Pedagogy: Dance in a Commercial World

Discourses on dance in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries recognised its value in promoting physical health, but also its deep attachment to concepts of genteel behaviour, moral probity and display. Key to this attachment was an emphasis on quality of movement: refined and graceful deportment was a marker of polite education and privilege, achieved by disciplining and moulding the body through dance as well as the use of mechanical devices. Dance was an important tool in developing the performance of gentility and helped to facilitate everyday social intercourse among the upper classes (Bloomfield and Watts 2008; Tardif 2002). Instruction in dance was indelibly linked to the ability to perform myriad polite social gestures; as Francis Mason observed, “In the common intercourse of life, nothing tends more than general deportment to impress a sense of superiority and refinement on society, and it is impossible to disconnect its cultivation from dancing, with which it is so intimately associated” (Mason 1854, 5-6). In addition to shaping external appearances, a cultivated deportment also reflected inner character and rectitude, yoking the physical body to qualities of mind and acting as a counterfoil to sections of society which questioned the morality of dance. Bringing the body under deliberate physical control therefore had the potential to stimulate and propagate approved conduct on a communal level, and protect against a perceived descent into savagery (Henderson 1850?; Leppert 1988; Webster 1851).

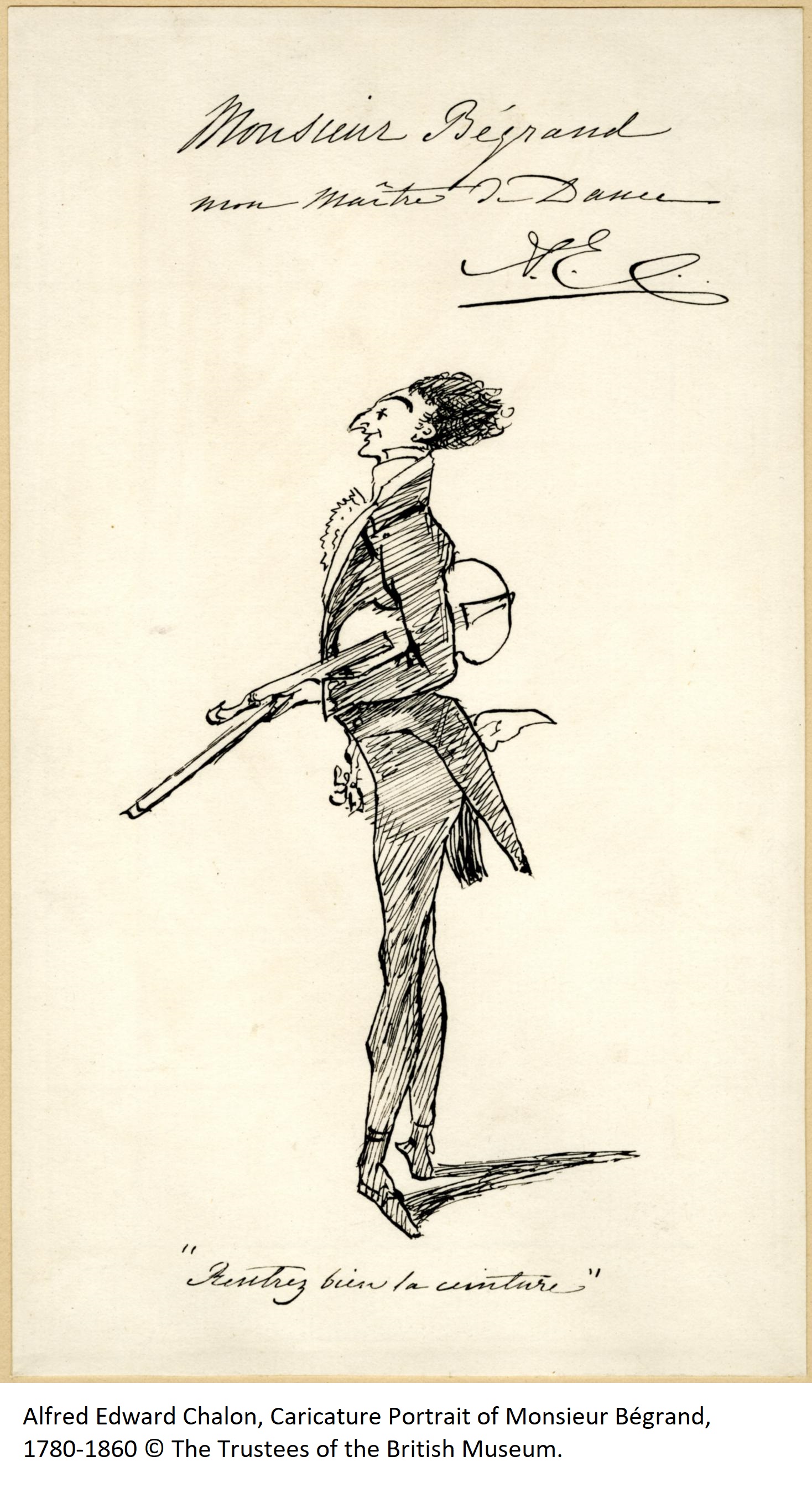

Dancing masters and mistresses were instrumental in maintaining these ideologies. Indeed, they were lynchpins in Georgian Britain’s social and cultural life. Dance’s popularity as a pastime and as a tool for acquiring and demonstrating status catapulted dancing masters to a position of power: they presided over the consumption of leisure while also maintaining and reinforcing social structures. As pedagogues, dancers, choreographers, authors and musicians, teachers of dance were multi-skilled professionals who engaged in the commerce of bodily display. Through a commercial lens, deportment