Dance Music Recordings

In many ways, recording dance music goes against the grain of all that this music is about. Whether it’s a minuet or a cotillion or a quadrille, when playing for dancers you react to visual clues: how many more repeats are needed? Are the tempo, energy level and volume right for the dancers? Where do the dancers need to be carried through and where might there be moments to breathe in the music without inadvertently leaving the dancers frozen in mid-air? And when playing for live dancing you want to have as much fun as the dancers, so what do you do? You might start to ornament your tunes, or to vary the instrumentation and texture on the spot; if it all gets too much surely one of the dancers will shoot you a glance to suggest that you are getting in the way? You have no fear of wrong notes in your extemporisation because no-one listens that closely! So, playing dance music provides a great deal of freedom and room for experimentation. In the process you discover the great flexibility in the musical language of dance music around 1800 – a flexibility you might even transfer to more fully composed music of the time. Fixing this music on a recording takes away that freedom as you have to make decisions on the sequence in which you place “takes” with ornaments; you start to plan whether the second and third couple in your quadrille might be accompanied by winds alone while the first and fourth dance their turn to the sounds of the full band; and you present in uninterrupted sequence what was unlikely in live performance due to the need for crook changes in the horns or pure exhaustion on the part of your piper.

The recordings we have produced here are an attempt to capture as little planning and as much spontaneity as possible. We did not spend hours putting down multiple “takes” of each piece, section or phrase as is common practice in commercial recordings today, but we hope to have captured the verve of the different dances. The recordings were envisaged as a final meeting of a series of workshops with students at the Royal College of Music, many of whom study the field of Historical Performance. In the end, hit by a global pandemic, the recordings had to be postponed by 15 months and the cross-over of students participating in the workshops and those participating in the recordings was somewhat reduced. We are grateful for the spirit that each one of them brought to this project nonetheless.

At the heart of our recording work are the fabulous arrangements produced by Robert Percival. Robert brought to the process his long years as a professional classical bassoonist, his intimate knowledge of the workings of classical instruments and his extensive experience in arranging music from around 1800 on the model of the many, many arrangements that circulated at the time and that ranged from symphonies for string quartet to operas for the popular eighteenth-century Harmoniemusik. His approach was informed by his respect for any original material that we had to hand: at times, a full score that needed little beyond transcription but, at other times, a single melody line that needed fanning back out into an ensemble piece. I discuss some of the questions that this process at times threw at us on the Performing Practices page.

We hope we have produced a set of arrangements that you, our readers, can download to play for dance or to study the repertoire; you may find that you need to alter the arrangements to suit your own ensemble’s instrumentation and we hope that the arrangements will give you plenty of inspiration and insight into how to do this. Finally, we hope to have produced a set of recordings that can be used for dancing and to study dance repertoire around 1800. For the most part, we used historical instruments in our recordings to give a sense of the timbral qualities that the music once had and to allow us to experiment with instrumental balance as explained in the page on performing practices. For practical reasons – both for us and for users of this material – we used a modern harp in some instances as this is surely easier to come by for many dancers and musicians interested in this repertoire today. The harp also presents the biggest challenge in transferring repertoire written for early nineteenth-century instruments to their modern grandchildren and in the case of one set of dances, the Yorkshire Hussars Quadrilles we therefore experimented with different versions.

