Dance as Social Activity

“Never was so riotous a day as yesterday, Cottillions [sic] morning, noon & night, & after that singing & drinking Champagne till 4 o’Clock in the morning. Some of the men in bed all day to-day but enough sober’d to make out a Cottillion to-night”

Nelly Mundy, sister to Lady Hester Newdigate, wrote this enthusiastic observation while the two were visiting Buxton together in 1781 to see if the spa town’s waters would help Lady Newdigate’s ailments (Newdigate-Newdegate 1898, 26). It highlights the significance of social dance as a lively part of entertainment in the Georgian era and shows music-making’s crucial role in light-hearted merry-making. Beneath the surface, though, dance was also put to use strategically in many social endeavours.

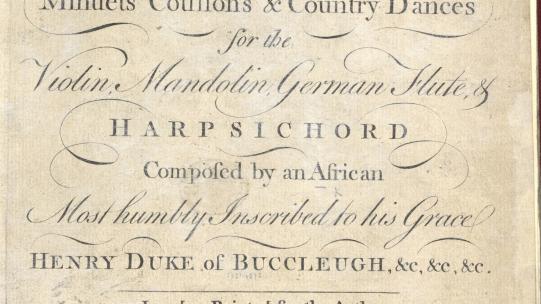

Behind the skill of dancing a cotillion was an education in how to move and how to behave, as well as an understanding of steps and figures. The use of rules in assembly rooms codified group behaviour and in some cases placed clear limits on who was accepted and who was not (Girouard 1990). Some found these rules irksome – in 1816 Anne Lister hardly found it worthwhile to go through “the fuss of dressing at 9, to break up, accordg to rule, precisely as ye clock strikes 11” in Buxton amidst dwindling numbers of subscribers. The regulated activity exerted by assemblies found its parallel in the controlled circulation of promenaders in London’s iconic pleasure gardens (Borsay 2013). Dance itself as a form of behavioural control extended into the industrial environment and was at its most extreme on slave ships, where slaves were forced to dance for their own health and the entertainment of others (Emery 1972).

Behind the skill of dancing a cotillion was an education in how to move and how to behave, as well as an understanding of steps and figures. The use of rules in assembly rooms codified group behaviour and in some cases placed clear limits on who was accepted and who was not (Girouard 1990). Some found these rules irksome – in 1816 Anne Lister hardly found it worthwhile to go through “the fuss of dressing at 9, to break up, accordg to rule, precisely as ye clock strikes 11” in Buxton amidst dwindling numbers of subscribers. The regulated activity exerted by assemblies found its parallel in the controlled circulation of promenaders in London’s iconic pleasure gardens (Borsay 2013). Dance itself as a form of behavioural control extended into the industrial environment and was at its most extreme on slave ships, where slaves were forced to dance for their own health and the entertainment of others (Emery 1972).