could be regarded as a commodity that was purchased, traded and displayed on a near daily basis, with dance teachers contributing in multiple ways to its dissemination: they provided lessons in private homes, academies and schools; hosted balls for their pupils to showcase their achievements; and acted as masters of ceremonies, while some additionally forged theatrical careers. They were patronised by those who could afford to hire them, purchase their publications, and watch them perform. Despite their indispensability, dancing masters also inhabited a questionable moral space: many were foreigners which, coupled with theatrical connections, sat uneasily with British notions of decorum and purity, leading to denigration, mockery and ridicule (Bloomfield and Watts 2008; Leppert 1988; Tardif 2002).

Dancing masters and mistresses were instrumental in maintaining these ideologies. Indeed, they were lynchpins in Georgian Britain’s social and cultural life. Dance’s popularity as a pastime and as a tool for acquiring and demonstrating status catapulted dancing masters to a position of power: they presided over the consumption of leisure while also maintaining and reinforcing social structures. As pedagogues, dancers, choreographers, authors and musicians, teachers of dance were multi-skilled professionals who engaged in the commerce of bodily display. Through a commercial lens, deportment could be regarded as a commodity that was purchased, traded and displayed on a near daily basis, with dance teachers contributing in multiple ways to its dissemination: they provided lessons in private homes, academies and schools; hosted balls for their pupils to showcase their achievements; and acted as masters of ceremonies, while some additionally forged theatrical careers. They were patronised by those who could afford to hire them, purchase their publications, and watch them perform. Despite their indispensability, dancing masters also inhabited a questionable moral space: many were foreigners which, coupled with theatrical connections, sat uneasily with British notions of decorum and purity, leading to denigration, mockery and ridicule (Bloomfield and Watts 2008; Leppert 1988; Tardif 2002).

