Arrangements: Bringing the Theatre to the Dance Floor

The almost insatiable demand for new dance music not only fostered the supply of original compositions but also prompted a flood of arrangements from other genres. Quadrille music was particularly suited to absorbing theatrical extracts and illustrates the flexibility that existed between the stage and the ballroom in the early to mid-nineteenth century.

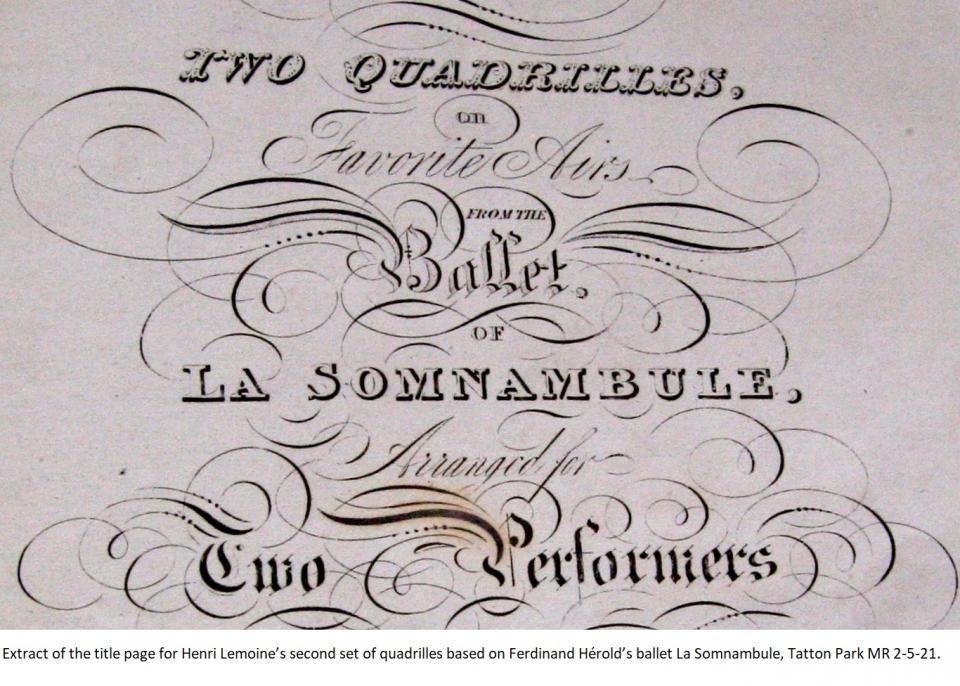

Considerable quantities of music from opera, ballet and melodrama were plucked from their original settings and rearranged into sets of quadrilles. On the surface, these arrangements catered for simplicity and often paid little regard to the musical chronology of the original work. They prompted significant discomfort in French musical criticism in the early 1830s due to their perceived degradation of taste, association with amateur female performers, and the threat they posed to artistic integrity. Sometimes the publications predated the arrival of a particular production in the theatre, meaning that audiences learned about it through their feet before they saw it on stage (Clark 2002).

Considerable quantities of music from opera, ballet and melodrama were plucked from their original settings and rearranged into sets of quadrilles. On the surface, these arrangements catered for simplicity and often paid little regard to the musical chronology of the original work. They prompted significant discomfort in French musical criticism in the early 1830s due to their perceived degradation of taste, association with amateur female performers, and the threat they posed to artistic integrity. Sometimes the publications predated the arrival of a particular production in the theatre, meaning that audiences learned about it through their feet before they saw it on stage (Clark 2002).