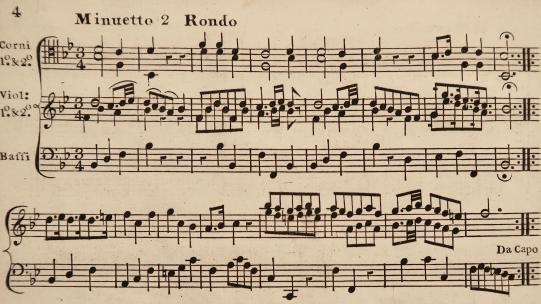

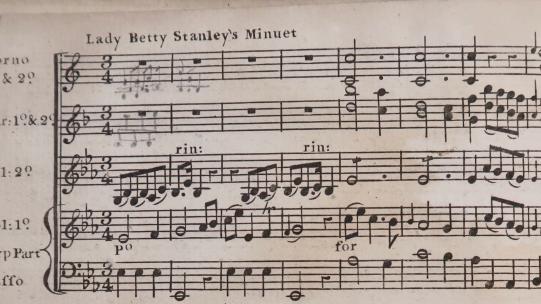

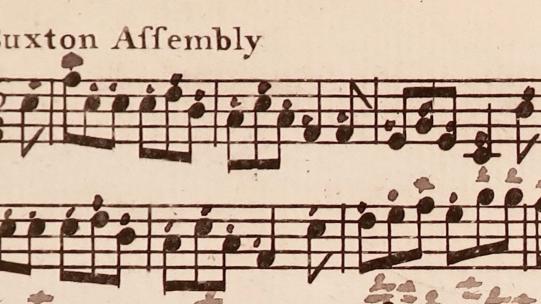

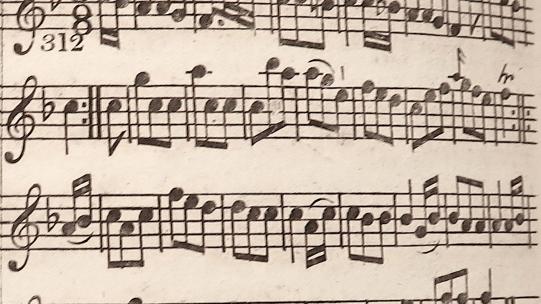

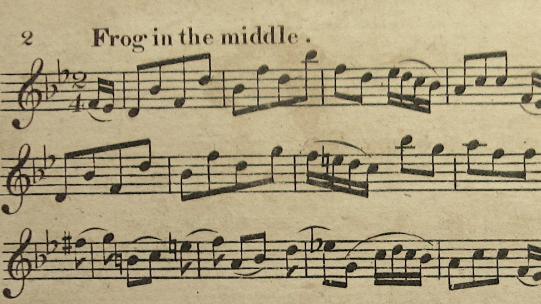

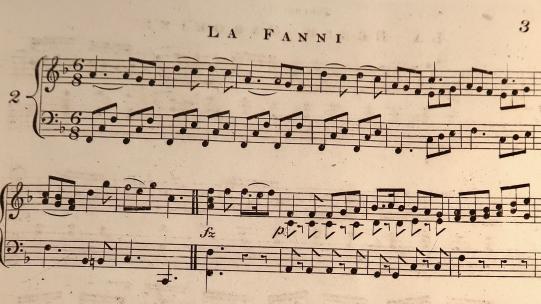

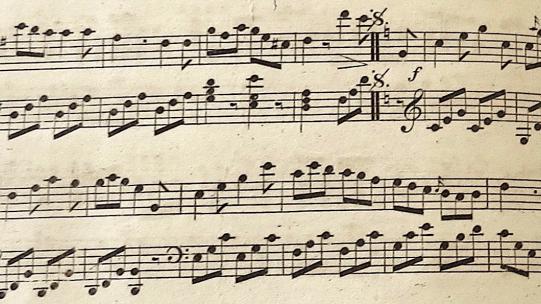

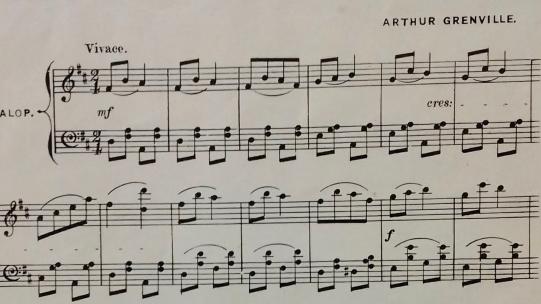

Below you will find the scores, parts and recordings for numerous dances hidden behind 13 score images. The pages beyond each image also include further information on the individual dances and the material we used to make the arrangements. All files - scores, parts and recordings - can be downloaded and are in the public domain, free for anyone to use. Please respect the credit requests. Enjoy!