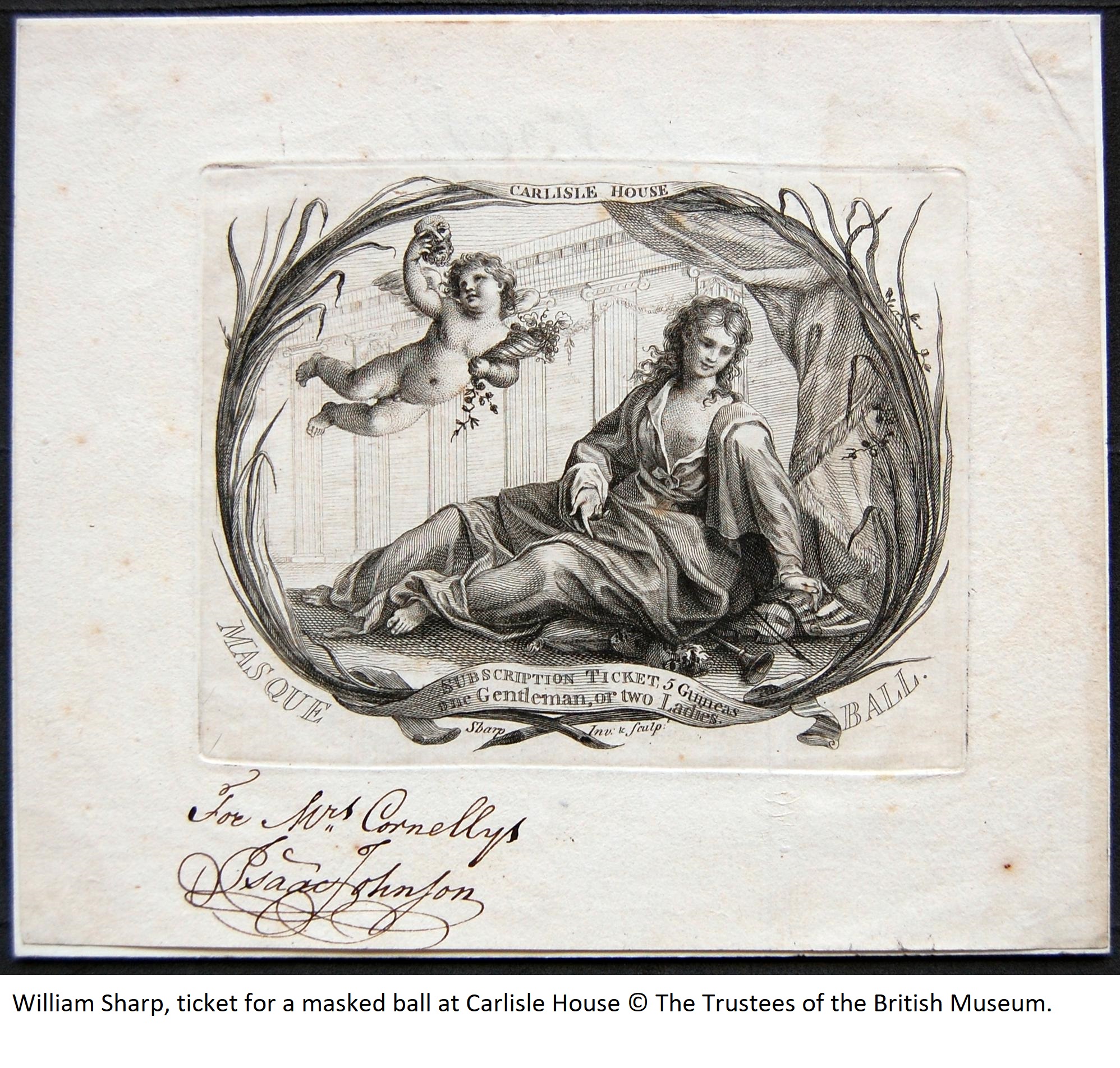

The business of dance pedagogy can be seen through the career of Giovanni Battista Gherardi. Employed as a dancer and ballet master at the King’s Theatre in the early 1760s after a declared career at the Paris Opéra, Gherardi was also engaged in teaching, both for the stage and for social dance (Highfill Jr., Burnim and Langhans 1978). Drawing on increasing public interest in the cotillion, by 1770 Gherardi had published three books of cotillions and set up a cotillion academy. The academy was publicised in an advertisement for his second set of cotillions as an outgrowth of his teaching method, which the cotillion publication reportedly exemplified (Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser 15 February 1769). Gherardi made no bones about his target audience, declaring in the introductory material that the academy was to serve “the Nobility and Gentry, admirers of these fashionable performances”; its operation by subscription “wholly confin’d to Ladies & Gentlemen of Rank, Fashion, & Fortune” defined it as an exclusive enterprise (Goff 2014). By the early 1770s Gherardi was also hosting balls which served to further advertise his publications and his professional standing as a pedagogue. In advance of a forthcoming ball at Carlisle House in Soho Square, previously home to sumptuous entertainments hosted by Theresa Cornelys, Gherardi announced that a range of dances “composed by him for the Use of his Scholars” would be performed; the event would also include cotillions “taken from the four Books of Mr. Gherardi’s composition, and danced after the Manner of the Academy, held every Saturday at his House in Rathbone place, for the Purpose of Ladies and Gentlemen practising these polite and fashionable Dances” (Public Advertiser 22 February 1774). Gherardi’s ball was both an exhibition of his teaching skills and an embodied advertisement of his publications.