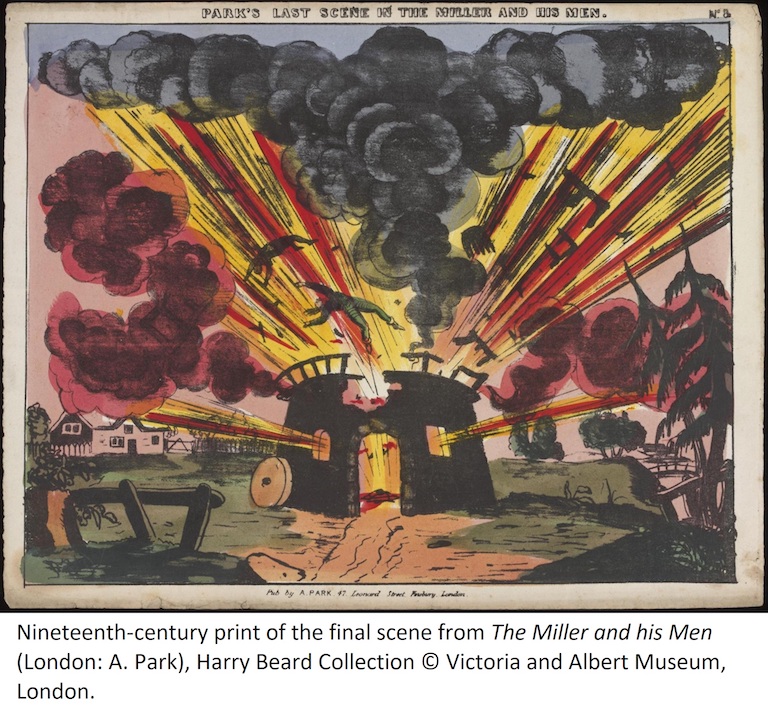

In Britain, local provincial musicians adapted such theatrical music for their own purposes. A glance at music performed at the York Winter Assemblies provides a snapshot of what music was used and how these arrangements were perceived. On 30 January 1819, the York Herald reported on the fourth Winter Assembly, announcing that “the Music (which has been arranged solely for these Balls) is far superior to any we have yet heard – the selection for the third and fourth sets of Quadrilles is we think peculiarly happy – an air from the Melo Drama of The Miller and his Men, and that of Viva Enrico, excited much notice and admiration”. The two works occupied different ends of London’s theatrical spectrum: Viva Enrico is possibly from Vincenzo Pucitta’s heroicomic opera La Caccia di Enrico IV, which appeared at the King’s Theatre in 1809, featuring the operatic superstar Angelica Catalani, while Sir Henry Rowley Bishop’s The Miller and his Men, which premiered at Covent Garden in 1813, exemplified a genre that relied on overt theatrical craft and an appeal that extended down the social class ladder (Fenner 1994).