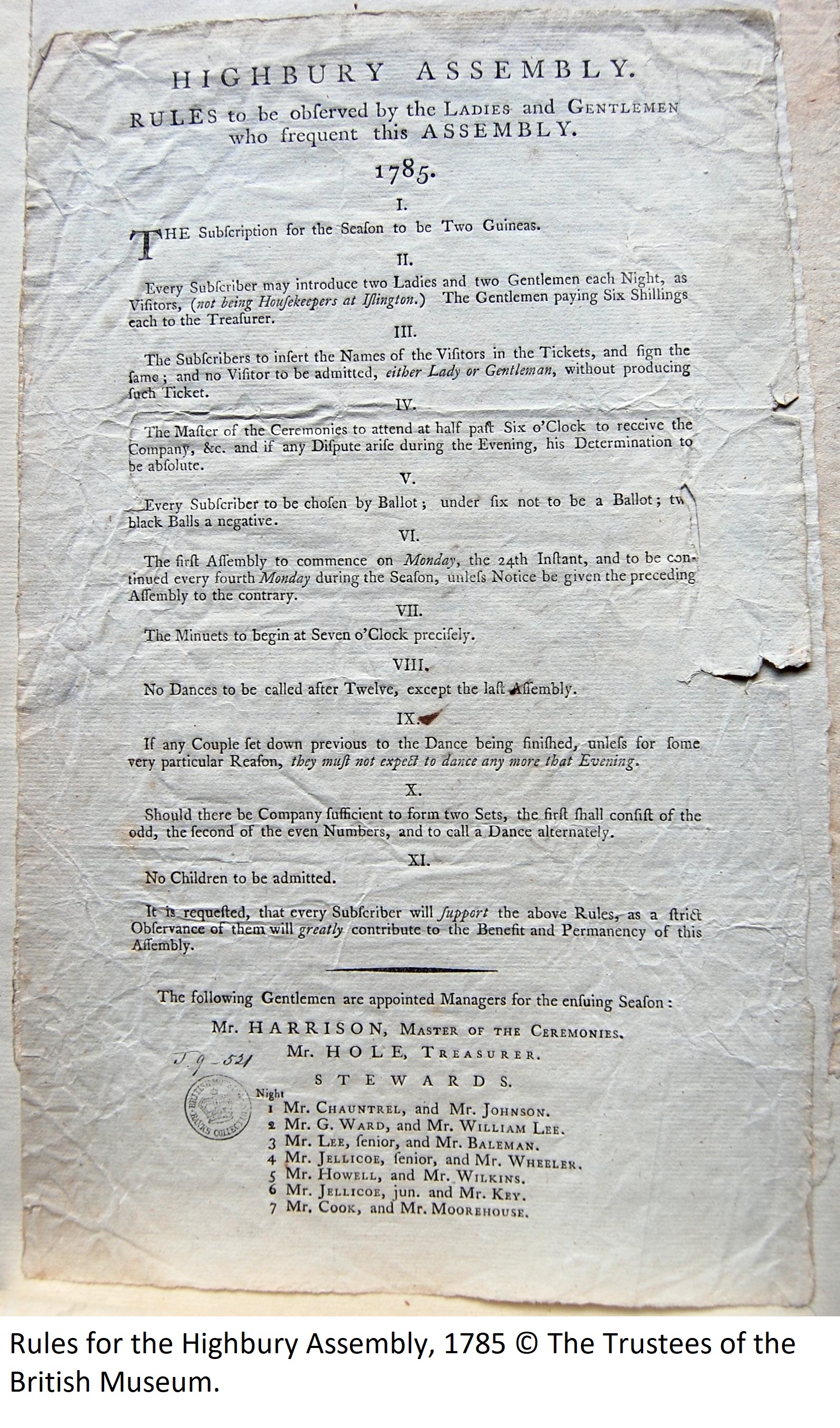

Balls and assemblies provided the scaffolding for the interplay of consumption, patronage and power. Dances held on country estates showcased fine architecture and stunning interior design whilst often also celebrating patriarchal lineage and highlighting class distinctions. Resplendent costume balls held by Queen Victoria in the mid-nineteenth century ostentatiously lent support to Britain’s struggling manufacturers by insinuating connections between the wellbeing of the working classes and the continued consumption of luxury by the elite, whilst also strategically staging the monarchy’s strength and glory (Munich 1996). Election balls sought to win votes for candidates, while political agency could be deployed in theatrically conceived spectacles that were not overtly political. The focus on bodily display meant that the acquisition of skill was commercialised; the transactional power of such skill was put to use in venues like Almack’s Assembly Rooms which facilitated marriages (Rendell 2002).

Beyond these broad social narratives, dance was also an important part of family and community life. Sophia Baker, daughter of William Baker MP of Bayfordbury in Hertfordshire, wrote in her diary in January 1798 that several visitors “came to see us dance & we made up Country Dances afterwards” while in September a Miss Burton dined with the family and “danced in the evening to the P. Forte with us at a great rate” (West Sussex Record Office Add Mss 7466). The Harris family in Salisbury attended local assemblies but also included dance in their own theatrical productions, in addition to writing and sharing dance music (Burrows and Dunhill 2002). The day after attending a masquerade in Hampshire, the composer John Marsh played through cotillion tunes on a fiddle to the Trenoweth family “as well as I co’d recollect them” as part of remembering the event (Robins 1998, 68). In a more lasting tribute, family members and acquaintances could be written into dance itself through individual dance titles and dedications.

![James Caldwall and Charles Grignion after Robert Adam, ‘Inside view of the Supper-room & part of the Ball-room in a Pavilion erected for a Fête Champêtre in the Garden of the Earl of Derby at the Oaks in Surry [sic], the 9th of June, 1774’, 1780 © The Trustees of the British Museum. James Caldwall and Charles Grignion after Robert Adam, ‘Inside view of the Supper-room & part of the Ball-room in a Pavilion erected for a Fête Champêtre in the Garden of the Earl of Derby at the Oaks in Surry [sic], the 9th of June, 1774’, 1780 © The Trustees of the British Museum.](https://sound-heritage.ac.uk/sites/sound-heritage.soton.ac.uk/files/styles/page_reference_crop/public/james_caldwall_charles_grignion_-_inside_view_of_the_supper_room_the_oaks_1780_british_museum_-_main_image.wc_.jpg?itok=G2a09EDX)