Gherardi’s use of display dancing was pushed into the realm of theatrical representation in his third book of cotillions. In a lengthy dedication to Lady Bridgeman of Weston Park, Gherardi noted that he specifically included two dances in the collection in honour of the Bridgeman family’s production of Charles Dibdin’s comic opera, The Padlock. Furthermore, he praised the performance of his pupils, the Bridgeman children, in the allemandes and “Dances I composed for them on the occasion” (Gherardi 1770). Two months prior to the staging of The Padlock, Gherardi hosted a ball in which his pupils performed a variety of dances that were directly linked to his publications; they not only included his books of cotillions but also “several kinds of Allemandes, particularly that spoken of in Mr. Gherardi’s collection of Minuets, &c. published the present winter” (Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser 7 March 1770). A copy of Gherardi’s Twelve New Allemandes and Twelve New Minuets [1769] is located in the music collection at Weston Park and although lacking ownership details, it is highly likely that the allemandes Gherardi referred to in relation to The Padlock came from this publication. The private production of The Padlock, after which Gherardi received several “handsome Compliments” from aristocratic members of the audience, functioned as a display of his skill and was no small advertisement for his expertise, knitting together existing dances and publications, and yielding the promise of new ones.

Gherardi’s use of display dancing was pushed into the realm of theatrical representation in his third book of cotillions. In a lengthy dedication to Lady Bridgeman of Weston Park, Gherardi noted that he specifically included two dances in the collection in honour of the Bridgeman family’s production of Charles Dibdin’s comic opera, The Padlock. Furthermore, he praised the performance of his pupils, the Bridgeman children, in the allemandes and “Dances I composed for them on the occasion” (Gherardi 1770). Two months prior to the staging of The Padlock, Gherardi hosted a ball in which his pupils performed a variety of dances that were directly linked to his publications; they not only included his books of cotillions but also “several kinds of Allemandes, particularly that spoken of in Mr. Gherardi’s collection of Minuets, &c. published the present winter” (Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser 7 March 1770). A copy of Gherardi’s Twelve New Allemandes and Twelve New Minuets [1769] is located in the music collection at Weston Park and although lacking ownership details, it is highly likely that the allemandes Gherardi referred to in relation to The Padlock came from this publication. The private production of The Padlock, after which Gherardi received several “handsome Compliments” from aristocratic members of the audience, functioned as a display of his skill and was no small advertisement for his expertise, knitting together existing dances and publications, and yielding the promise of new ones.