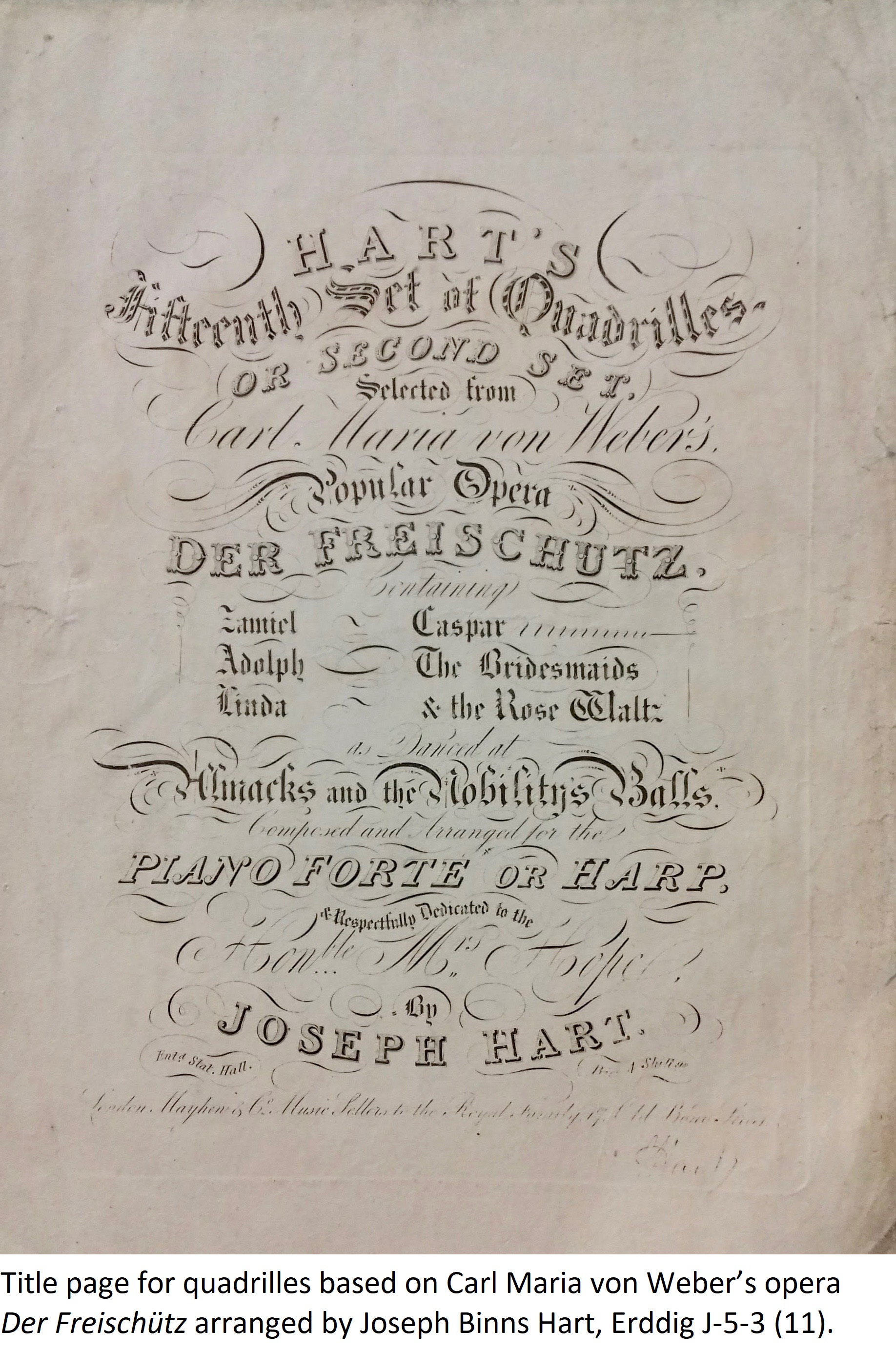

The choice of music for these sets of quadrilles likely lay with William Hardman, leader of the band for the York Winter Assemblies, which subsequently became known as the York Quadrille band. The piano arrangement of the quadrilles was carried out by Philip Knapton (York Herald 6 March 1819), a composer and music publisher whose business Hardman was later to take on. Such arrangements were common in the nineteenth century and were often attributed on title pages to band leaders such as Joseph Binns Hart and Philippe Musard. Knapton’s publication, however, raises questions about how much of the dance music produced for the domestic market was arranged by publishers or copyists, and what the collaborative processes were that existed between publishers and dance band leaders, especially in the case of someone like Knapton who was also a pianist, violinist and composer in his own right (Griffiths n.d.).

The choice of music for these sets of quadrilles likely lay with William Hardman, leader of the band for the York Winter Assemblies, which subsequently became known as the York Quadrille band. The piano arrangement of the quadrilles was carried out by Philip Knapton (York Herald 6 March 1819), a composer and music publisher whose business Hardman was later to take on. Such arrangements were common in the nineteenth century and were often attributed on title pages to band leaders such as Joseph Binns Hart and Philippe Musard. Knapton’s publication, however, raises questions about how much of the dance music produced for the domestic market was arranged by publishers or copyists, and what the collaborative processes were that existed between publishers and dance band leaders, especially in the case of someone like Knapton who was also a pianist, violinist and composer in his own right (Griffiths n.d.).

![‘The Celebrated Bacchanalian Song from Der Frieschütz’ [sic], image after George Cruikshank (London: 1826) © The Trustees of the British Museum. This music is used as the basis for the 4th quadrille in The York Quadrilles. A [7th] Set of Quadrilles, As Performed at the York Winter Assemblies (London: Chappell & Co.; Goulding & Co.; W. Bainbridge. York: Knapton White & Knapton, [1825?]). ‘The Celebrated Bacchanalian Song from Der Frieschütz’ [sic], image after George Cruikshank (London: 1826) © The Trustees of the British Museum. This music is used as the basis for the 4th quadrille in The York Quadrilles. A [7th] Set of Quadrilles, As Performed at the York Winter Assemblies (London: Chappell & Co.; Goulding & Co.; W. Bainbridge. York: Knapton White & Knapton, [1825?]).](/sites/sound-heritage.soton.ac.uk/files/filefield_paths/der_freischutz_bacchanalian_song_-_british_museum.wc_.jpg)

