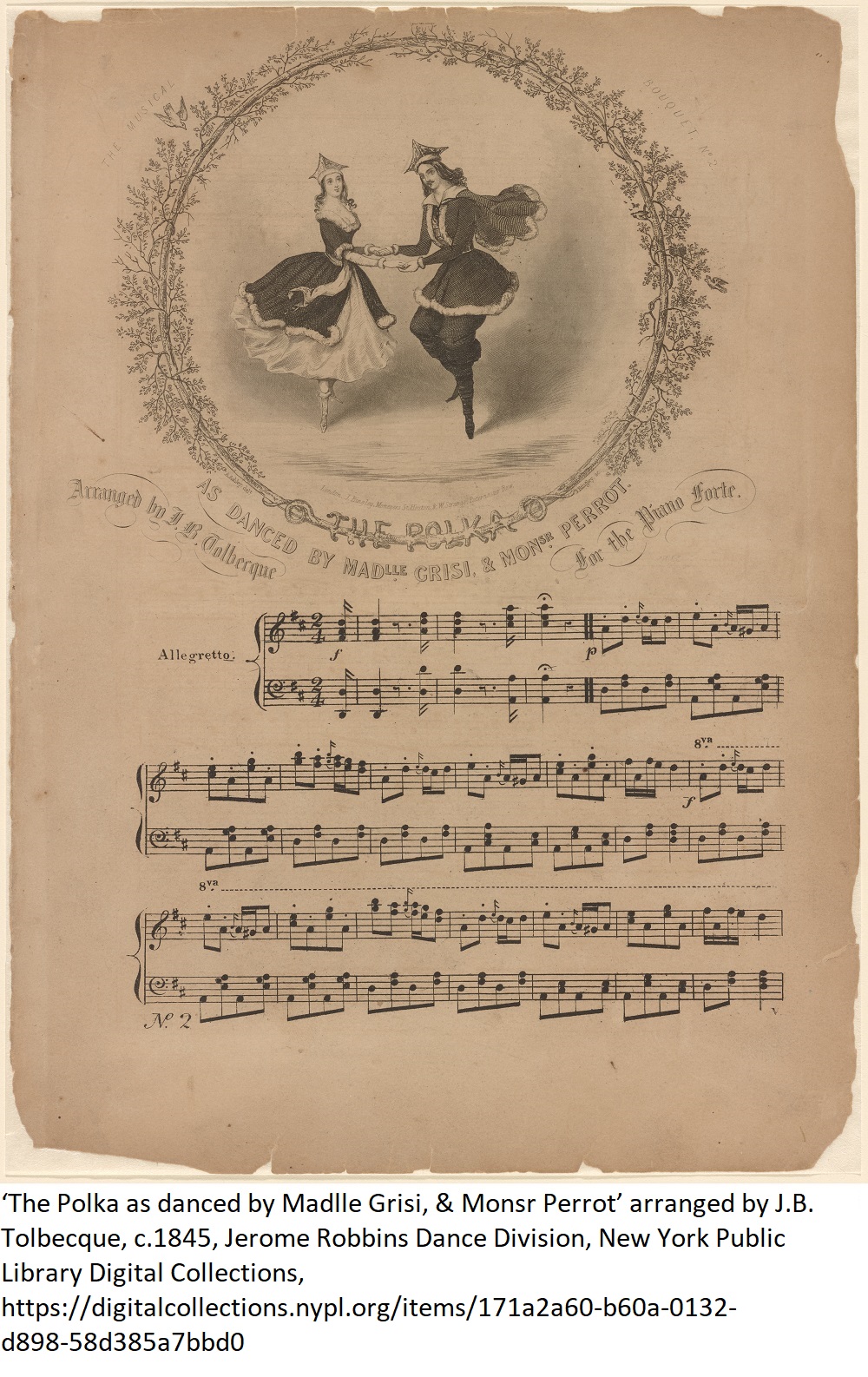

Polka

Polka

The polka was a jaunty couple dance with origins in the waltz, galop and Scottish strathspey. Originally consisting of five figures in sequence, it was soon reduced to a rotating movement. In this it mirrored the waltz and it incorporated the sliding step of the galop in combination with a skipping motion, although it was performed at a more moderate pace than the galop. The polka burst onto the London scene in 1844 via French dancing masters and theatrical performances, and set off a veritable polka craze, prompting considerable media coverage and the sale of merchandise. As John Bull reported not long after its introduction:

“It is only a few weeks since the Polka was heard of, for the first time, in London, as a novelty which had suddenly turned the heads, as well as the heels, of the whole Parisian population...Already it is nightly exhibited at all our theatres, from the Opera-house to the smallest of the minors; the newspapers teem with advertisements from teachers of dancing, announcing that they teach the Polka in true Parisian style, and by-and-by, in every soirée dansante, from Almack’s to the slightest carpet-dance to the pianoforte, there will be nothing but the Polka” (1 June 1844).

As with other dances, the polka step was adapted to form hybrid genres, such as the polka-quadrille and polka-mazurka. Musically, the polka used characteristic combinations of quavers and semiquavers to drive the movement forwards.