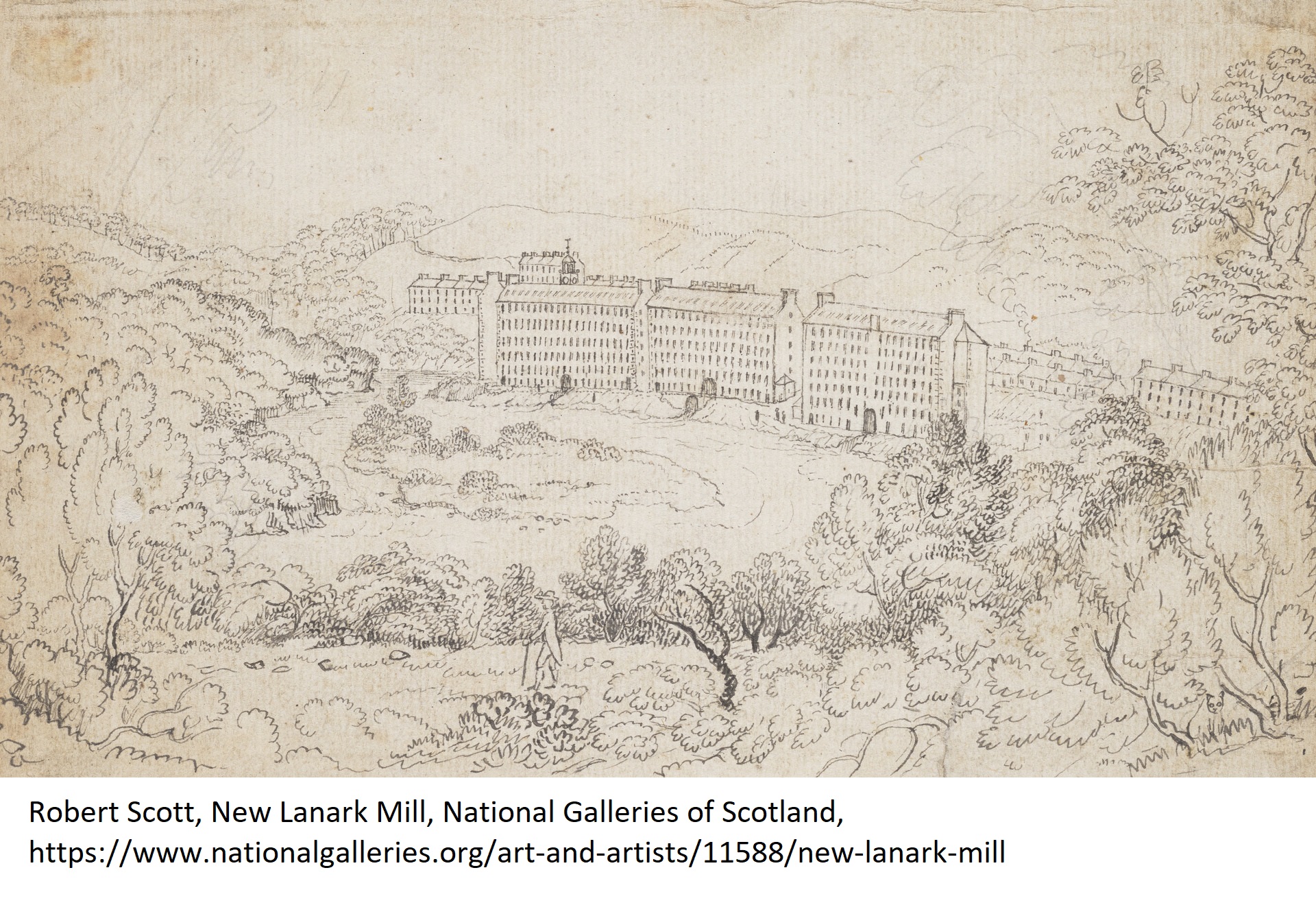

If such activities typified how dance was employed to shape individual bodies and the collective experiences of the elite, the incorporation of dance into the educational curriculum of Robert Owen was nothing less than a strategy for producing a new world vision. Owen was manager and part-owner of cotton mills at New Lanark after taking over from his father-in-law in 1800. During his tenure, he turned the mill community into a utopian social experiment. He sought to ameliorate misery (particularly in the poor and working classes) and produce a happy and harmonious society on an inter-generational scale through a system whose benefits were conceived to spread from New Lanark to create global reform. By his own account, the community at New Lanark was cobbled together and lived in a wretched state of poverty, profligacy and crime (Owen 1817b). Perhaps unsurprisingly, Owen articulated his desire “to effect a complete and thorough improvement in the internal as well as external character of the whole village” when he opened his Institution for the Formation of Character in 1816 (Owen 1817a, 13). Owen’s premise was that character was formed through education and circumstances, and that children’s characters were particularly pliable; accordingly, he provided education for infants through to adult workers, to mould from earliest childhood and retrain previously acquired ignorance. His approach favoured a rational education infused with charity and kindness, designed to promote happiness within the individual and community. Within this framework, he also recognised the need for bodily health, and the role that leisure and recreation could play in maintaining personal and communal wellbeing, and in promoting virtuous conduct amongst his workers (Davidson 2010; O’Hagan 2011; Owen 1817b).