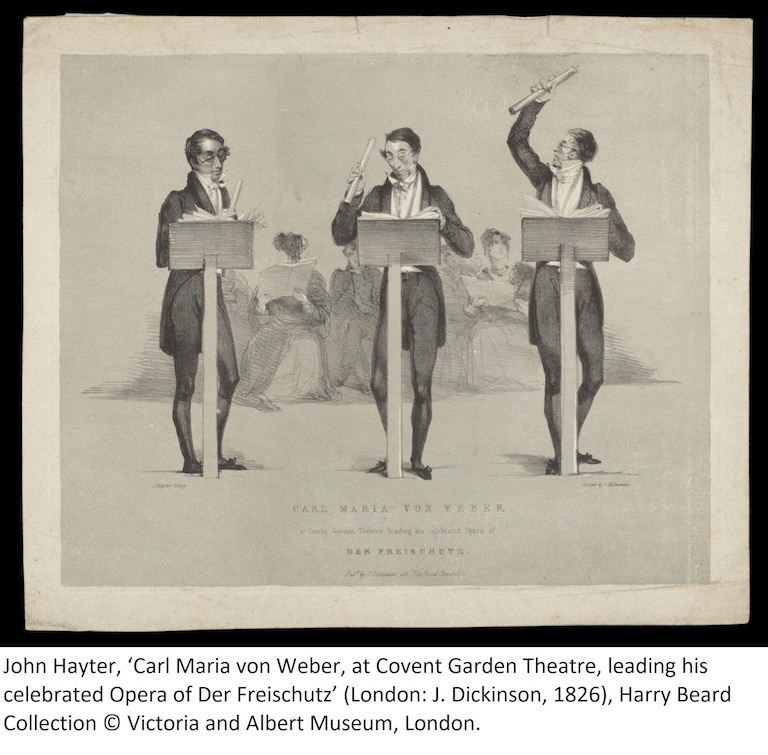

Six years later, another set of quadrilles performed at the York Winter Assemblies yoked themselves to one of the most popular German operas of the time. In the summer of 1824, Carl Maria von Weber’s Der Freischütz (1821) landed on the English stage, albeit in an adapted version, and stormed into British musical consciousness. It was so successful that it spawned multiple adaptations and indelibly changed London’s theatrical landscape; its cultural saturation would have made it almost impossible to avoid, especially in excerpted form. It displayed some kinship with melodrama, and indeed Bishop was responsible for arranging Weber’s music for the belated production of Der Freischütz at Drury Lane (Fuhrmann 2015). By January 1825 Hardman’s band was playing quadrilles based on Der Freischütz and two months later the Knapton firm had produced a published version, advertised on the same day that Der Freischütz was due to show at the Theatre Royal in York (York Herald 19 March 1825).

The introduction of the Freischütz quadrilles prompted the Yorkshire Gazette (8 January 1825) to pen an extended commentary on the practice of arranging opera into quadrilles. The principal complaint was the perceived mismatch between the emotional quality of the opera’s story and the emotional territory occupied by the quadrille: “The fashion which now prevails of arranging Selections from Operas for Quadrilles, has, we think, in this instance, been carried too far; something more than novelty is wanted: Weber’s music is grand and powerful, and in the opera which keeps so long possession of the London stage, with the assistance of its wild and romantic story, is remarkably attractive, but its character is totally unsuited to the easy, elegant, gay, seductive quadrille”. Many composers and arrangers evidently thought otherwise, judging by the number of quadrilles produced from the opera. Indeed, the musical repetition that the quadrille engendered as a form virtually ensured any memorable melody would become lodged in consciousness.

The reviewer went on to indicate that further selections from Rossini, Mozart, Cimarosa, Paer, Kozeluch and Bishop “will bear a constant repetition” and thus by implication were more acceptable. Several of these composers were well-known for their contribution to comic opera and it is possible that a distinction was being drawn along such lines. Although it is unfortunate that further expansion of these composers’ works was not given, the list at least indicates the contemporary flavour of music from which Hardman and Knapton drew their selections. The continental influence is notable, though by no means unexpected. Knapton had taken over the running of subscription concerts in York with John Camidge (Griffiths n.d.) and in the year before the Freischütz quadrilles were published they featured works by Paer, Mozart, Rossini, Bishop, Pucitta and Weber, particularly at Knapton’s own benefit concert which included excerpts from Der Freischütz (Yorkshire Gazette 6 and 13 March 1824). Both the concerts and the winter assemblies were held in York’s assembly rooms, and the concerts often concluded with a ball. Given the close proximity in which concerted music and dance took place, it is not difficult to see how the music could also bleed from one to the other.

Further Reading:

Clark, Maribeth. 2002. “The Quadrille as Embodied Musical Experience in 19th-Century Paris.” The Journal of Musicology 19, no. 3 (Summer): 503-526.

Fenner, Theodore. 1994. Opera in London: Views of the Press 1785-1830. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press.

Fuhrmann, Christina. 2015. Foreign Opera at the London Playhouses: From Mozart to Bellini. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Griffiths, David. n.d. A Musical Place of the First Quality: A History of Institutional Music-Making in York c.1550-1990. York: The York Settlement Trust.