Dance and music were employed at New Lanark amongst both children and adults to contribute towards Owen’s overarching aims. While dance was explicitly linked to improving deportment, both disciplines served the ideology of “moral refinement” on the principle that righteous behaviour was best achieved through collective happiness (Dale Owen 1824; Davidson 2010; May, Kaur and Prochner 2016). The children received dance instruction from David Budge, who was also responsible for musical tuition and apparently plied a trade as a painter and glazier; his importance within the curriculum was emphasised by the parity of pay he shared with more academic teachers (Browning 1971; Dale Owen 1824; Davidson 2010). Dancing took place in the purpose-built “New Institution” designed to support the community in developing new habits of character. A multi-purpose room, equipped with a musicians’ gallery and featuring zoological, mineralogical and geographical décor, catered for lectures, dancing and singing lessons, and balls (Dale Owen 1824; May, Kaur and Prochner 2016). As boys and girls received academic instruction largely separately, dance and music were important as combined communal activities. The adult workforce was encouraged to dance after hours, with dancing scheduled alternately with evening lectures (Davidson 2010). Owen’s wasn’t the only factory to incorporate a ballroom and the trend for organised dance in factories would proliferate in the following century (Chance 2017). Owen’s establishment attracted significant numbers of visitors and it is clear that exhibitions of dance and music were key to how the Institution was presented publicly (Siméon 2017). Indeed, one newspaper declared in 1833, well after Robert Owen had left New Lanark, that “Scarcely a day passes, but parties in carriages and gigs…are shown through the Mills, Schools, &c. the great attraction of which is allowed on all hands to be the excellent method of teaching singing and dancing practised by Mr Budge” (Caledonian Mercury 19 September 1833). Visitor descriptions of such displays contained broad similarities and give the sense that they were choreographed, performative and even voyeuristic acts not dissimilar to exhibitions of dance in well-regarded boarding schools, particularly as they sometimes incorporated drill manoeuvres. Although the quality of dancing differed between accounts, the children were largely highly commended, exhibiting grace and skill despite many of them dancing barefoot. Such a scenario is depicted in George Hunt’s portrait of Owen’s Institution, showing numerous spectators sitting on benches around the room observing the children’s dancing (Davidson 2010; May, Kaur and Prochner 2016).

Despite Owen’s apparent benevolent intentions, his commercial instincts were not far from the surface. In the address fronting his third essay in A New View of Society, he explicitly addressed manufacturers and referred to workers variously as living machines, mechanisms and instruments. He detailed how they could be “easily trained and directed to procure a large increase of pecuniary gain” whilst imparting “high and substantial gratification” upon the owner. In dehumanising terms – unnamed and simply relegated to ‘it’ – he regarded the “living mechanism” as something which could be improved “by being trained to strength and activity”, a workforce utilised “as an instrument for the creation of wealth” (Owen 1817b, 73-76). In this context, the maintenance of healthy bodies through dance was not just in aid of the workers’ own happiness, but was strongly linked to economic prosperity and the pleasure of the owner; this was particularly so given that exhibitions of dance at New Lanark had taken on a starring role, serving simultaneously as a visible indicator of Owen’s successful moulding programme and as entertainment (Siméon 2017). Writing in 1819, the poet Robert Southey was scathing of Owen’s approach: he drew similarities between the children’s drilling and the synchronised enforced wagging of cows’ tails through mechanised means, and equated his ideology with the institution of slavery and the deployment of absolute power (Southey 1929).

Owen’s manufactured control of his population tapped into the language of bodily discipline so pervasive in dance literature. The acquirement of a graceful and easy deportment required controlled and practised use of the body; dance moulded a person’s physique into an artificial ideal and rectified deviant motions. Owen’s focus on training and regulation (even of enjoyment), and the collective conformity he sought to achieve through physical drills and the inculcation of moral character, applied these concepts at a communal level. His focus on the malleability of children and their development from the youngest age reflected a centuries old concern for moulding children’s bodies into a proper (and straight) form (May, Kaur and Prochner 2016; O’Hagan 2011; Vigarello 1989). Whilst Owen’s appropriation of the existing discourse on dance for the lower classes formed part of his stated aim to “raise all classes without lowering any one”, it also helped to facilitate a collective docility and subservience which aided his business (Butt 1971; Dale Owen 1824, 76; Davidson 2010). While dancing masters such as Gherardi attempted to create “controlled, developed and privileged performance” in the service of gentility (Vigarello 1989, 179), Owen’s employment of dance, delivered in part via Budge, created a different kind of performance: the spectatorship turned from commodification of the body as an expression of status, to commodification of multiple bodies for the purposes of industrialisation.